U.N. climate change report sounds ‘code red for humanity’

"The alarm bells are deafening."

The United Nations panel on climate change told the world on Monday that global warming was dangerously close to being out of control — and that humans were “unequivocally” to blame.

Already, greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere are high enough to guarantee climate disruption for decades if not centuries, the report from the scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned.

In other words, the deadly heat waves, gargantuan hurricanes and other weather extremes that are already happening will only become more severe.

Monday alone saw 500,000 acres of forest burning in California, while in Venice tourists waded through ankle-deep water in St. Mark’s Square.

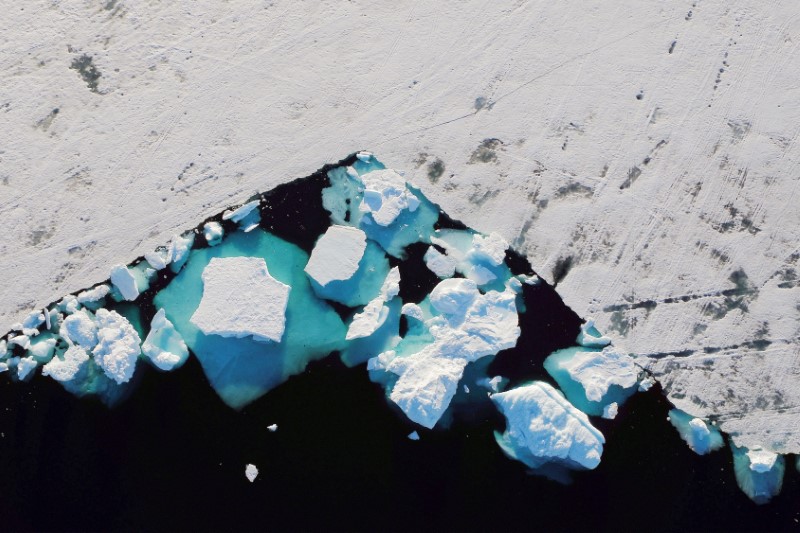

For the Arctic — which is already warming three times faster than the rest of the planet — one key takeaway from the report was the prediction that the Arctic Ocean will be free of sea ice in the summer at least once by 2050.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres described the report as a “code red for humanity.”

“The alarm bells are deafening,” he said in a statement. “This report must sound a death knell for coal and fossil fuels, before they destroy our planet.”

In an interview with Reuters, activist Greta Thunberg called on the public and media to put “massive” pressure on governments to act.

In three months, the U.N. COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, will try to wring much more ambitious climate action out of the nations of the world, and the money to go with it.

Drawing on more than 14,000 scientific studies, the IPCC report gives the most comprehensive and detailed picture yet of how climate change is altering the natural world — and what could still be ahead.

Unless immediate, rapid and large-scale action is taken to reduce emissions, the report says, the average global temperature is likely to reach or cross the 1.5-degree Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) warming threshold within 20 years.

The pledges to cut emissions made so far are nowhere near enough to start reducing level of greenhouse gases — mostly carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels — accumulated in the atmosphere.

‘Wake-up call’

Governments and campaigners reacted to the findings with alarm.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said he hoped the report would be “a wake-up call for the world to take action now, before we meet in Glasgow.”

U.S. President Joe Biden tweeted Monday: “We can’t wait to tackle the climate crisis. The signs are unmistakable. The science is undeniable. And the cost of inaction keeps mounting.”

The report says emissions “unequivocally caused by human activities” have already pushed the average global temperature up 1.1 degrees C from its pre-industrial average — and would have raised it 0.5 degrees C further without the tempering effect of pollution in the atmosphere.

That means that, even as societies move away from fossil fuels, temperatures will be pushed up again by the loss of the airborne pollutants that come with them and currently reflect away some of the sun’s heat.

A rise of 1.5 degrees C is generally seen as the most that humanity could cope with without suffering widespread economic and social upheaval.

The 1.1 degrees C warming already recorded has been enough to unleash disastrous weather. This year, heat waves killed hundreds in the Pacific Northwest and smashed records around the world. Wildfires fuelled by heat and drought are sweeping away entire towns in the U.S. West, releasing record carbon dioxide emissions from Siberian forests, and driving Greeks to flee their homes by ferry.

Further warming could mean that in some places, people could die just from going outside.

“The more we push the climate system … the greater the odds we cross thresholds that we can only poorly project,” said IPCC co-author Bob Kopp, a climate scientist at Rutgers University.

Irreversible

Some changes are already “locked in.”

Greenland’s sheet of land-ice is “virtually certain” to continue melting, and raising the sea level, which will continue to rise for centuries to come as the oceans warm and expand.

“We are now committed to some aspects of climate change, some of which are irreversible for hundreds to thousands of years,” said IPCC co-author Tamsin Edwards, a climate scientist at King’s College London. “But the more we limit warming, the more we can avoid or slow down those changes.”

But even to slow climate change, the report says, the world is running out of time.

If emissions are slashed in the next decade, average temperatures could still be up 1.5 degrees C by 2040 and possibly 1.6 degrees C by 2060 before stabilizing.

And if, instead the world continues on its the current trajectory, the rise could be 2 degrees C by 2060 and 2.7 degrees C by the century’s end.

The Earth has not been that warm since the Pliocene Epoch roughly 3 million years ago — when humanity’s first ancestors were appearing, and the oceans were 25 meters (82 feet) higher than they are today.

It could get even worse, if warming triggers feedback loops that release even more climate-warming carbon emissions — such as the melting of Arctic permafrost or the dieback of global forests.

Under these high-emissions scenarios, Earth could broil at temperatures 4.4 degrees C above the preindustrial average by the last two decades of this century.

Reporting by Nina Chestney in London and Andrea Januta in Guerneville, California; Additional reporting by Jake Spring in Brasilia, Valerie Volcovici in Washington, and Emma Farge in Geneva.