For Norway’s next big oilfield, size isn’t everything

Norway’s Johan Castberg field is big enough to require legislative approval, but its real benefit to the industry may lie in its other attributes.

When Tejre Sørviknes, Norway’s oil minister, received plans to develop the Johan Castberg field, in the Barents Sea, on December 5, he described it as “red-letter day” for his country.

Submitting the plan on Tuesday to the Storting, the national assembly, he made it clear that he had become no less bullish about the project after spending the past four months reviewing it. If approved, he believes it would be a “milestone” for northern Norway, given its “gigantic” potential.

Objectively, this would likely be the case: The Johan Castberg field contains an estimated 558 million barrels of oil, making it the largest find to date in the Barents Sea. The development plan, drawn up by Statoil, a state-owned firm that in 2009 was granted the rights to explore there, suggests establishing production will require investments amounting to $6 billion, much of which will benefit firms in northern Norway.

[The future of Norway’s oil industry lies in the Barents Sea—but it’s far from certain]

Because of the size of the field, the legislature must approve any plans to operate there. This, combined with Statoil’s predictions that that the field will remain productive for 30 years or more, has contributed to the enthusiasm, but its size is below the major North Sea finds of the past, including the Johan Sverdrup field, which contains 2.8 billion barrels and is expected to come on-line next year.

The outsized interest in the Johan Castberg field is due as much to several other factors, one of which is that it appears to be less vulnerable to lower prices than many other offshore drilling projects, in the Arctic or elsewhere. After initially calculating that the production-cost per barrel would be above $70, Statoil now reckons it can it do it for half that.

What has also drawn the industry’s attention is the field’s location. It lies close to several smaller deposits that would not be worth developing if they had to build their own infrastructure. If Statoil’s project proceeds, nearby production at nearby fields could piggyback the Johan Castberg field’s infrastructure.

Due to the field’s remote location, Statoil proposes building a vessel that can serve as a floating production plant and storage facility, rather than build a pipeline to shore. According to the current plans, stored oil would be transferred to transport ships and sailed directly to customers. But Statoil has not ruled out getting together with the operators of the two Barents fields that are currently online to revive plans to build an onshore terminal.

A decision about whether to proceed with the Johan Castberg field is expected before summer. It is likely to pass, even if the opposition Arbeiderpartiet, the Storting’s largest party, votes against.

Arbeiderpartiet is not opposed to drilling in the Barents Sea, but it would like to see a hiatus on exploring there until it can be convinced that exploration can be done safely, though it has been suggested that the party might vote to approve drilling if it gets concessions on greener initiatives elsewhere.

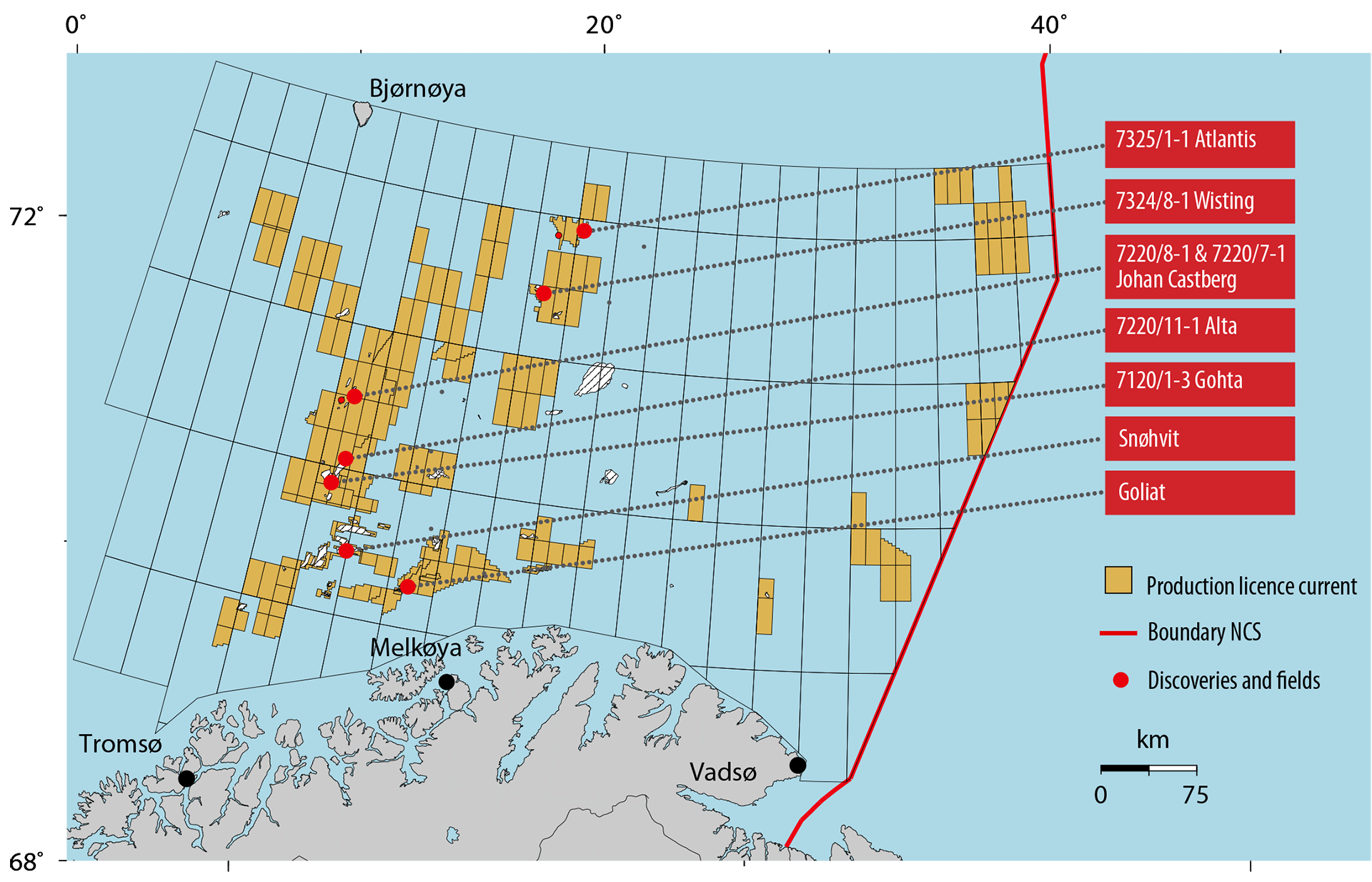

If the Johan Castberg field is approved, it will become the third active field in the Barents Sea (Snøhvit, producing gas, dates from 2001 while the problem-riddled Goliat has been pumping oil on and off since last year). The trio, though, is far from enough if the Barents Sea is to make up for declining North Sea production, according to the 2017 assessment of the state of the country’s oil industry.

[Doubts remain about Norway’s ability to earn money from Arctic oil]

In addition to making smaller fields viable, successfully developing the Johan Castberg field, which would be the northernmost Norwegian field to date, the hope in the industry is that it will invigorate Barents Sea drilling.

Conservation groups foresee the same outcome, and are asking the Storting to think carefully before doing anything that will make that happen. Most Norwegians remain unconcerned about drilling in the Barents Sea, but scepticism is growing, due in part to a high-profile lawsuit brought by Greenpeace last year, and opponents of drilling worry that opening the Johan Castberg field will make the public more comfortable with it.

Moreover, by allowing drilling in the Johan Castberg field, the Storting would lock Norway into an agreement that will result in the release of 250 million tons of carbon dioxide, according to conservationists’ calculations. Even though most of the oil and gas will be burned by others countries, opponents argue that the pollution it creates will be on Norway’s conscience.

[Statoil finds more Arctic oil]

Another concern is Eni. An Italian firm that owns 65 percent the Goliat field (Statoil owns the rest), Eni’s venture into the Barents Sea has been beset by cost overruns, accidents and numerous work-stoppages. Its problems with Goliat have led lawmakers and experts to suggest the operation might never be profitable.

Eni is a 30 percent partner in the Johan Castberg field, and opponents fear what its involvement will mean for the project.

“Our fear,” says Silje Ask Lundberg, the chair of Naturvernforbundet, a conservancy, “is that we haven’t learned anything from Goliat, and that means this project will turn into an exercise in defects, cost overruns and serious accidents.”