We need to fill the gaps in Arctic research before a crisis strikes

OPINION: A major Arctic disaster will lay bare the gaps in Arctic knowledge and safeguards. The time to fix the is now.

In the event of a major shipping or oil spill disaster, Arctic nations will face unprecedented environmental and humanitarian challenges.

A cruise ship fire in a remote portion of the Arctic Ocean, an oil tanker shipwreck or a major accident on a drilling platform could have severe consequences for the entire region.

Are the international management, monitoring, scientific, and legal agreements in place to reduce the chances of disaster and provide for an effective response?

Not yet, according to researchers who have looked at some key elements of this complex regulatory challenge and found weaknesses.

Their work is found in a section of the 2018 edition of the Arctic Yearbook, an annual compilation of the latest interdisciplinary Arctic research.

The risks and impacts from building and operating offshore facilities in the Arctic have yet to be fully examined.

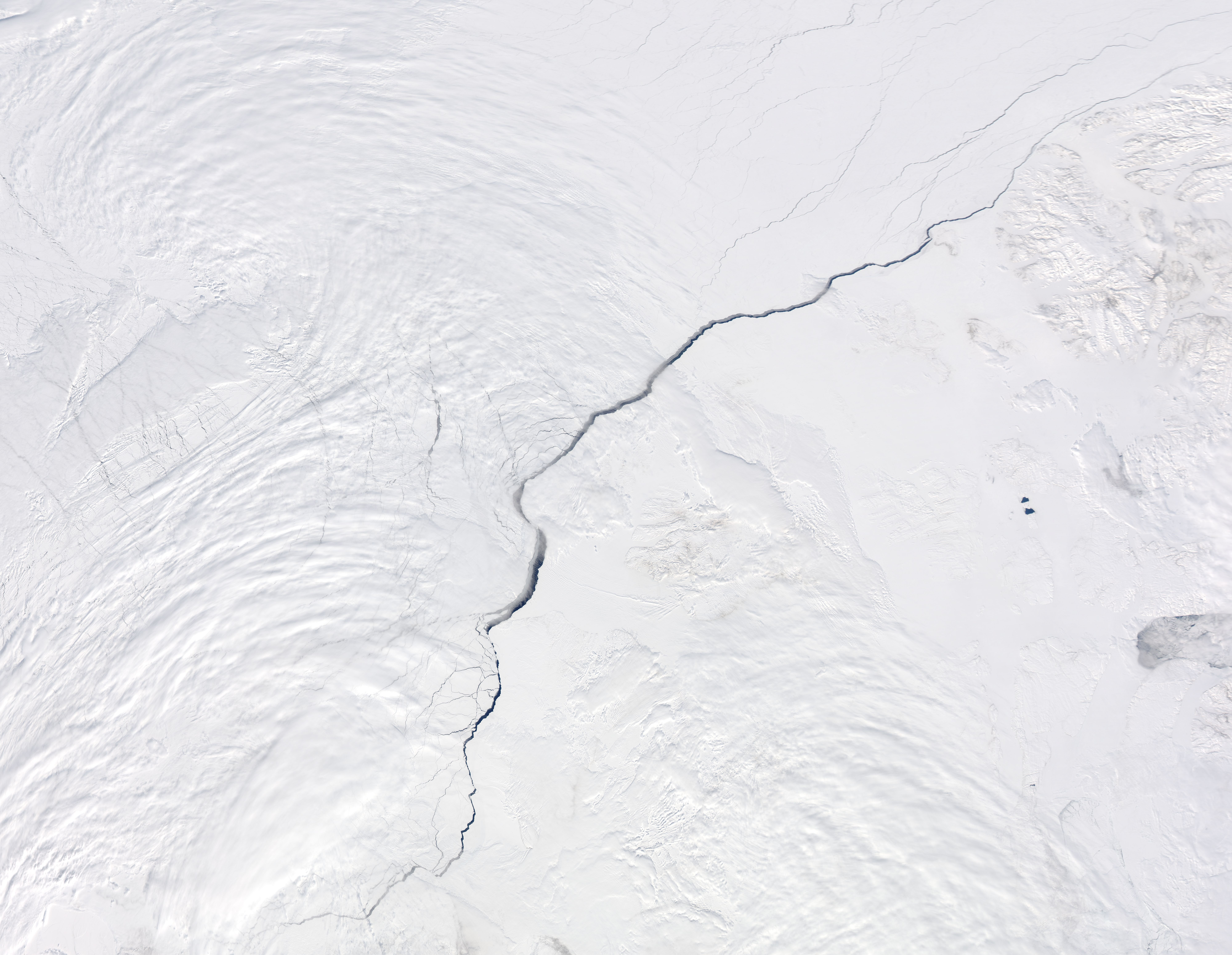

But with climate change impacting the Arctic at an accelerating rate, the level of international interest in recreational travel, cargo traffic and resource development is rising quickly.

The increased activity means a greater risk of accidents, and if the Arctic is unprepared, it is because it wasn’t long ago that year-round ice served as an impenetrable barrier to commerce.

There are multi-national agreements in place on civil liability, environmental protection, scientific research, monitoring and other issues, but most were not conceived with the Arctic in mind.

Weather that is often unforgiving, the lack of local infrastructure and the long distances from major population centers will create nightmares for all of those called upon to deal with Arctic disasters.

Oil spills are one of the most serious threats as development proceeds and the existing rules on civil liability are a weak spot.

“Civil Liability regimes are not drafted in light of the Arctic’s unique environmental conditions and risks; therefore, they require adjustments according to the Arctic shipping realities that we face today,” wrote Ilker Basaran, a graduate student at the International Maritime Law Institute.

Meanwhile, the newly adopted Polar Code for ship traffic calls on vessels to be prepared for five days of self-sufficient operations in case of trouble.

“However, the need for additional capacity for the crew to be able to operate on their own with firefighting for a longer time period is bad weather conditions, is not included in the Polar Code,” three researchers from Nord University said in a review of response challenges for maritime emergencies.

The code also does not have “obligatory education and training as to emergency contingencies and response in Arctic waters.”

“We argue that role flexibility, re-planning capability and authority delegation are critical prerequisites for an efficient crisis response in the Arctic,” said Natalia Andreassen, Odd Jarl Borch and Emmi Ikonen of Nord University in Norway.

Regarding oil spills, there are flaws in international agreements that put the Arctic at risk for damages from future oil and gas spills.

“Although there is a substantial amount of information available on the environmental effects of hydrocarbons in the marine environment, relatively few impact studies have been carried out on truly Arctic species,” Elizabeth Kirk and Raeanne Miller wrote in an examination of the science and law related to oil and gas activities.

Oil spills in the Arctic, even those that are relatively small, will last longer and be more difficult to deal with than those in more southerly regions.

Kirk, a professor of international law at Nottingham Trent University, and Miller, a post-doctoral researcher in marine energy at the University of the Highlands in Scotland, said that existing agreements on pollution and the marine environment need more attention.

“Combined with the fact that Arctic food chains are comparatively short and dependent on key species, pollution, even comparatively low level operational pollution, could have severe impacts on the functioning of the Arctic ocean ecosystem,” they said.

Oil is more viscous in colder water and it degrades at a slower rate.

These called for a “precautionary approach to further oil and gas activities in the Arctic.”

Kirk and Miller cited the recent agreement for a moratorium on high seas fishing in the Arctic as an example of international cooperation prompted by a need for more research.

While the Arctic Yearbook papers cover only some of the development challenges expected with climate change, the scholars make a convincing case of the work that needs to be done.

The gaps in monitoring, environmental research, industrial safeguards and multi-national agreements will be obvious after a major disaster in the Arctic.

Rather than wait for the recriminations that will follow, the time to act is before the crisis happens.

Columnist Dermot Cole lives in Fairbanks and can be reached at [email protected].

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by ArcticToday, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary (at) arctictoday.com.