Local Arctic leaders in North America hope closer ties will boost development in the region

Leaders of sub-national governments of the North American Arctic hope that better cross-border ties will help them develop the region—even as a new report warns it's falling further behind the European Arctic.

Despite their differences, the North American Arctic’s five regional governments find there’s one problem they all share: They often get a raw deal from their national governments.

To counter that, government leaders from Alaska, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Greenland have been looking for ways to build a common front, work they continued earlier this month at the Northern Lights trade show in Ottawa, at an event sponsored by the Centre for International Governance Innovation, or CIGI, a think-tank based in Waterloo, Ontario.

“If the sub-national governments are able to get together and articulate a vision of what development might look like, and what infrastructure support that might mean, then your leverage to drive that agenda is much more powerful,” Jennifer Spence of CIGI told Nunatsiaq News.

At the same time, Spence and John Higginbotham, another CIGI fellow who is also a professor at Carleton University, released a paper that contains a dire warning: the North America Arctic is falling behind the rest of the circumpolar world.

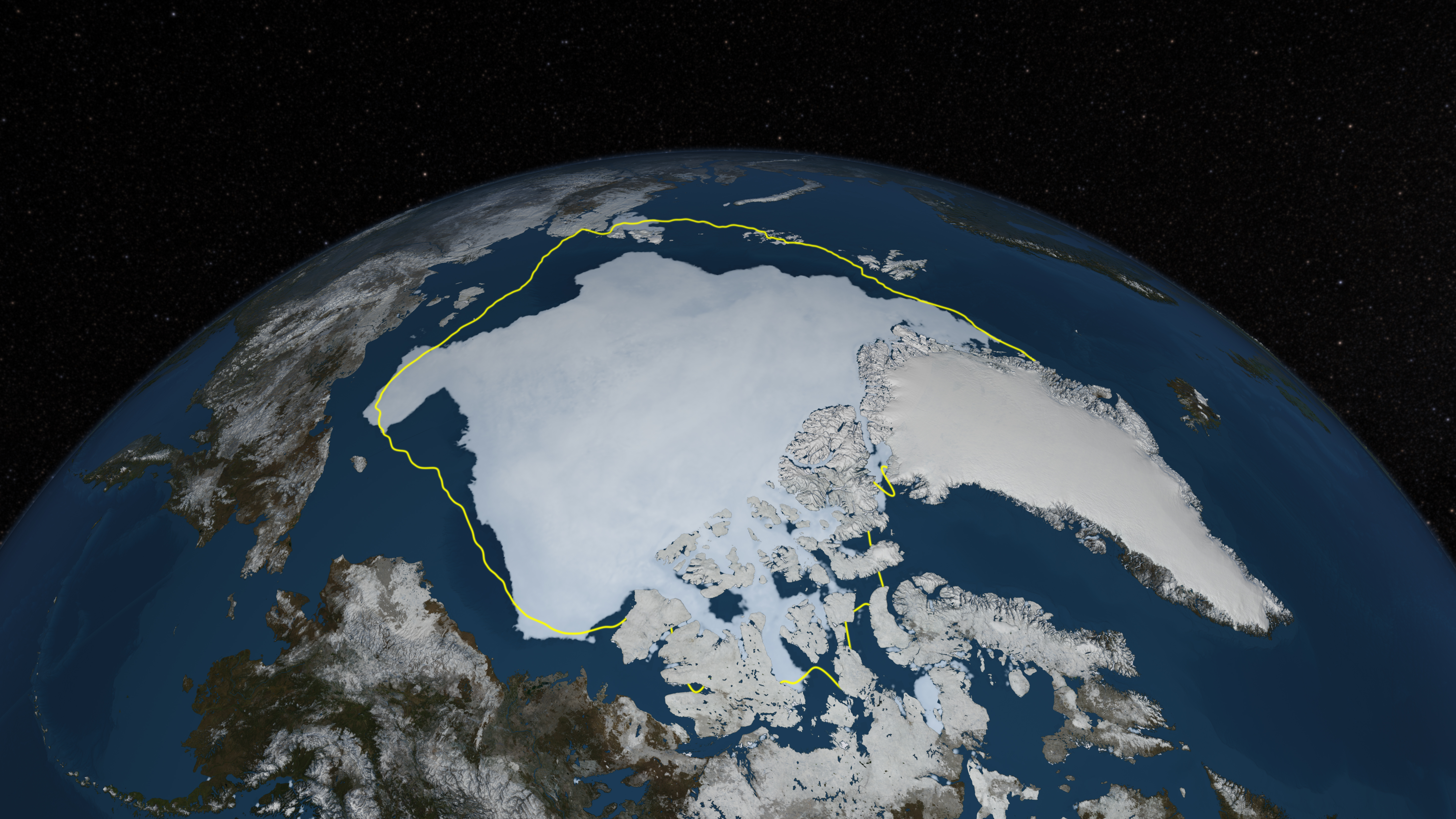

They point out that there are “two Arctics.” One is the prosperous, well-developed European Arctic of Norway, Sweden, Finland and to a lesser extent, Russia, regions that benefit not only from a more favorable climate, but more consistent national policies.

The other is the North American Arctic.

“In contrast, the NAA region — Alaska, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Greenland — has harsher and more extreme environmental conditions, spotty or non-existent infrastructure, and is composed primarily of small, remote communities with economies that have suffered from boom-and-bust development,” Spence and Higginbotham said.

“Policies about the region are often set by default, far to the south in Washington, Ottawa and Copenhagen, where decisions are dominated by international interests poorly aligned with the needs and interests of the people of the NAA,” the report said.

Those problems, rooted in a harsher climate, are made worse by erratic national policies and indifferent public opinion in the countries they’re a part of.

“Because the understanding of the issues in the North is so weak in the South, that’s all the more reason for the subnational governments to assume a leadership role in articulating what the policy needs of the North are,” Spence said to Nunatsiaq News.

“The more they can speak with a coherent voice on what the issues are — not necessarily agreeing on what the solutions are, but what the issues are — that’s all the more power they will have to influence federal policy.”

For the N.W.T., it’s about resource development

For N.W.T. Premier Bob McLeod, the need for strategic infrastructure is a top priority and he said the federal government must step up to help provide it.

“Northerners need a plan for the social and economic development of the Northwest Territories, and Canada needs to be part of that, including making concrete commitments to strategically invest in areas that will create the greatest benefit for northerners, ” McLeod said.

McLeod pointed out that more than half of the N.W.T.‘s 19 MLAs are Indigenous people, as are five of the N.W.T. government’s seven cabinet ministers, and that the territorial government has a good working relationship with the territory’s regional Indigenous governments.

That means the creation of a strong, thriving economy in the N.W.T. “is a crucial part of a successful model for Indigenous reconciliation that could serve as a guide for the rest of the country,” McLeod said.

And he said that for the N.W.T., resource development — minerals, oil and gas — is the key to creating that strong economy.

That includes many of the minerals that are highly sought after in the emerging green economy by makers of batteries, solar panels and wind turbines: cobalt, gold, lithium, bismuth and rare earths.

But following the global financial meltdown of 2007, the N.W.T.‘s economic output shrank and has never fully recovered, McLeod said.

In 2007, the N.W.T.‘s annual GDP stood at $4.5 billion, but by mid-2016 stood at only $3.7 billion, he said.

Fixing that means Canada must make more nation-building investments in energy, communications and transportation, including an eventual all-weather road through the Slave Geological Province from Yellowknife to Nunavut’s Grays Bay on the Arctic Ocean.

“We would like to see us connect with the Nunavut Grays Bay road proposal. I think that would be worth pursuing,” he said.

He joked that one day he would like to get into a car in Yellowknife, drive to a port at Grays Bay, hop aboard a cruise ship and then sail to Tuktoyaktuk and from there, drive to a casino in Dawson City, Yukon.

Nunavut wants devolution, infrastructure

Nunavut Premier Paul Quassa confirmed with Nunatsiaq News that his new government fully backs the Grays Bay road and port proposal, which was first put forward by his predecessor, former premier Peter Taptuna, in partnership with the Kitikimeot Inuit Association.

Quassa, commenting on a common theme of the discussion, told Northern Lights delegates that to counter the north-south flow of power, money and information, northern governments need to build on east-west relationships.

“In the old days it was always north-south, but all of us northern leaders recognize that there is much more need for west-to-east and east-to-west relationship building,” Quassa said.

To that end, Quassa said he looks forward to hosting the next northern premiers’ meeting this May in Rankin Inlet.

“This forum is very important for many reasons, including discussing issues of common interest and concern, and to develop made-in-the-North solutions. I think that is so vitally important,” Quassa said.

One example of that is the new Arctic policy that the federal government is developing and it’s vital that northerners play a major role in shaping it, he said.

And he said that despite their small population, the people of Nunavut can achieve great things.

“Our population is just 36,000, less than 40,000, very small, but we had the courage to change the map of Canada… that shows the rest of the world that you don’t have to be large in number to change something of your country,” Quassa said.

He also said a devolution agreement—to transfer control over public lands and resources from Ottawa to the Nunavut government—is a key to Nunavut’s future political development.

“That is the key to getting more control and more say within our territory,” Quassa said.

As for Nunavut’s priorities, Quassa said they are the same as those that led to the signing of Nunavut Agreement was signed: “our people, our land and our culture — inuqutivut, nunavut, iliqusivut.”

To make that possible, Nunavut needs roads, ports and fibre-optic communication links, Quassa said.

Greenland moves forward on marine transport

Suka Fredriksen, the minister of independence, foreign affairs and agriculture in the government of Greenland, said her country wants more cooperation with the rest of the North American Arctic, but right now, there isn’t enough of it.

She pointed out that Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, is only 500 miles away from Iqaluit and that Qaanaaq, in northwest Greenland, is only 200 miles away from Grise Fiord — less than the distance between Ottawa and Toronto.

“Mindsets have to be changed,” Fredriksen said, pointing out that there are few trading links between Greenland and Arctic North America.

She said that could change with a new joint-venture agreement between the Royal Arctic Line, the Greenland government-owned marine shipping company and Eimskip, a Icelandic shipping firm.

Under that deal, those companies will ship goods directly to and from ports in Europe and North America, and make use of an expanded container port at Nuuk, Fredriksen said.

Under that plan, Greenland would be directly linked with Iceland to and from ports in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Labrador and Boston, she said.

“Once the container port in Nuuk and the joint venture agreement between Royal Arctic Line and Eimskip is fully implemented, Greenland will be physically linked to North America for trading goods at a level never experienced before,” she said.

This meeting of the five northern leaders is the second such gathering—the first was held in March 2017, in Washington, D.C., also at the behest of CIGI.