Russian scientists find 7,000 Siberian hills possibly filled with explosive gas

Russian scientists recently discovered 7,000 earthen knobs erupting from the Siberian Arctic, each the size of a small hill. It was as though the permafrost had broken out into giant grass-covered mounds. What’s more, an unknown number of these bubbles could contain methane and explode, forming craters, the Siberian Times reported.

Using a combination of satellite images and field study, the researchers tallied the bumps. They found far more than previously counted. “At first such a bump is a bubble, or ‘bulgunyakh’ in the local Yakut language. With time the bubble explodes, releasing gas,” Alexey Titovsky, director of the Yamal Department for Science and Innovation, told the Siberian Times. “This is how gigantic funnels form.”

It was unclear from satellite surveillance alone which of these bubbles posed a danger of erupting, Titovsky said. “Scientists are working on detecting and structuring signs of potential threat,” he said, “like the maximum height of a bump and pressure that the earth can withstand.”

Arctic researchers have long documented how mounds of ice, buried in dirt and soil, can erupt from the permafrost. These humps, called hydrolaccoliths or, more frequently, pingos, have cores of frozen water that migrate upward. Such pingos are typically up to a kilometer in diameter (six-tenths of a mile) and several tens of yards high.

But the smaller, methane-filled bulges do not fit the classical definition of a pingo, according to a permafrost decay expert who spoke to The Washington Post.

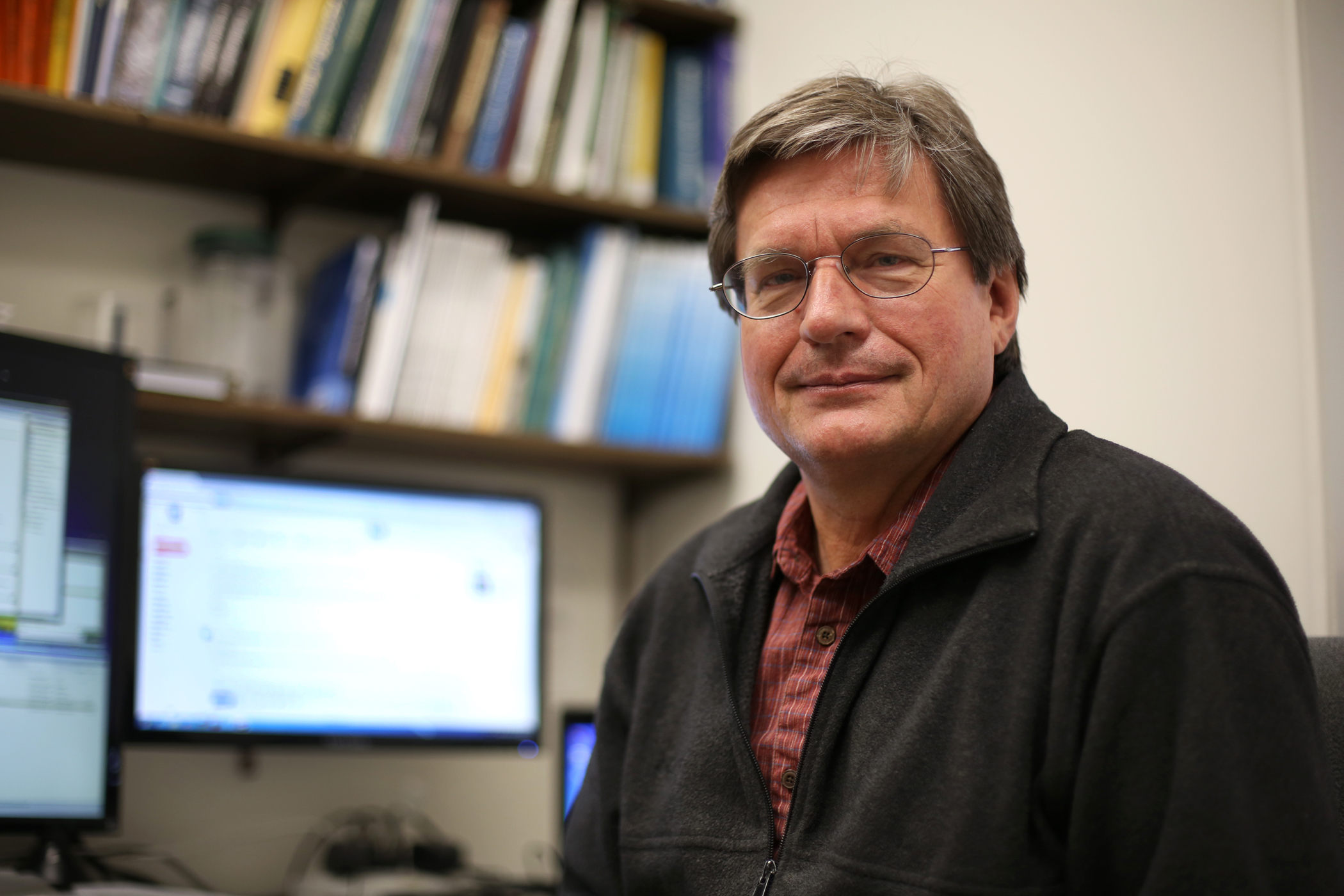

“This is really a new thing to permafrost science. It has not been reported in the literature before,” said Vladimir E. Romanovsky, a geophysicist at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. “It doesn’t mean the process is new. It means that it was never picked up and reported on.” Perhaps for want of a better name, Romanovsky called the gassy bulges “alternative pingos.”

[New permafrost map shows areas in Alaska vulnerable to thaw-induced collapses]

When researchers drill straight down into a traditional pingo, they hit the kernel of ice at the center. Coming in from the sides, drillers might discover water, close to the freezing point or possibly supercooled. But if someone were to take a drill to an alternative pingo? “That’s not good news,” as Romanovsky put it. The gas within the hill is not only under immense pressure but is quite flammable.

These humps are some 50 to 100 yards across, up to a tenth of the size of a classical pingo. Romanovsky said it was unknown exactly how the alternative pingos were formed. But he has an idea. In place of an ice kernel, alternative pingos may contain methane hydrate, the milky solid that forms when water mixes with natural gas and freezes.

“It’s definitely related to warming,” Romanovsky said. If these solid chunks warm up and decompose – and the Arctic region is heating up at a rate double the rest of the planet – the methane gas within the alternative pingo builds up.

The pressure increases to the point of collapse. Romanovsky envisioned that the process would be similar to the formation of giant pockmarks on the sea shelf, observed by scientists who study the way methane escapes from the ocean floor.

Researchers have discovered only a handful of the alternative pingo craters, which may fill with water and turn into permafrost lakes. But the craters that have been found have smooth sides – smoother, Romanovsky said, than you would expect a missile of rising ice to make. Likewise, he estimates that these mounds eject too little solid material for a gas bubble not to play a role. The bottom of one crater, explored a year after it formed, had methane gas concentrations as high as 6 percent. At that concentration, Romanovsky said, the air itself could be ignited.

(Because little is known about alternative pingos, Romanovsky said their role in other Arctic natural phenomena could be ruled out. They are not responsible for “megaslumps,” the mile-wide craters that erosion has carved with alarming speed into the Siberian permafrost, such as the Gateway to the Underworld. Alternative pingos would also not explain the recent viral video of a Russian man stomping on a small mound that shifts like a water bed. Whether the grass hid a bouncy bubble of methane gas, or was instead just water, was unclear.)

A count of 7,000 pingos, alternative included, was likely an underestimate, in Romanovsky’s view. Across the entire Arctic permafrost, he estimated there may be as many as 100,000. But he could not say how many fell into which category – a symptom, in part, of the relatively poor resolution of imaging satellites that travel above the tundra.

It is possible that alternative pingos exist in North America. The conditions seem ripe for it in the natural gas fields of Canada and Alaska. “It is just a matter of time when some of those craters appear in North America as well,” Romanovsky said. And several pingos have emerged, the scientist said, “right under the Alaskan pipeline.” If one of those bulges turned out to be an alternative pingo, he noted, that’s not good news, either.