Typhoon Merbok pounded Alaska’s vulnerable coastal communities at a critical time

The storm was fueled by unusually warm Pacific Ocean.

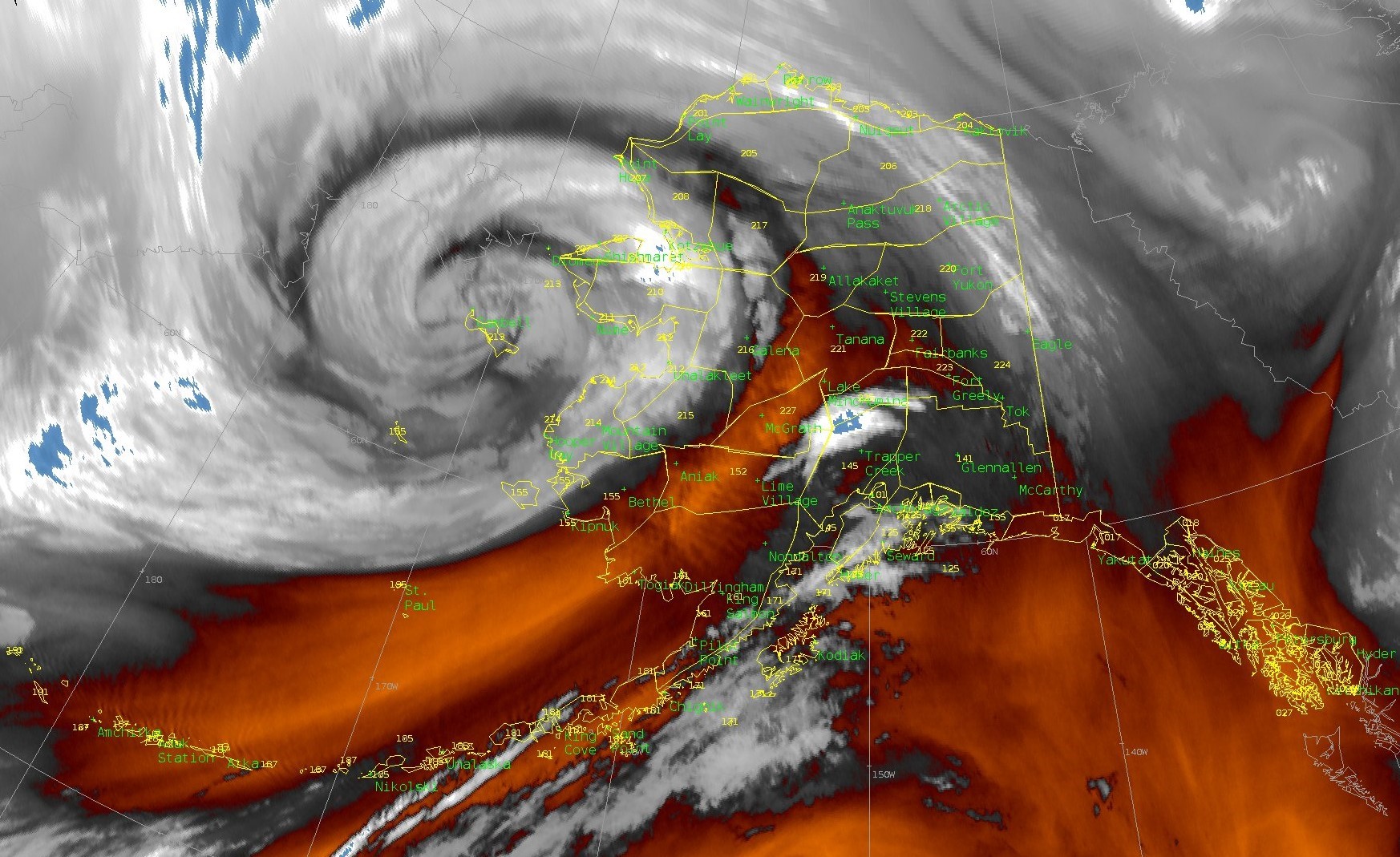

The powerful remnants of Typhoon Merbok pounded Alaska’s western coast on Sept. 17, 2022, pushing homes off their foundations and tearing apart protective berms as water flooded communities.

Storms aren’t unusual here, but Merbok built up over unusually warm water. Its waves reached 50 feet over the Bering Sea, and its storm surge sent water levels into communities at near record highs along with near hurricane-force winds.

Merbok also hit during the fall subsistence harvest season, when the region’s Indigenous communities are stocking up food for the winter. Rick Thoman, a climate scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, explained why the storm was unusual and the impact it’s having on coastal Alaskans.

What stands out the most about this storm?

It isn’t unusual for typhoons to affect some portion of Alaska, typically in the fall, but Merbok was different.

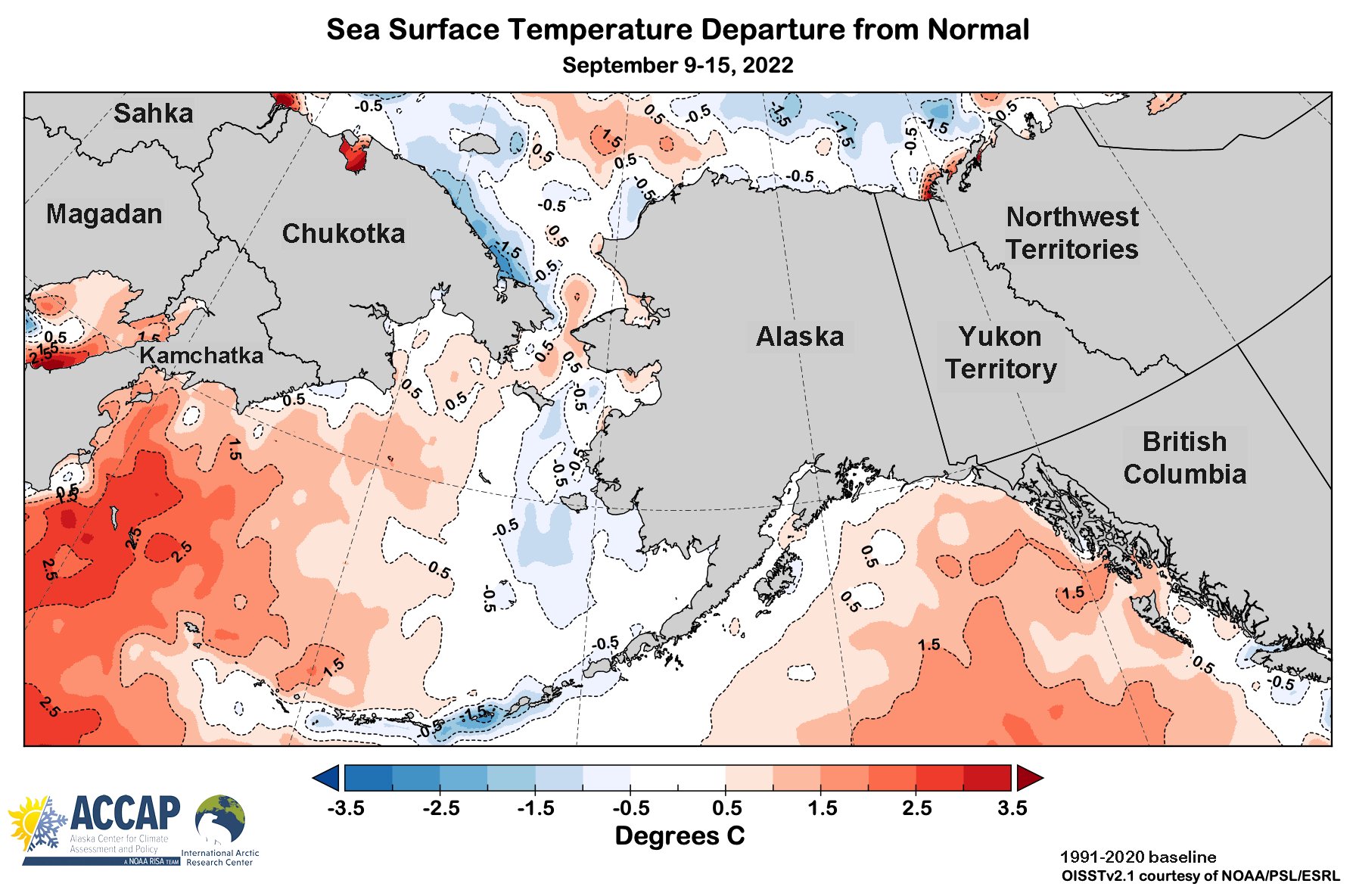

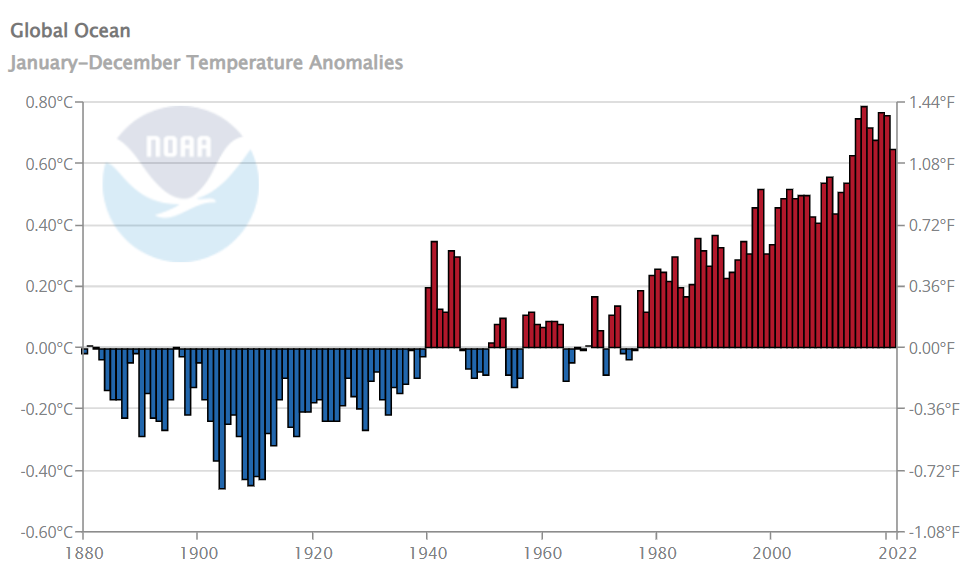

It formed in a part of the Pacific, far east of Japan, where historically few typhoons form. The water there is typically too cold to support a typhoon, but right now, we have extremely warm water in the north-central Pacific. Merbok traveled right over waters that are the warmest on record going back about 100 years.

The Western Bering Sea, closer to Russia, has been running above normal sea surface temperature since last winter. The Eastern Bering Sea — the Alaska part — has been normal to slightly cooler than normal since spring. That temperature difference in the Bering Sea helped to feed the storm and was probably part of the reason the storm intensified to the level it did.

When Merbok moved in to the Bering Sea, it wound up being by far the strongest storm this early in the autumn. We’ve had stronger storms, but they typically occur in October and November.

Did climate change have a bearing on the storm?

There’s a strong likelihood that Merbok was able to form where it did because of the warming ocean.

With warm ocean water, there’s more evaporation going in the atmosphere. Because all the atmospheric ingredients came together, Merbok was able to bring that very warm moist air along with it. Had the ocean been a temperature more typical of 1960, there wouldn’t have been as much moisture in the storm.

How extreme was the flooding compared to past storms?

The most outstanding feature as far as impact is the tremendous area that was damaged. All coastal regions north of Bristol Bay to just beyond the Bering Strait — hundreds of miles of coastline — had some impact.

At Nome — one of the very few places in western Alaska where we have long-term ocean level information — the ocean was 10.5 feet (3.2 meters) above the low-tide line on Sept. 17, 2022. That’s the highest there in nearly half a century, since the historic storm of November 1974.

In Golovin and Newtok, multiple houses floated off their foundations and are no longer habitable.

Shaktoolik lost its protective berm, which is very bad news. Prior to building the berm, the community’s freshwater supply was easily inundated with saltwater. The community is now at greater risk of flooding, and even a moderate storm could inundate their fresh water supply. They can rebuild it, but how fast is a matter of time and money and resources.

Another important impact is to hunting and fishing camps along the coasts. Because of the region’s subsistence economy, those camps are crucial, and they are expensive to rebuild.

There are no roads into these coastal communities, and getting lumber for rebuilding homes and these camps is difficult. And we’re moving into typically the stormiest time of year, which makes recovery harder and planes often can’t land.

Lots of places also lost power and cell phone communication. The power in these remote areas is generated in the community — if that goes out there is no alternative. People lose power to their freezers, which they’re stocking up for the winter. Towns might have one grocery store, and if that can’t open or loses power, there is no other option.

Winter is coming, and the time when it’s feasible to make repairs is running short. This is also the middle of hunting season, which in western Alaska is not recreation — it’s how you feed your family. These are almost all predominantly or almost exclusively Indigenous communities. Repairs are going to take time away for subsistence hunters, so all of these things are coming together at once.

Does the lack of sea ice as a buffer make a difference for erosion?

Historically, with storms later in the season, even a small bit of sea ice can offer protection to dampen the waves. But there’s no ice in the Bering Sea at all this time of year. The full wave action pounds right to the beach.

As sea ice declines with warming global temperatures, communities will see more damage from storms later in the year, too.

Are there lessons from this storm for Alaska?

As bad as this storm was, and it was very bad, others will be coming. This is a stormy part of the world, and state and federal governments need to do a better job of communicating risks and helping communities and tribes ahead of time.

That might mean evacuating vulnerable people. Because if you wait until it’s certain that there’s a problem, it’s too late. Almost all of these communities are isolated.

I would say this is a classic case of large-scale weather models showing a general idea of the risk far in advance, but it takes longer to respond for isolated communities like those in rural Alaska. By Sept. 12, Merbok’s storm track was clear, but if communities aren’t briefed until a day or two days before the storm, there isn’t enough time for them to fully prepare.

Rick Thoman is Alaska climate specialist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.