What does it mean to be ‘true north strong and free?’ Canada’s elusive northern identity

So far, ideas of "Northern" identity have been shaped by — and for — people in Canada's South.

From the national anthem to the Toronto Raptors (#WeTheNorth), Canada is frequently framed as a northern country, its citizens a northern people. But what exactly does it mean to live in the “true north strong and free?”

If you were to ask Alfred Tennyson, one of the first to describe the country as “that true North” in his poem To the Queen, Canada was the “true North,” as in it was loyal to the British Crown. As few today are likely to share this interpretation, it hints both at how dramatic the shift in Canada’s northern identity has been — and its political implications.

As Canadians head to the polls, it’s worth reflecting on how politicians have presented Canada as “North,” both past and present.

Canada First

Long before “America First” became a partisan rallying cry south of the border, there was a short lived (1868-1876) but influential political movement called “Canada First” that located the country’s fledgling identity in its northernness.

For the founders of this nationalist movement, the newly confederated Dominion of Canada was already distinguished by its northern character. Drawing on a “survival of the fittest” mentality inspired by Darwinian evolution, the long and unforgiving winters were credited with forging an especially resilient, hearty and masculine people.

Canadians were, as William A. Foster, one of the founding figures wrote: “A Northern people, — as the true out-crop of human nature, more manly, more real, than the weak marrow-bones superstition of an effeminate South.”

Not only did this encourage young men to strike out in the Northwest and settle new land as a means of “proving their manliness,” but it also rooted Canadian identity in a hyper-masculinized northern environment. This simultaneously naturalized a link between the settler and the land and worked to delegitimize Indigenous connections to the land.

A new Canada of the North

If the Canada First movement was short lived, the idea that Canada was already North was not. With a few exceptions (like the Klondike gold rush), the eyes of Canada’s political elite rarely turned to the far North and it was long governed from Ottawa as a pseudo-colony, with the prime minister appointing both the executive and legislative branches of territorial governments.

Ideas of Canada’s northern identity re-emerged with John Diefenbaker’s surprise electoral victory in 1957. An important pillar of his platform, a “Northern Vision” again located Canada’s future in the North.

This vision, to Diefenbaker, represented nothing less than Canada expanding to fill its natural borders: “We are fulfilling the vision and the dream of Canada’s first prime minister — Sir John A. Macdonald. But Macdonald saw Canada from East to West. I see a new Canada. A Canada of the North.”

This “new Canada of the North” was not the thin strip of settlements nestled along the American border, but instead the northern territories. Framed as vast, empty and primitive, their resources were thought to be the catalyst of an economic boom which would bring about untold prosperity.

New roads would connect the North, and modern cities replete with suburbs and skyscrapers would rise from the permafrost. As a 1964 Maclean’s article critical of the lack of progress put it, this would contribute to “the rescue of Canada’s primitive people, Eskimo and Indian, from the Stone Age and their introduction to the twentieth century.”

Ghosts of Arctics past

When former prime minister Stephen Harper formed the government in 2006, he resurrected many elements of Diefenbaker’s nationalist “Northern Vision” within the context of an increasingly international Arctic.

This time, however, the North’s resource wealth had to be protected from other nations who might challenge Canada’s sovereignty. Set against the larger rebranding of Canada as a warrior nation, what it meant to be a northern nation shifted to focus more on military strength and the capacity to defend Canada’s Arctic claims.

Harper also summoned the ghosts of the ill-fated 1848 Franklin Expedition to shore up contemporary political goals. In a bit of revisionist history, British polar exploration was positioned as a central component of Canadian heritage — and one that was argued to have “laid the foundations of Canada’s Arctic sovereignty.”

Negotiating North during Canada’s 44th election

In the post-Harper era, questions of Canada’s northern identity have faded from the mainstage of federal politics with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pivoting from his predecessor’s emphasis on the Arctic.

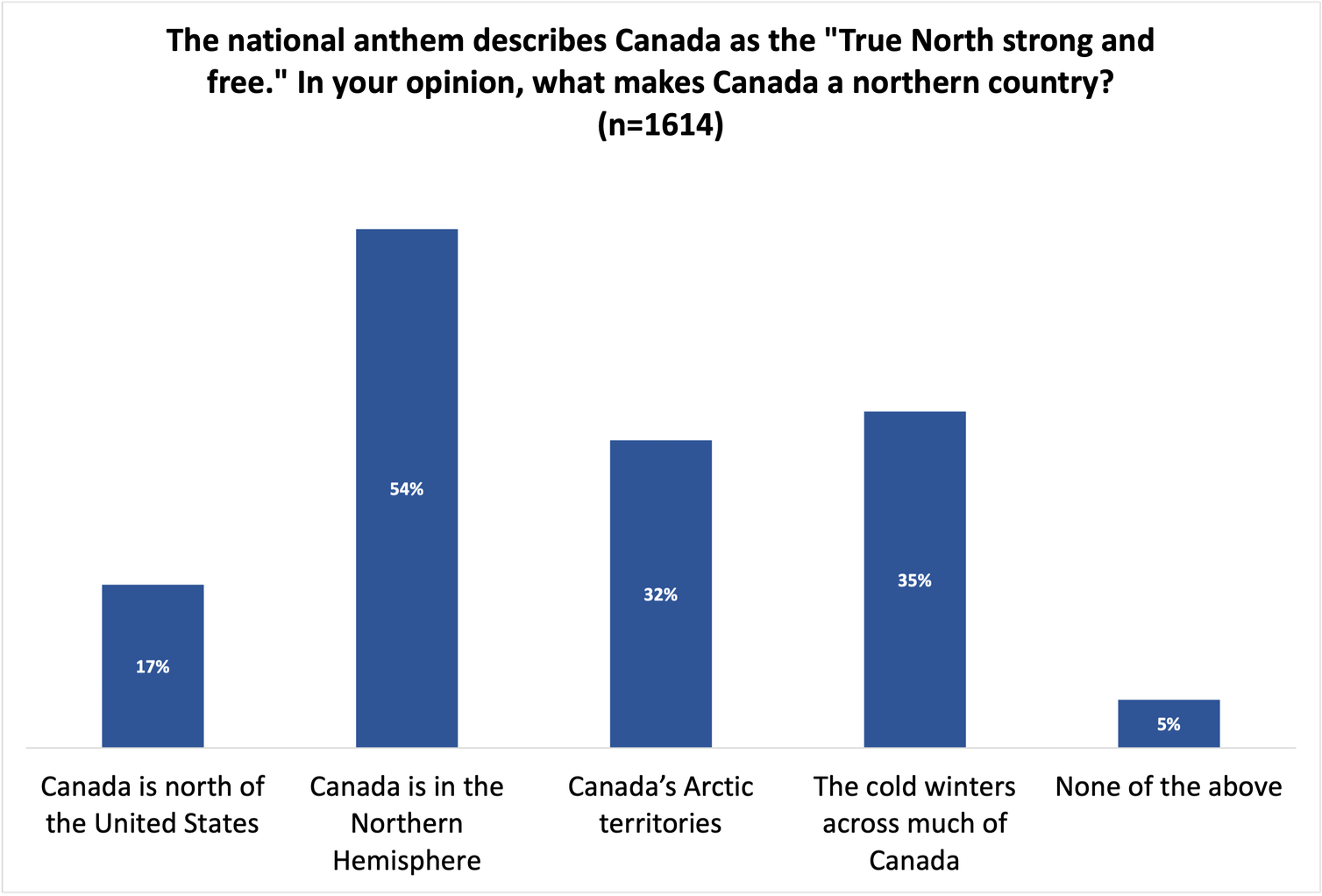

Canadians, for their part, are of many minds about what anchors their northern identity. A recent national survey by the Angus Reid Institute reveals that notions of “North” vary dramatically.

If this very brief history of Canada’s northern identity reveals anything, it’s that ideas of North have predominantly been created by, and importantly for, those living in the South.

Whoever becomes prime minister after the upcoming election must reckon with this and exorcise dated depictions of the North as a site of imperial expansion that is valued only for its potential material wealth, or as a highly militarized space.

Instead, let’s listen to those who call the North home. As president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami Natan Obed compellingly argues, it’s time to let the North define itself discursively and politically — only then can it be the “true North.”

Gregor Sharp is a PhD Candidate in political science at University of British Columbia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.