A 9,000-year-old child’s tooth found in Alaska is another link to the vanished Ancient Beringians

DNA from the tooth gives scientists a clearer picture of the Ancient Beringians, a population genetically distinct from modern Native Americans that lived in the North American Arctic.

A 9,000-year old toddler’s tooth found on northwestern Alaska’s Seward Peninsula has revealed important new information about the continent’s early inhabitants.

The tooth has genetic material that links to the Ancient Beringians, a population that lived in Alaska not long after the Bering Land Bridge was inundated by rising seas, according to a study newly published in the journal Science.

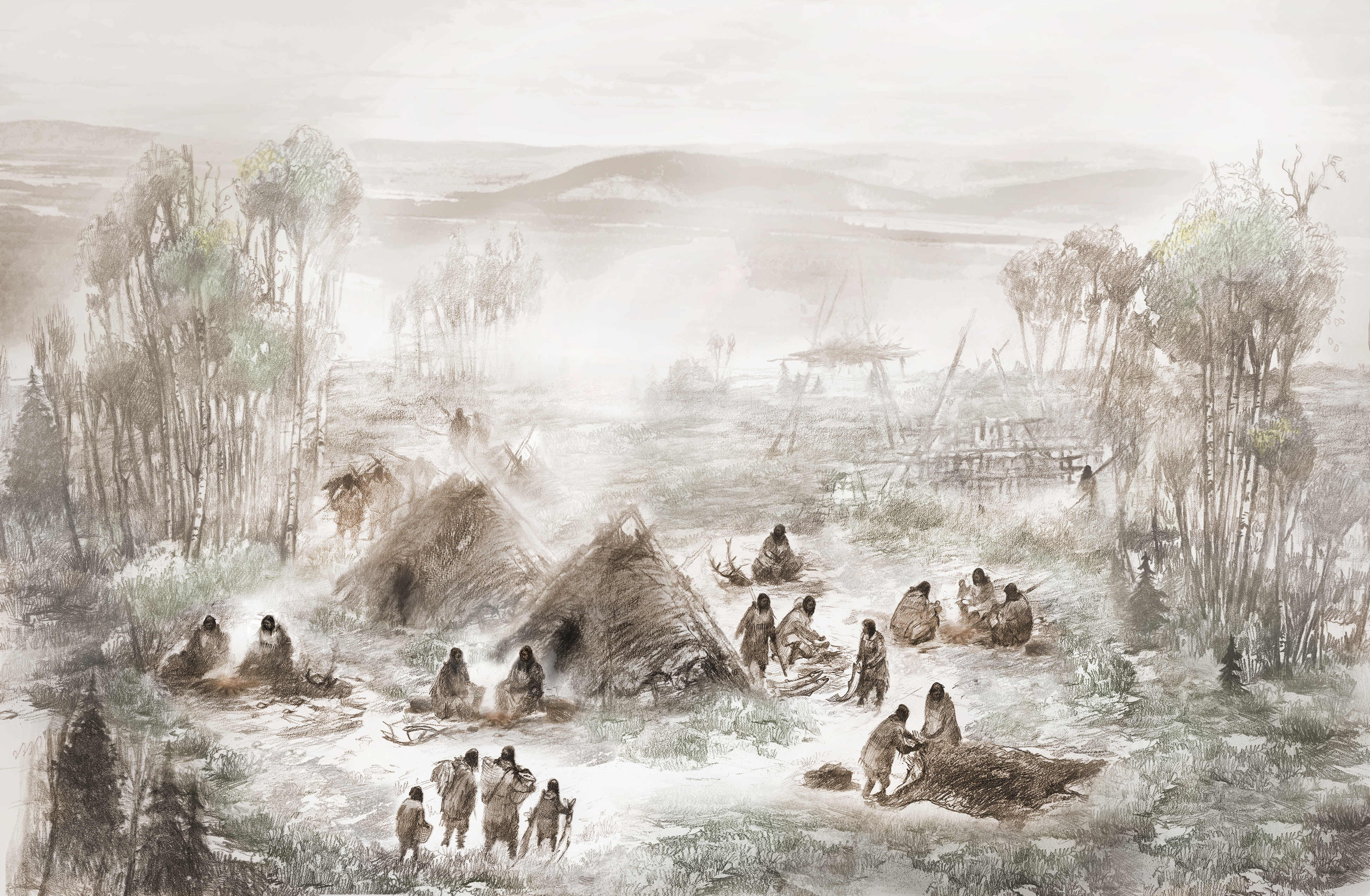

The Ancient Beringians were first identified through remains found in 2013 at the now-famous Upward Sun River site in interior Alaska. Research led by Ben Potter of the University of Alaska Fairbanks identified 11,500-year-old remains there are belonging to a population genetically distinct from modern Native Americans.

The tooth from the Seward Peninsula is the now second discovered piece of Ancient Beringian human remains, officials at UAF said. It is also another piece of information about a population that left distinctive artifacts at several archaeological sites scattered across Alaska and Canada’s Yukon Territory. Those artifacts have long been classified as belonging to the “Denali Complex” tradition.

“This new find confirms our predictions that Ancient Beringians are directly linked with the cultural group known as the Denali Complex, which was widespread in Alaska and the Yukon Territory from 12,500 to about 6,000 years ago,” Potter, who was not involved in the newly published study, said in a statement released by UAF.

The 9,000-year-old toddler tooth is not actually a new discovery. It comes from a place known as the Trail Creek Caves Site, located in what is now Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, that was initially excavated in 1949. But it was held in storage in Denmark for decades and not rediscovered until 2016, when Jeff Rasic, a National Park Service archaeologist, retrieved it as part of his new analysis of the Trail Creek Caves artifacts.

“My inspiration for looking for the tooth was, in short, curiosity,” Rasic, a co-author of the Science paper, said in an email. He was trying to get more precise information about the artifacts from the site, which is special “in that it has excellent preservation of otherwise perishable bone and antler tools.”

Radiocarbon dating revealed that the tooth belonged to a 1 ½-year old child. Study of the tooth included analysis at UAF’s Alaska Stable Isotope Facility, which produced the surprise finding that the child and its mother depended on land-based food, not food from the sea.

“The child’s food sources were entirely terrestrial, a sharp contrast with the other sites that indicate inclusion of anadromous fish and marine resources,” study co-author Matthew Wooller, director of the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility, said in the UAF statement.

The Ancient Beringians, new research shows, were widely dispersed, Rasic said. There are now dozens of known sites that, based on the artifacts found there, have been associated with the Denali Complex or Paleoarctic traditions, he said. Those sites extend across Alaska and into Canada’s Yukon Territory — but have not been found elsewhere in western Canada or in the Lower 48 states, he said.

They are distinct from ancient sites that have been found in southeast Alaska, which hold human remains more than 10,000 years old. DNA analyses in that region “suggest that something different is happening in that area,” Rasic said.

Yereth Rosen is a 2018 Alicia Patterson Foundation fellow.