Scientists are trying to predict the impacts of this winter’s weird Arctic weather

With the most recent blast of exceptionally warm air into the Arctic at the end of last week, marking the third time this winter temperatures at the North Pole have approached the freezing point, scientists are increasingly seeking to understand what this will mean for the development of sea ice this winter and, then, what that might mean for the way the Arctic Ocean will behave this summer.

“The big concern this year is that changes in the Arctic are extending into the winter months,” Jeremy Mathis, the director of Arctic research for the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said earlier this week. “This means that the system isn’t getting the full reset that it normally gets even after the warm summers we’ve seen in the past.”

The warm air is also having an effect on the weather over land. Svalbard, for example, recorded the warmest temperature in all of Norway on February 7. The temperature, 4.1°C, was far from the highest ever recorded in Svalbard in February (7°C, in 2012). Temperatures rose further (to 5°C) as a high-pressure system situated over Finland pulled warm air over the territory, before falling back to normal, but the sudden warm wave comes after a 2016 that set records for both temperature and precipitation – although most of this fell as rain, rather than snow.

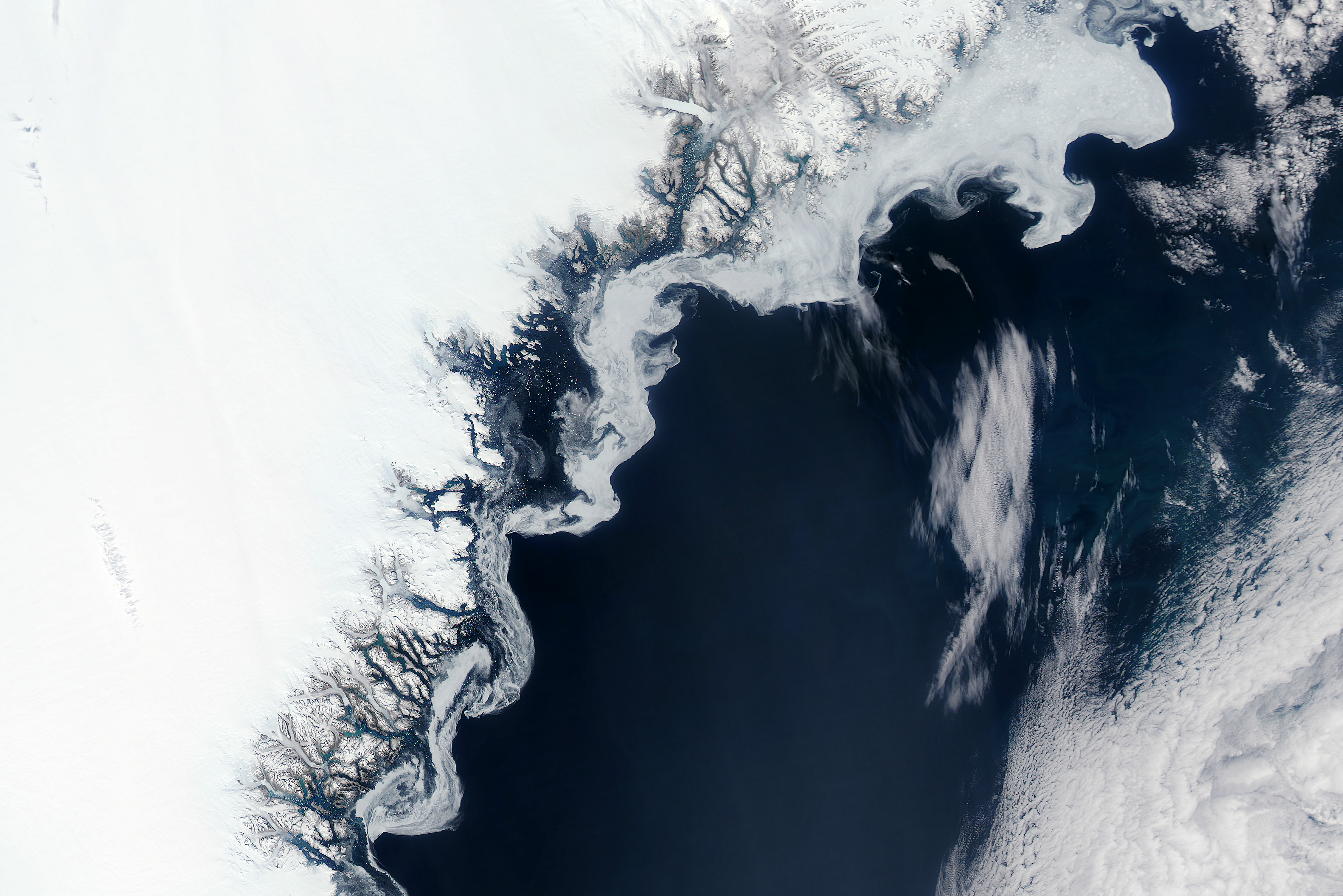

In Greenland, the warm air is also affecting the amount of snow falling, though in some areas, it has meant more, not less, accumulation.

According to Ruth Mottram, climatologist with DMI, the Danish meteorological office, since October, Greenland has seen a succession of major storms. These storms have dropped a lot more snow than average, particularly on the eastern coast and in the south.

“Warm air can hold more water vapour than cold air,” she wrote on Polar Portal, a climate website. “Projections from climate models suggest that as the atmosphere warms, there will also be increased snowfall over Greenland.”

The October storms pushed snowfall accumulations on the ice sheet far above what is normal for the time of year. Since December, however, the amount of snow falling over the ice sheet has followed a more normal pattern.

Northwestern Greenland, on the other hand, has had less snowfall than usual to date. This, according to Mottram, is because North Atlantic storms have been driving up the eastern coast, but northwestern Greenland has been relatively dry compared to the average.

Warm air also means more melting, though, and the question for scientists is whether one will balance the other out.

Regardless of whether the ice cap gains or loses mass this winter, she says it is more important to look at the development over an entire year or even longer, in order to get a true picture of what is happening.

As curious as this winter’s weather has been, she explains that, for scientists, the melting season – June, July and August – remain the most important.

“It is therefore still far too early to suggest that the Greenland ice sheet will not lose more mass than it gains this year.”

Unfortunately, according to Mottram, all projections for the future suggest that melt and runoff will dominate, leading to retreat of the ice sheet and sea level rise.