Arctic sea ice observers predict a 2019 seasonal low extent that’s typical — for the current low-ice era

The Sea Ice Prediction Network collected 31 predictions for this fall's melt — which averaged a slightly lower extent than last year.

Using a combination of statistical analysis, direct observations, complicated models and some gut feelings, scientists and interested observers have come up with a range of predictions for this year’s end-of-melt-season Arctic sea ice extent.

Some 31 contributors gave predictions to the Sea Ice Prediction Network’s June Sea Ice Outlook, and the median of those predictions was 4.4 million square kilometers, a level nearly perfectly aligned with the rate of ice decline seen since satellite measurements began in 1979.

The Sea Ice Prediction Network is managed by the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States.

The June report is the first of three monthly reports that crunch numbers from individuals or groups trying to predict mean September Arctic sea ice. The range of predictions was wide: The highest predicted mean September sea ice extent was 5.896 million square kilometers, a level not seen since 2006, while the lowest was 3.06 million square kilometers, which would be a new record low.

The prediction for the lowest September sea ice came from a group of young students in Japan. The Sanwa Elementary School group based its prediction on observations of mean ice extent every other year from 2004 to 2018 and from maps showing ice concentration.

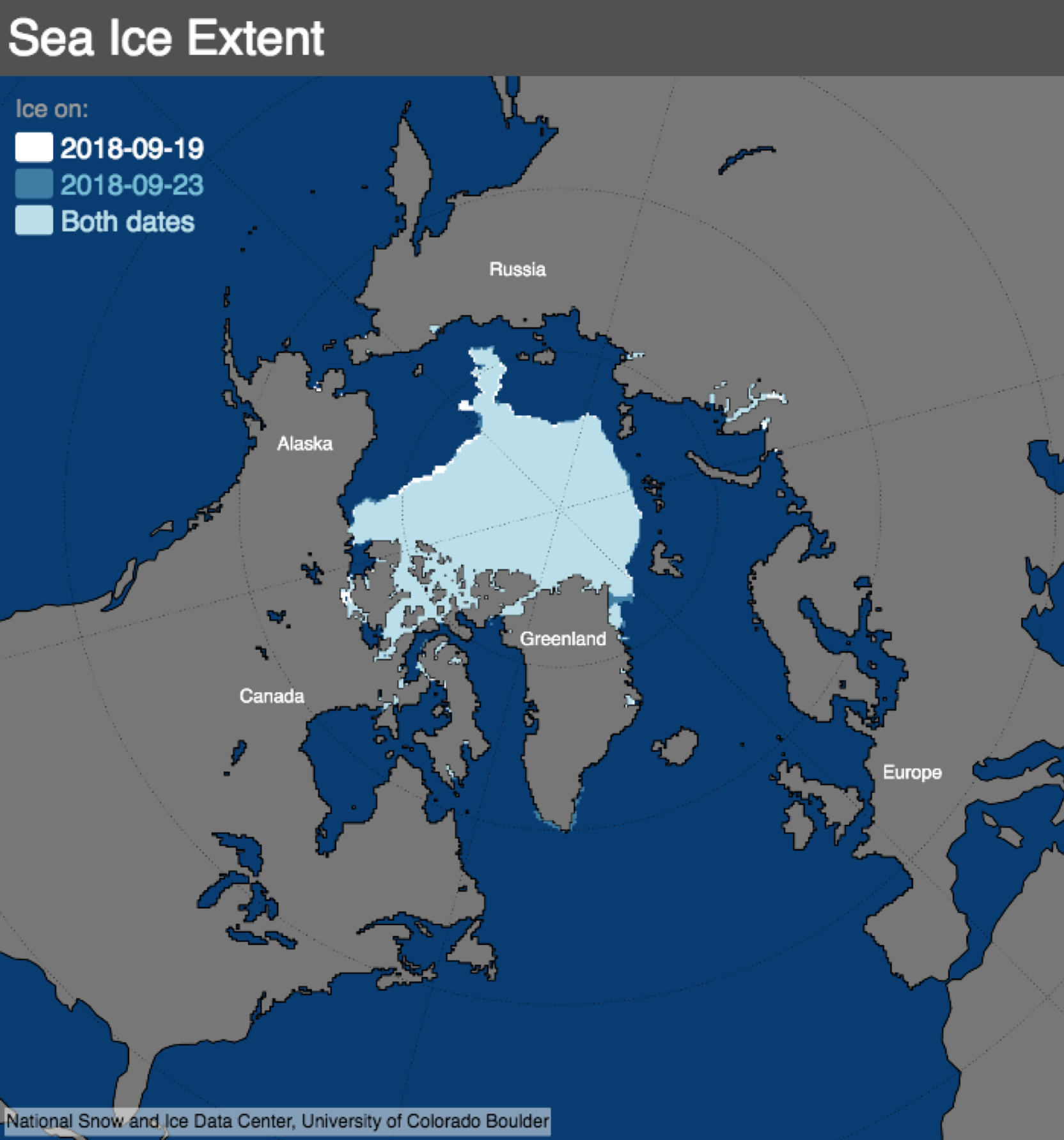

The record-low minimum extent for sea ice was 3.41 million square kilometers, reached on Sept. 15, 2012, and the lowest average September extent, also in 2012, was 3.6 million square kilometers, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Colorado. That year, with its dramatic late meltdown, is considered something of an outlier, driven by some summer weather extremes. Last year’s average September ice extent was 4.71 million square kilometers, the sixth-lowest September average in the satellite record, with the year’s low of 4.59 million square kilometers reached on Sept. 21, according to the NSIDC.

Average September sea ice extent has been declining at a rate of 12.8 percent per decade since 1979, according to the NSIDC.

Of the 31 submissions, one landed right in the middle: the prediction submitted by Brian Brettschneider and John Walsh of the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ International Arctic Research Center. IARC has a model that, when run in early June, indicated that September sea ice “will be nearly identical the extrapolated linear trend of the previous four decades,” the submissions said. The expected September average, according to that analysis: 4.441 million square kilometers.

The methodology used over 3,000 simulations that atmospheric and oceanic conditions in the months leading up to now, with comparison to years with similar patterns, said Brettschneider.

“It came out right on the trend line. It was very unexciting,” he said.

The weakness of the methodology is that it does not anticipate extreme weather conditions like the big heat-up that preceded the 2012 meltdown and that of 2007, which was a record low for its time, Brettschneider said.

But the methodology was good enough to be close to the ultimate result last year. Of the 25 individuals or groups that submitted three monthly predictions in 2018, the IARC prediction turned out to be the fourth best, Brettschneider said.

There is no big reward for accurately predicting the year’s sea-ice loss.

“You get, perhaps, a little bit of bragging rights,” Brettschneider said.

Accurate predictions also give some credibility to whatever method is used, but predicting sea ice requires a full toolbox of methods, he said. “You shouldn’t take one and disregard the others,” he said.