Federal move injects new life into Back River gold mine project

The Sabina Gold and Silver Corp. says they’re confident the Back River gold mine project will go ahead, now that Indigenous and Northern Affairs minister Carolyn Bennett has sent the project’s final hearing report back to the Nunavut Impact Review Board for more work.

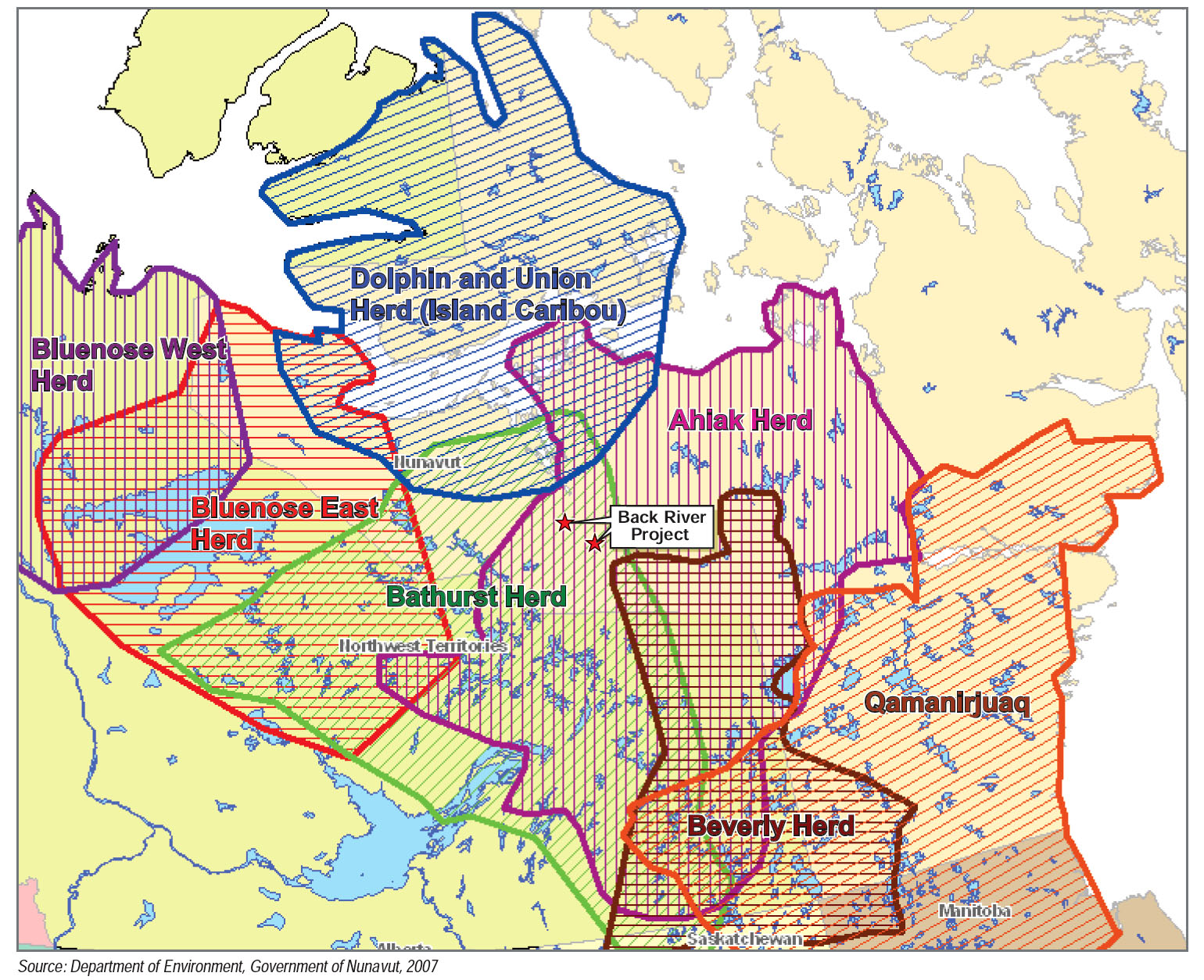

The NIRB recommended in June 2016 that the mining proposal not be approved, on the grounds that it could inflict damage on the region’s dwindling caribou herds that cannot be mitigated.

But Bennett and other federal ministers disagreed and said Jan. 12 that the NIRB did not fully explore last-minute caribou protection measures put forward by Sabina, the Kitikmeot Inuit Association and the Government of Nunavut.

And Bennett has instructed the NIRB to do more review work on the proposal, which could include more public hearings.

“We are extremely pleased that the minister has determined the NIRB should reconsider its recommendation regarding the project,” Sabina’s president and CEO Bruce McLeod said in a Jan. 13 release.

“We understand and support the NIRB’s desire for a high level of confidence in the mitigation and management proposed and believe that we have defined programs to address their issues.”

McLeod said the company is now awaits direction on the additional review process.

“Back River is aiming to be one of the next gold mines in Nunavut providing much desired jobs, training, infrastructure and economic opportunities to the territory with a best in class approach to protecting the environment,” he said.

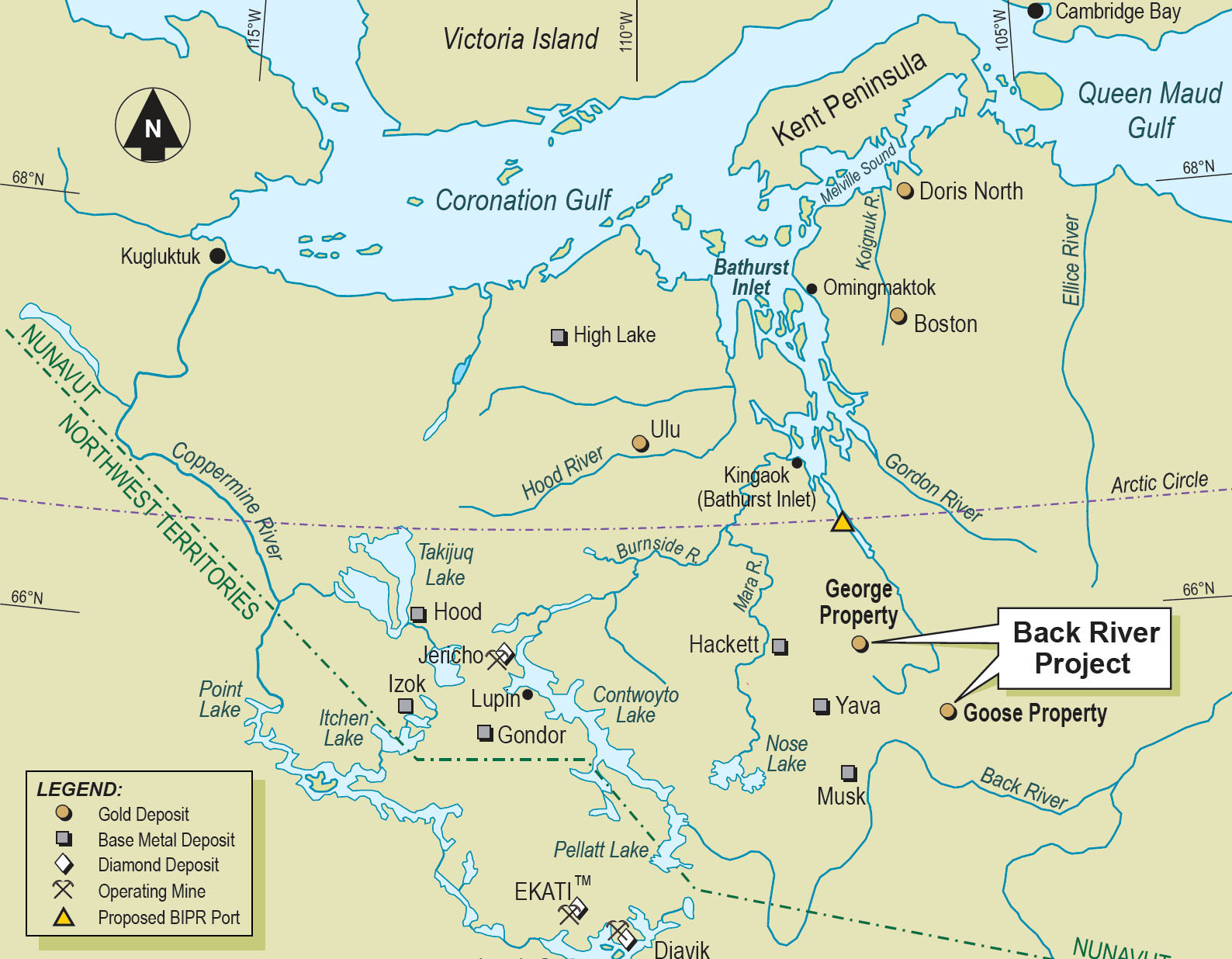

The project, located in Nunavut’s Kitikmeot region, would include a chain of open pit and underground mines at its Goose property along with a 157-kilometer (about 98-mile) road from the mine to a port facility and tank farm in Bathurst Inlet.

It would create an estimated 65 jobs worth $29.6 million for Kitikmeot residents during a four-year construction period and 194 jobs for Kitikmeot residents with an average salary of $114,949 for 10 years, plus contracting opportunities and land lease and royalty revenues for the KIA.

The mine’s potential impact on the region’s dwindling caribou herds became a major issue at a public hearing held last April in Cambridge Bay.

The nearby Bathurst caribou herd was estimated to have a population of 470,000 in 1986, but a 2015 survey showed that number had shrunk to about 16,000.

But following the NIRB’s rejection of Back River, the Kitikmeot Inuit Association, the Government of Nunavut, hamlet councils and hunter and trapper organizations rallied to the mining company’s defence.

The KIA, which owns most of the land the project sits on, even suggested the NIRB may have overlooked KIA’s Aboriginal rights under Section 35 of the constitution.

That’s because the NIRB did not consider a last-minute joint submission that that KIA and GN submitted at the end of a public hearing in Cambridge Bay this past April, proposing new terms and conditions for protecting caribou from the impact of mining operations.

“The NIRB report does not specifically address or consider these terms, and as such, KIA cannot determine if our Section 35 rights have been fully accommodated at this time,” KIA president Stanley Anablak told the federal government in a letter this past August.

So following the NIRB’s rejection of their project, Sabina argued the company has received “broad-based Inuit support,” citing the letters of support from the KIA and hamlet councils in the region.

The World Wildlife Fund, however, raised questions about those proposed mitigation measures.

“Now is not the time to test new, risky mitigation measures when the Bathurst herd has declined to five percent of its historic high and the species as a whole has been newly assessed as ‘threatened’ in Canada,” the World Wildlife Fund’s vice president of Arctic conservation, Paul Crowley, said Feb. 15 in a statement.

And a letter to the NIRB last fall, the Northwest Territories-based Yellowknives Dene First Nation—which previously opposed the project—complained about Sabina’s attempts to lobby the federal government to overturn the NIRB’s decision.

“The Yellowknives Dene First Nation would like to reassure the minister that NIRB is competent and possess[es] the necessary expertise to deliver decisions that are both well-reasoned and fair,” their letter said.

The First Nation accused Sabina of demonstrating contempt for the regulatory process and showing “clear disrespect for both Section 35 consultation and the concerns of northerners.”

“If Sabina truly feels the board has erred in their recommendation, then they should seek remedy through judicial review,” the group wrote.

The NIRB has not indicated the next steps in a new review process.

Sabina said last fall that any new hearings would likely add two years to the mine’s projected timeline for development.

Sarah Rogers and Jim Bell contributed reporting.