Two U.S. bills could advance American presence in the Arctic

The Arctic Policy Act and the SEAL Act would help develop U.S. Arctic strategies, especially around shipping.

A pair of bills due to be introduced in Congress later this year could help strengthen the United States’ role in the Arctic, say backers.

The two bills — the Arctic Policy Act (APA) and the Shipping and Environmental Arctic Leadership Act (SEAL Act) — were both introduced late last year, but saw little movement before the session ended.

Alaska Sen. Murkowski, a Republican, plans to reintroduce them this spring.

Addressing the Alaska State Legislature on February 19, Murkowski framed both pieces of legislation as ways to shore up resources for Alaska and to compete on an increasingly international stage.

The two bills, she said, would work to “reinvigorate America’s approach to the Arctic, bringing Indigenous voices to Arctic policy, and also to counterbalance Russia’s increasing dominance over Arctic shipping.”

“We can’t forget about the people of the Arctic. We can’t forget about the people who live there,” she said. The legislation would, “most importantly and notably,” provide funding for personnel to create a working Arctic policy for the country.

The first step toward building a stronger American presence in the Arctic, Murkowski said, is fully funding polar security cutters, also known as icebreakers. After that, building infrastructure in the Arctic would be key.

“Most critical for that is the development of a deepwater port in the Bering Sea,” she said. “It can serve many, many uses. It can support the Navy, the Coast Guard, NOAA’s research mission. It will support search and rescue activities that may be necessitated by increasing commercial vessel traffic in the Arctic.”

Taken together, the two bills suggest the Arctic is growing in significance in Washington. While that focus tends to linger on security concerns, the Arctic is also seeing a rise in construction, tourism, natural resource extraction, shipping and community development, Murkowski pointed out when she introduced the legislation late last year: “The race to protect America’s strategic interests in the Arctic demands attention on more than just defense.”

The Arctic Policy Act

The APA bill would put into law the Arctic Executive Steering Committee, which was originally created by an Obama-era executive order. Although the order has not been rescinded, the Trump administration has left the committee dormant for the past two years.

John Farrell, executive director of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission who served on the committee, said, “We were working on shipping, energy issues, science issues, diplomacy, Coast Guard — you name it. And it really was, in my opinion, a quite effective way to bring coordination on Arctic issues to the forefront.”

The bill would not only codify the committee, it would also transfer its chairmanship to the Department of Homeland Security, rather than the White House.

“That way, it’s not based on each administration,” Farrell said. “There would be long-term responsibility for this regardless of who is president. And it would be in law, so it couldn’t easily be rescinded or eliminated, unless the law was changed.”

Murkowski called the committee “the central coordinating body for Arctic issues” in the U.S. government. It would create a strategic plan and coordinate it across government agencies, she said.

In addition, the APA bill would also establish an Arctic Advisory Committee with members representing Alaska’s eight Arctic regions (Arctic Slope, North West Arctic, Norton Sound, Interior, Yukon-Kuskokwim, Bristol Bay, the Aleutian Islands, and the Pribilof Islands). It would also establish regional tribal advisory groups, starting with the Bering Sea Regional Tribal Advisory Group, which was created by an Obama executive order but rescinded by the Trump administration. And it would add two Indigenous commissioners to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission.

Indigenous communities in Alaska have an advanced knowledge of the Arctic and deserve a seat at the table, Murkowski said in December. “In the Arctic, we’ve got an opportunity to show the world here how to integrate Indigenous knowledge and voices into policy and science.”

The Shipping and Environmental Arctic Leadership Act (SEAL Act)

The SEAL Act, sometimes called “Uber for icebreakers,” would move to begin developing a safe, secure and reliable Arctic seaway, Murkowski said, and it would “further ensure the Arctic becomes a place of international cooperation, rather than competition or conflict.”

The idea draws from the example of the St. Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation, which stretches from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. A vessel might cross the U.S.-Canadian border a dozen times, but if it encounters trouble at any point, there’s a single international organization upon which to call.

Similarly, this act would establish an Arctic seaway development corporation that would collect a voluntary fee — as much as $500,000 — from each vessel traversing the U.S. Arctic. Those who pay the fee would receive maritime support, such as icebreaker assistance if they hit a rough spot. Those icebreakers would come from the U.S. Coast Guard and private U.S. fleets, as well as from other nations.

“When you can figure out a quicker way to get from Asia to Europe, when you can shave off days, when you can use less fuel — you are saving money,” Murkowski said in December when she introduced the bill. “From a trade perspective, this is hugely significant.”

An increase in Arctic shipping will lead to increased demands for support services — such as icebreaker support, harbors of refuge, ice forecasting, oil spill response, and support from a response tug if a vessel loses power or steerage — but those services cost money.

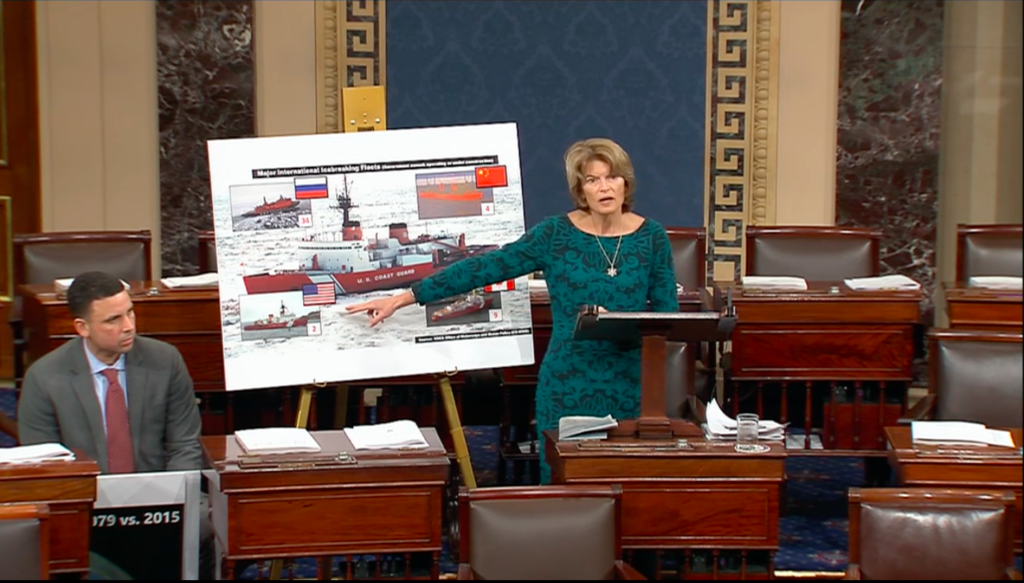

Take icebreakers, for instance. The U.S. icebreaker fleet contains only one medium polar-class vessel working in the Arctic, with one heavy icebreaker working in Antarctica and another recently funded for construction. The United States’ ability to provide icebreaking services or conduct search-and-rescue missions is already severely limited.

The U.S. Arctic Seaway Infrastructure Development Corporation that would be established by the SEAL Act would use the voluntary funds it collects to pay, for instance, for a rented icebreaker from Canada or Finland — hence the “Uber for icebreakers” moniker.

The funds would also support the construction of a system of deepwater ports in the U.S. Arctic in order to provide services for ships traveling through the region.

“Port infrastructure will also benefit rural Arctic communities and bring down costs for delivering fuel, groceries, and other necessities, which in my state at this time are just extraordinarily high,” Murkowski said.

Many of the ideas in the SEAL Act have been championed in the past by Mead Treadwell, former lieutenant governor of Alaska, former chair of the Arctic Circle’s Mission Council on Shipping and Ports and co-chair of the Polar Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

“We want to make sure the shipping is done safely,” he said. “This is a mechanism to help get there.”

“We’ve written the rules,” he continued, referring to the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code. But “we haven’t figured out a way to get the resources there.”

If the Arctic were to see 5 to 10 percent of the traffic currently moving through the Suez Canal, he said, that would mean an additional 900 to 1,800 vessels in Arctic waters every year. And if big ships cost, say, $100,000 to operate each day they are at sea, cutting their journey down by two weeks would mean a savings of $1.4 million — making the $500,000 fee economically feasible, he said — “provided the service is reliable.”

“Because nobody owns the Arctic,” he said, “it’s really incumbent on us to set out an organizational effort that can bring enough money in to pay for the infrastructure to make the ocean safe.”

While Treadwell wants this legislation to “change the impression of the United States in the Arctic,” he argued that the U.S. isn’t going to claim it can control the region, “like the Russians have in the Northern Sea Route.”

“The idea here is to make sure that the Arctic is not the province of any one nation,” he said.

Yet some Arctic observers have questioned whether the United States would be violating international laws by collecting fees to help vessels traverse the ocean.

Ambassador David Balton, a senior fellow with the Wilson Center’s Polar Institute, cautioned that a bill calling upon foreign vessels to pay certain fees to the United States for the privilege of sailing in U.S. waters “will be an issue for sure.”

“Generally speaking, vessels do not have to pay money simply to transit ocean spaces,” he told ArcticToday. “And the U.S. is among the biggest champions of freedom of navigation like that.”

However, he said, there are exceptions to those rules, particularly for boats coming into ports.

“Those will be among the issues that will have to be examined carefully if the bill is going to pass,” he said.

Although making the fee voluntary may avoid violating those international laws, he said, “you might wonder who would actually pay it.”

Ensuring icebreaker support would be useful, he said. “But the United States is one of the richest countries in the world, if not the richest. It should be building its icebreakers anyway for its own purposes.”

“Maybe this dynamic can be made to work,” he said. “We don’t know yet, do we?”

However, he said, preparing for expected increases in shipping in the Bering Strait region and the Arctic generally is a good idea, and some aspects of the bill would better position the United States to deal with those changes.

“I’m glad at least some people in Congress are focused on this, because there certainly will be an increase in shipping in the years to come,” Balton added. “And we are not, as a country, well-prepared to deal with that.”