For Northern destinations, spring is a season of discontent

Springtime in the North offers a glimpse of what is at stake for communities if they fail to come to terms with mass tourism.

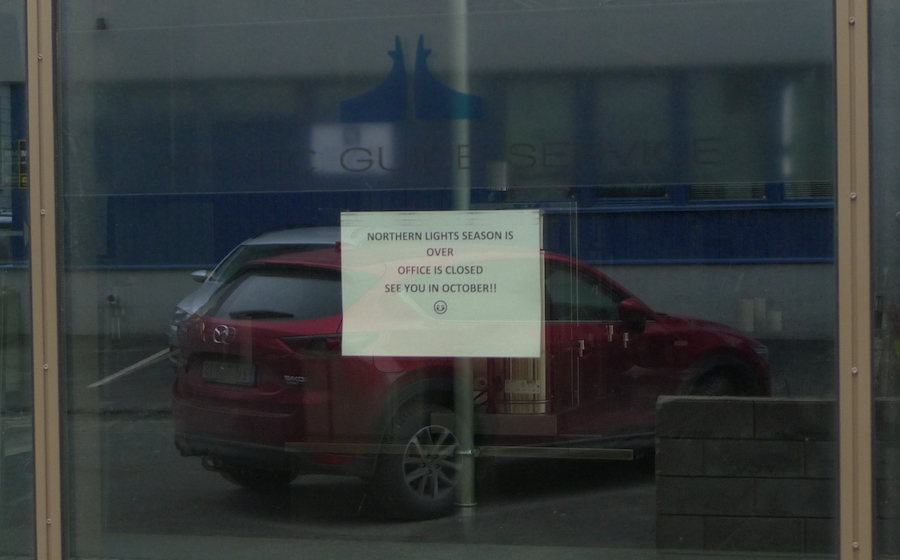

To get an idea of what Tromsø, Norway, might look like without tourism, visit on the first day of May. A public holiday during the depths of the off-season for visitors, the streets are desolate. The few stores that are open are mostly empty. Tour offices, each prominently displaying pictures of the Northern Lights, are closed for the season, which only adds to the run-down appearance.

The image stands in contrast to Tromsø during peak weeks in January, when Northern Lights tourists and others looking for what outfitters call “soft adventure” —winter activities, such as tobogganing, that are thrilling, but not really dangerous — drive hotel occupancy up to 95 percent or higher.

Around this time of year, though, about a third of rooms are filled, and there is a good reason why.

“This is the worst time of year to visit. There’s nothing to do, and, instead of the Northern Lights, this is your view,” says a taxi driver, gesturing out a dust-covered window towards piles of blackened snow.

Like other northern regions, Tromsø has seen rapid growth in the number of visitors in recent years. Since 2007, the number of overnight stays has doubled, to 800,000. In the first quarter of this year, which covers most of the December-April high season, the number of foreign visitors rose 20 percent, bringing the number to over 100,000.

Residents say they welcome the contributions tourism make to the city’s economy (for Northern Lights tours alone, this figure may exceed a billion kroner, or $120 million, annually) but with a population of 75,000, visitors are a constant presence. As the taxi driver puts it, “they are unavoidable when I am at work, which I love. And they are unavoidable on my day off, which I could do without.”

Such sentiment may suggest that attitudes in Tromsø are close to the sort of turning point that has caused residents in the most visited parts of Iceland, and in particular, Reykjavík, its capital, to push back against the industry, and the effects its runaway growth has had on labor, housing and infrastructure. Other complaints include the general unease that comes with seeing unfamiliar cars parked outside homes, or people going to the bathroom near homes.

Tourism officials in Iceland have long recognized that the country could become a victim of its own popularity, and sought to implement measures to ease its impact. But the number of travelers has increased unabated, and in 2017 the number surpassed 2 million, or six times the country’s population (although some doubt has been cast on whether official counting methods have overstated this number), and there are signs a limit may have been reached.

The most recent warning signal was raised in April, when a report documented increasing dissatisfaction with the number of visitors was presented to the Alþingi, the national assembly. Amongst its findings: 40 percent of residents in the most visited areas feel there are too many visitors and want measures taken to limit their numbers.

Perhaps more worrying, visitors are also becoming dissatisfied, especially with worn and overcrowded conditions at the most popular areas.

The connection between unwelcoming hosts and unhappy guests, should come as no surprise, according to Chris Hudson, the chief executive of Visit Tromsø, which coordinates the region’s tourism businesses. He points to Venice as another example cities should try to avoid. There, locals, feeling overwhelmed by visitors, have turned against the industry.

“That,” he said this week during a seminar hosted by UiT/The Arctic University of Norway (and described in further detail in this week’s Week Ahead), “is the worst thing you can have happen to your destination.”

[Tourism in the Arctic: Keeping it authentic]

Dissatisfaction in Tromsø has not reached the same point, neither amongst residents nor visitors, and Hudson believes this is partly because the tourism industry’s efforts to build up Tromsø as a destination has residents, nor visitors, in mind.

“We invest first in the things that are important to locals, and then we add a kind of extra capacity to accommodate the tourists who come here,” Hudson said. He highlights public toilets as an area Visit Tromsø focuses on.

Having a good reputation amongst potential travelers is not enough, though. While places like Tromsø work hard to be welcoming places to visit, the rise in the number of visitors is, according to the Commerce Ministry, due in large part to things the industry has little control over, such as a favorable exchange rate for Europeans and North Americans, concerns about terrorism in traditional winter destinations and a general increase in the number of travelers.

Nor is it enough just to be a good place to visit, or even a good Arctic place to visit. Tromsø is far from the only destination pushing its Arctic location as a main selling point. In Scandinavia alone, Sweden, Finland and other parts of Norway all offer a similar product that is equally easy to reach. Add Iceland, Greenland and Russia, and suddenly the market for Arctic destinations easily reachable from Europe becomes a busy one.

[Russia lays out plans to boost Arctic tourism]

With so many similar destinations, local tourism authorities must identify what it is that makes them stand out, a process known in the industry as differentiating. Tromsø, for example, can offer soft adventure, but, as a city, it should not forget that it can offer visitors a level of culture and urban comfort that places like Greenland cannot, according to Ilan Kelman, of PRPI, a London-based think-tank working on polar issues.

“Many are seeking the uniqueness the Arctic offers, but many are not,” he said.

Differentiating gives potential visitors a reason to choose one destination over another, but, according to Maria Kjellsson, a Swedish hotelier, it can also give people a reason to travel in the first place.

In January during Arctic Frontiers, a big annual conference in Tromsø, she described how her work developing seafood tourism on the coast of western Sweden was helping her hotel and other businesses in the area stay busy beyond what had once been just a short, six-week summer season.

“No one doubted that we had quality shellfish in the autumn, but the marketing people we spoke with told us the grey weather at that time of year would scare visitors off. What we found, though, was that, packaged right, the bad weather was the selling point,” she said.

The marketing term they came up with to sell damp, overcast autumn weather was ‘grey-weather sensualism’, which, according to Kjellsson, sought to create an atmosphere that “embraced what the area had, rather than inventing something unauthentic”.

For Tromsø, following suit may, unfortunately, require embracing blackened snow.