Against tough odds, Bering Strait residents seek cross-border ocean protections

Technology and better cross-border cooperation promise a safer, cleaner Bering Strait. But Russia's invasion of Ukraine is complicating that.

When waves of trash began piling up on beaches on the Alaska side of the Bering Strait, residents looked west to the Russian side for the culprit. That was logical: Of those items with any kind of labeling, the majority had writing that was in the Russian language.

Some items were benign, like a Russian sailor’s cap. But some were worrisome, like canisters that held solvents or insecticide.

The likeliest explanation is that the trash — which arrived in the summer of 2020 and resumed last summer — was from increased Russian ship activity in a sea that is losing its long-term ice cover, said a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report issued late last year.

The precise source of the debris still remains a mystery, said Peter Murphy, Alaska coordinator for the NOAA’s marine debris program. No one ever took responsibility, despite many overtures to Russia about the threats to shared natural resources, Murphy said.

“The animals, the currents don’t care about the border,” he said.

The piles of marine debris are reminders that in the Bering Strait region, what happens in Russia doesn’t stay in Russia.

The two sides of the border comprise a single marine habitat on which fish, mammals, birds and people rely. And on both sides of the border, drastic change is underway in that habitat, showing up in ice loss, water quality, algal blooms, die-offs of birds and mammals, fish populations in new areas.

Protection of that shared habitat starts with shared knowledge — much of which depends on transboundary cooperation that is now in doubt because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The seven other Arctic nations have paused all work of the eight-nation Arctic Council, which Russia currently chairs. Prospects for Bering Strait scientific and environmental cooperation — which dates back to the Soviet era — are now dimming.

“All bilateral and multilateral efforts within the Arctic region involving Russia, from the Arctic Council to the Arctic Coast Guard Forum to regional scientific and maritime transportation agreements may be in jeopardy,” warned Arctic experts at the Wilson Center, a Washington-based think tank. “The largescale invasion of Ukraine is such a serious step for all States active in the Arctic that normal modes of cooperation, including those focused on climate change, will likely be reassessed,” the experts’ statement said.

How technology can help

Against those odds, Bering Strait residents, scientists and resource managers are seeking to fill in knowledge gaps so they can better protect the region.

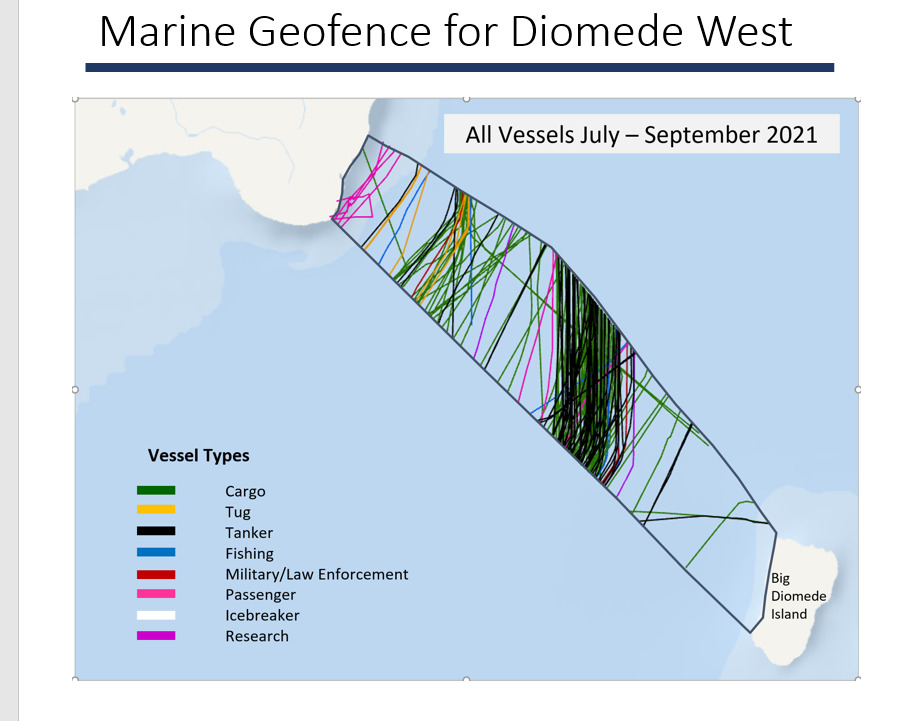

On Little Diomede, the tiny Alaska island in the middle of the Bering Strait, villagers keen to learn more about the volume and type of ship traffic passing through have turned to a new technological tool: geofencing.

Geofencing technology allows users to track vessels in specified marine zones and, if necessary, communicate with vessel operators to notify them about dangers or rule violations. In Alaska, geofencing technology is provided through a partnership of organizations in government agencies, the University of Alaska, nonprofits and industry.

A geofencing system set up last summer proved enlightening to residents of Diomede, a village of about 100 that is less than 3 miles east of Russia’s Big Diomede Island.

The system records traffic on both sides of the island, and the volume has been surprising, said Opik Ahkinga, environmental coordinator for the Native Village of Diomede, the tribal government.

“I get emails all the time,” she said.

That new knowledge raises some important questions. Ahkinga has particular worries about marine noise, something that is drawing new attention as Arctic ship traffic increases.

“How is this disturbing the mammals that use our Bering Strait? Because we are a major highway for migration,” she said. Whales, for example, need to communicate to each other through calls, but the noise issues go beyond that and could even affect fish movements, she said. “The mammals are going to go and find food,” she said. “But where is the food going?”

Statistics confirm that Bering Strait ship traffic has increased.

Bering Strait transits totaled 262 in 2009; by 2021, that total reached 555, according to the World Wildlife Fund and the Marine Exchange of Alaska. As of last year, those transits have been happening even in winter, with tankers carrying liquefied natural gas from Russia’s Yamal Peninsula along Russia’s Northern Sea Route and through the strait to Asian markets.

Traffic from Russia is expected to continue growing, led by the expanding LNG trade, which already accounts for about two-thirds of the cargo shipped through the Northern Sea Route, according to Alexey Knizhnikov, a program manager for the World Wildlife Fund in Russia.

By 2024, 80 million tons of cargo is expected to be shipped through the Northern Sea Route, Knizhnikov said in a presentation to the Alaska Forum on the Environment, a conference held online in February — before the Ukraine invasion. “This is really huge,” he said. “This brings additional difficulties for safety in terms of environment safety shipping safety and human-being safety.”

Ship activity is on the rise on the Alaska side, too, as are the concerns about impacts.

There are big cod catcher-processing vessels that have sailed north to the Bering Strait region to target fish stocks that are shifting north. There is cruise ship traffic that — despite an interruption forced by the COVID-19 pandemic — appears headed for more activity starting this summer. Eleven different cruise ships are scheduled for a total of 21 port calls at Nome this year, according to the Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska.

Mining is also driving a lot of the traffic — from vessels floating just offshore from Nome and dredging the seafloor to supply ships carrying gravel extracted from a quarry near Nome to ships servicing mining projects in exploration and development phases, including a graphite mine project planned for Port Clarence, where some port infrastructure has been proposed. A Nome port expansion project just got a boost of $250 million in federal funds.

Feelings about ship traffic and port development are mixed in the Bering Strait region. Some welcome the potential economic boon, while others worry about the myriad impacts.

“We like to hunt here, and that should be the first priority, fishing and hunting, the stuff that we do locally,” said Blanche Okbaok-Garnie, mayor of Teller, one of two villages adjacent to Port Clarence.

Success stories

Amid these concerns, there have been some safety successes.

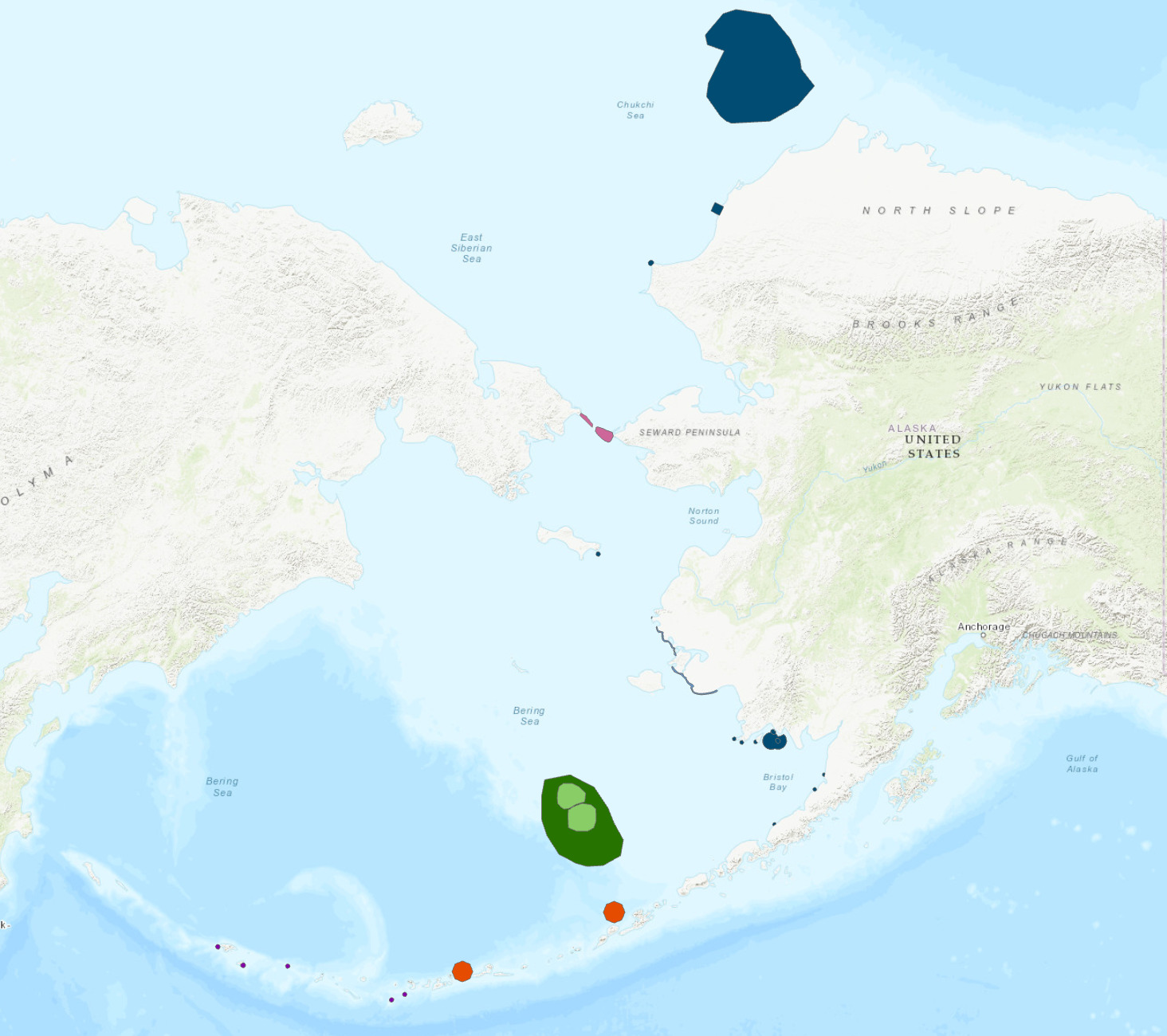

Geofencing has proved useful in other waters off Alaska, helping keep track of traffic and, when necessary, enforcing rules about no-go areas. Geofencing projects extend from the Aleutian Islands in the south to the Chukchi Sea, said Aaron Poe, coordinator of the Aleutians and Bering Sea Initiative. The organization, which has its roots in an Obama administration program within the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has helped bring geofencing technology to important western and northern Alaska marine sites.

One of those hotspots in that region is the Hanna Shoal, a key biological area in the Chukchi Sea where the U.S. Geological Survey requested geofencing coverage, Poe said. In 2021, the system tracked 81 vessels going through that shallow-water area, an ultra-productive area and preferred food-foraging site for walruses, seabirds and other marine life.

Another project using technology is seeking to replicate for the Bering Strait a transboundary version of the ecological database used to identify and protect vulnerable U.S. marine areas. The Environmental Response Management Application has been used by NOAA for oil-spill and disaster planning and response, but for national security reasons, it has never been open to officials from Russia or other countries.

Now the Alaska Ocean Observatory System and the WWF have teamed up to develop a Bering Strait-specific ERMA-type system that could be shared internationally. The Bering Strait Transboundary Incident Response Tool, AOOS and WWF representatives said, would be put to use next year during an in-person on-the-water disaster exercise that was planned by the U.S. Coast Guard and its Russian counterpart, the Marine Rescue Service — though plans for that exercise are now uncertain.

The agencies were able to gather six months ago in Anchorage for a tabletop exercise. Last February, Russia and the U.S. signed an agreement that updates and strengthens a joint contingency plan first created in 1989, in the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, a time before the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

U.S.-Russia cooperation produced a big victory for Bering Strait marine safety in 2018. That year, the International Maritime Organization approved Bering Strait-area shipping lanes and safety buffer areas proposed jointly by the U.S. and Russia.

One Coast Guard representative said he hopes that the longstanding Bering Strait ties will survive the Ukraine crisis.

“Here in the Coast Guard in Alaska, because we’re so close to Russia, because we share that maritime border, we have to have a working relationship in order to handle things,” Dan Seris, a waterways management with the Coast Guard, said during an online workshop held by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources. “It’s not gloom and doom. We find ways to communicate.”

Much more can be done in the future, bilaterally or otherwise, to boost Bering Strait safety, according to a new WWF report titled “Crossing the Line.”

Among the recommendations: establishment of speed limits for large ships, making a switch from use of heavy fuel oil to lighter fuels, enhancement of cross-border data-sharing and enactment of zero-discharge rules for travel in the strait.

At Diomede, residents have their own recommendations.

They want better training so they can be ready for the emergencies that are likely to happen as shipping increases, Ahkinga said. The community does have stockpiles of gear and equipment but lacks the type of training that has become standard in places farther south, as in the fishing communities of Prince William Sound.

“If it’s going to be an oil spill or if something happens out there, we’re going to need to respond,” she said.

A simple improvement, Ahkinga said, would be better communication from passing ships to avoid conflicts with hunters of other local people who might be on small boats. The Coast Guard does inform villages when their ships are coming, and that is a good habit to emulate, she said.

“The other ships do not notify the people. That would be a smart thing to do,” she said.

This story was supported by the Alaska Center for Excellence in Journalism and by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.