A warming Arctic means mussels are moving northward along Greenland’s coast

Scientists have found that warming temperatures help these non-native species survive the winter.

A warming Arctic means a changing Arctic, and scientists are racing to figure out exactly what that will look like.

Researchers have strapped cameras to polar bears or warmed small lakes with pool heaters to raise Arctic graylings in a manmade “fish spa” — all to try to understand how Arctic ecosystems will react to climate change.

But in Greenland, scientists didn’t have to go to these extreme lengths to see how some species may adapt to the warming Arctic. That’s because it’s happening in real time.

Using the west coast of Greenland as a natural science lab, a new study from researchers at Aarhus University in Denmark and the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources details how blue mussels — the mollusk usually found on restaurant menus — will increase in the Arctic as the region warms.

“When you visit Greenland and talk to the local hunters and fishermen, you quickly understand that climate changes already affect these people in so many ways, every day,” Jakob Thyrring, a post-doctoral researcher at Aarhus’ Arctic Research Center and lead author of the study, wrote in an email.

Blue mussels are non-native to the region but are considered a foundation species, which means that they play a large role in the ecosystem. While they may compete with native species, they also support different fauna as they form dense layers in open spaces, known as “mussel beds.” These thick layers can protect different species while also providing a hard surface for others to grow. For now, they are only found in abundance in southern Greenland.

The researchers focused on western Greenland’s intertidal zone, which is exposed during low tide and under water during high tides. They collected mussels from 73 sites during four consecutive summers, with locations ranging from the far subarctic south to the High Arctic north. They also collected air temperature measurements using loggers, and using data from the Danish Meteorological Institute calculated the average number of days with an average temperature below negative 13 degrees Celsius, where 50 percent of mussels have been shown to die after two hours of exposure.

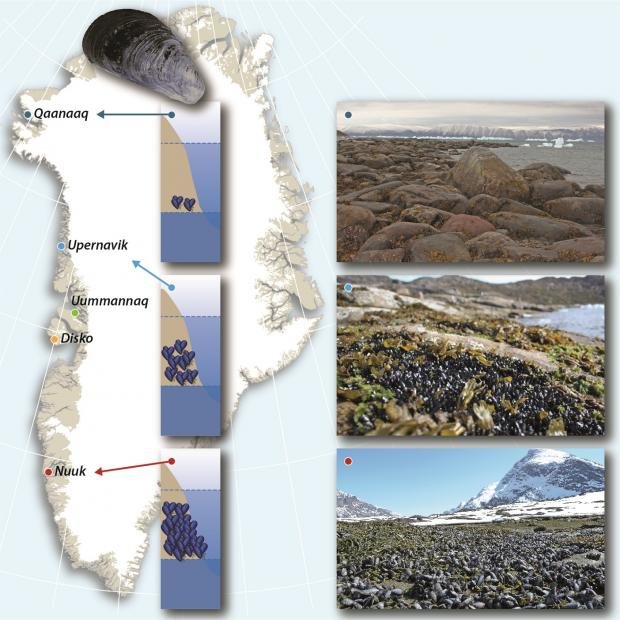

Using these measurements, the researchers found that the number of days below negative 13 degrees Celsius decreased by 57 percent in Greenland from 1990 to 2011. Looking at the more than 5,000 mussels collected, they found that the most were from the capital Nuuk in the south, and that numbers declined the further north they went.

The researchers attributed this decline to young mussels’ low tolerance to cold temperatures — they die off in northern sites before they can reach adulthood. Northern mussels could only survive in gaps between rocks, while southern mussels could live out in the open.

But simply the presence of mussels so far north surprised researchers.

“Blue mussels are also found on Svalbard, but only in the subtidal where they are protected from low air temperatures,” wrote Thyrring. “Thus their presence in High Arctic Greenland truly show how good they are in adapting to extreme environments.”

In the email, Thyrring said there might be other important factors to help explain why there are fewer mussels up north, from different ocean currents to drifting sea ice. His team is considering the impacts of these interactions using field and lab experiments.

Northern Greenland is expected to see rising air temperatures in upcoming decades, so the scientists then used their observations from southwestern Greenland to project how the mussel population will thrive with these climatic changes. Because cold days were one of the only factors keeping mussel populations at bay, the scientists project that, as these cold days decrease, the mussels will expand northward.

“If blue mussels expand further north (and become more abundant) they may change the ecological dynamics and carbon flow,” wrote Thyrring. “However, we still do not fully understand the consequences of their expansion.”

That includes whether there are any benefits to a northward expansion of blue mussels, such as economic opportunities or habitat for other species.

“So perhaps there could be a positive response in richness and abundance of other species following a blue mussel expansion,” Thyrring said, “but we do not know.”