A new discovery of ancient DNA in Alaska gives fresh clues to ice age human migrations

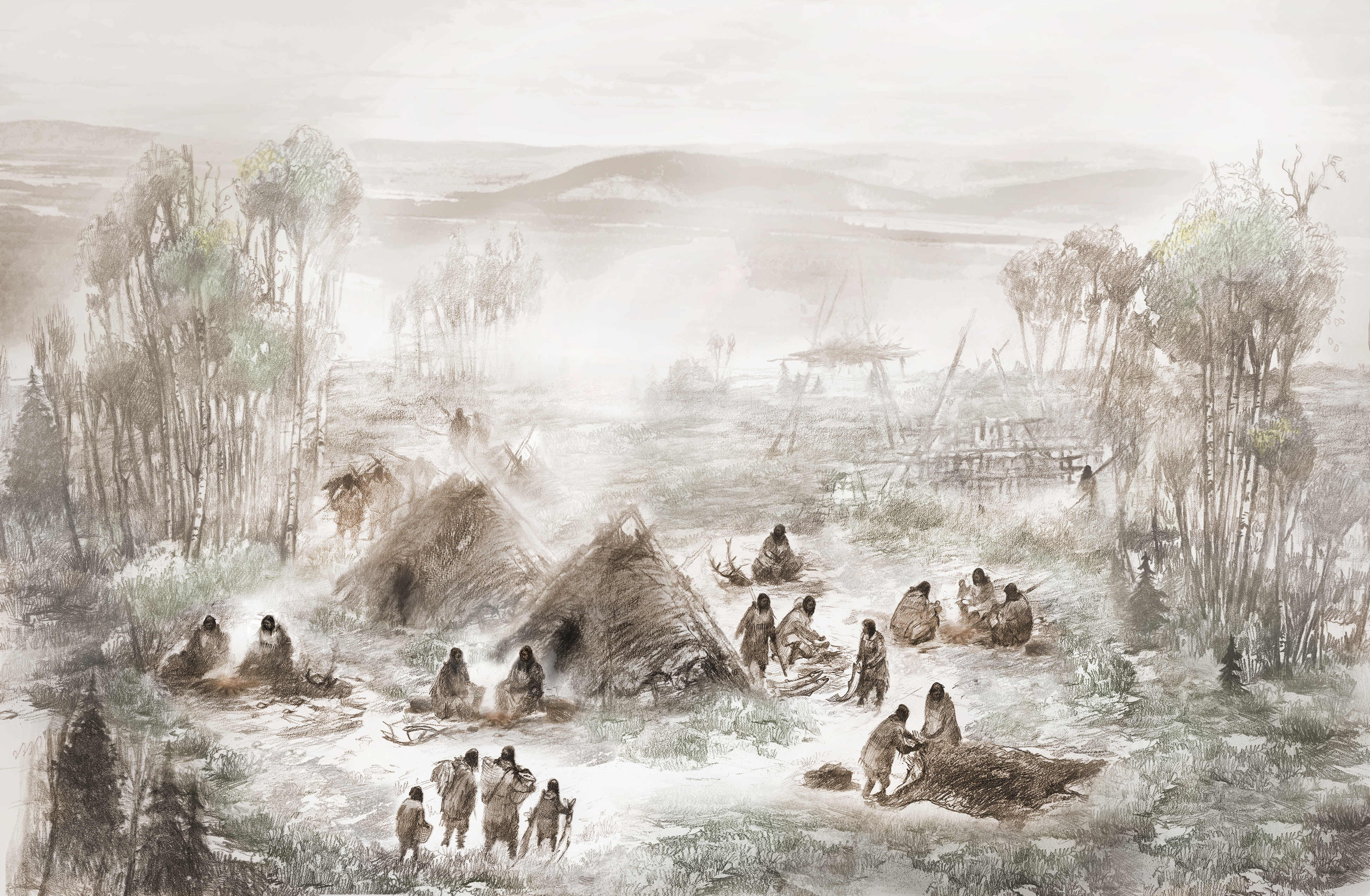

Interior Alaska. (Illustration by Eric S. Carlson in collaboration with Ben A. Potter)

A baby girl who died 11,500 years ago in Alaska has given scientists some stunning new information about how people came to North America, scientists reported this week.

Genetic analysis of the six-week-old girl shows that she is a member of a previously unknown population of ancient humans who either split off from other Asians prior to migration to North America or did so after migration. The newly identified population, called Ancient Beringians, is described in a study published Tuesday in the journal Nature.

Findings are from the landmark Upward Sunrise River archaeological site near Tanana, Alaska.

The girl, named by the region’s Athabascan Xach’itee’aanehn T’eede Gaay, or Sunrise Girl-Child, was discovered buried in an apparently ceremonial manner there. Her remains and those of another baby girl who died preterm and who was named Telkaanenh T’eede Gaay, or Dawn Twilight Girl, are the oldest human remains ever found in Alaska.

Genetic analysis of Sunrise Girl-Child began in 2014 and revealed that although she was related to Native Americans, she was not part of the two general branches of Native Americans, north and south, said Victor Moreno-Mayer of the Centre for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen’s Natural Museum of Denmark and one of the lead authors.

Rather, she “represented a population that diverged from the common ancestor of north and south Native Americans before north and south native americans diverged from each other,” Moreno-Mayer said in a teleconference.

Sunrise Girl-Child’s people likely began to separate from the other Eurasians who crossed over into North America around 20,000 years ago, said Ben Potter, a professor of anthropology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, one of the main investigators of the Upward Sun River site and one of the lead authors.

One scenario is a split in Asia, around the time of the onset of the last glacial maximum, Potter said in the teleconference. “I tend to support that on the archaeological side because that fits with the vast majority of archaeological evidence that we have,” he said.

Another scenario is a split after the groups were in Alaska, he said. Genetics does not give information about migration routes, but there is a “plausible mechanism” for the north and south Native American groups to have migrated on, either along the Pacific coast starting about 16,000 years ago or on an ice-free corridor through Canada that started to open up around 15,000 years ago, he said.

There was some genetic mixing of Ancient Beringians and other Native Americans, but that appears to have ended 6,000 years ago, Potter said.

Exactly what happened to the Ancient Beringians is yet unknown, he said. They could have died out, or they could have been subsumed by the northern North American populations, most likely Athabascans, he said. Further study is planned to try to answer that question.

Even prior to this genetic discovery, the product of work that started in 2014, the Upward Sun River site was famous.

It was discovered about a decade ago when the Alaska Railroad was considering an extension to the Alaska community of Delta Junction. As part of that planning, archeological surveys were conducted along the proposed route, and Potter led those studies. The first discoveries, he said, were of flakes.

The railroad extension never happened, but multiple discoveries at Upward Sun River did, starting with ancient flakes, then excavations that revealed occupation and, in 2013, the two infants.

The site has yielded the first evidence of human use of salmon in the Americas. Studies of salmon use are ongoing, Potter said, and scientists are looking at bones to try to determine maternal diets and see if people were eating stored salmon over the winter, not just eating salmon opportunistically when the fish were running.

“These two infants can provide sort of unparalleled opportunity to study that question,” he said.

The Ancient Beringians at Upward Sun River also used a “distinctly Asian” microblade technology associated with sites in places like China, Japan, Mongolia and Siberia, Potter said.

“Imagine really small razor blades maybe an inch long and half an inch wide that would be produced in quantities that could be then inset into composite opera points made out of bone or antler,” he said. “At least that technology seems to be clearly linked with this ancient Beringian population.”

But the microblade technology is not found much farther south or east, he said.

While identification of the Ancient Beringian population is new, knowledge about the human culture is not, Potter said. The Upward Sun River people are associated with a culture known as Denali or Paleoarctic, the most widespread cultural group present in the Ice Age or early Holocene in northwestern North America, he said. Sites dating from about 12,500 years ago to about 6,000 years ago have been found in Alaska and neighboring parts of Canada, he said.

The Ancient Beringians have more lessons to teach modern people, he said.

“Now we know that these people were here. They established themselves over many thousands of years. There were a very successful population in the far north,” he said. That raises questions about climate change and adaptation, he said.

“This was the last major period of sort of profound and significant climate shifts and extinctions that we haven’t seen until the present day. And we’re looking at major climate change now, and extinctions,” he said.