Keep mining policy consistent, economists tell Greenland’s leaders

A long-term, stable regulatory environment is decisive if the country is to be able to count on growing its mining industry, annual economic report warns.

To a large degree, mining activity in Greenland is determined by developments in the global economy, but the country’s legislators can go a long way towards reassuring the industry that it is a safe place to invest, Økonomisk Råd, a panel of independent economic advisors to the government, says in its annual outlook.

“Mining is decisive for expanding the economy. For the industry to grow, there must be stable policies in the long-term,” the report says.

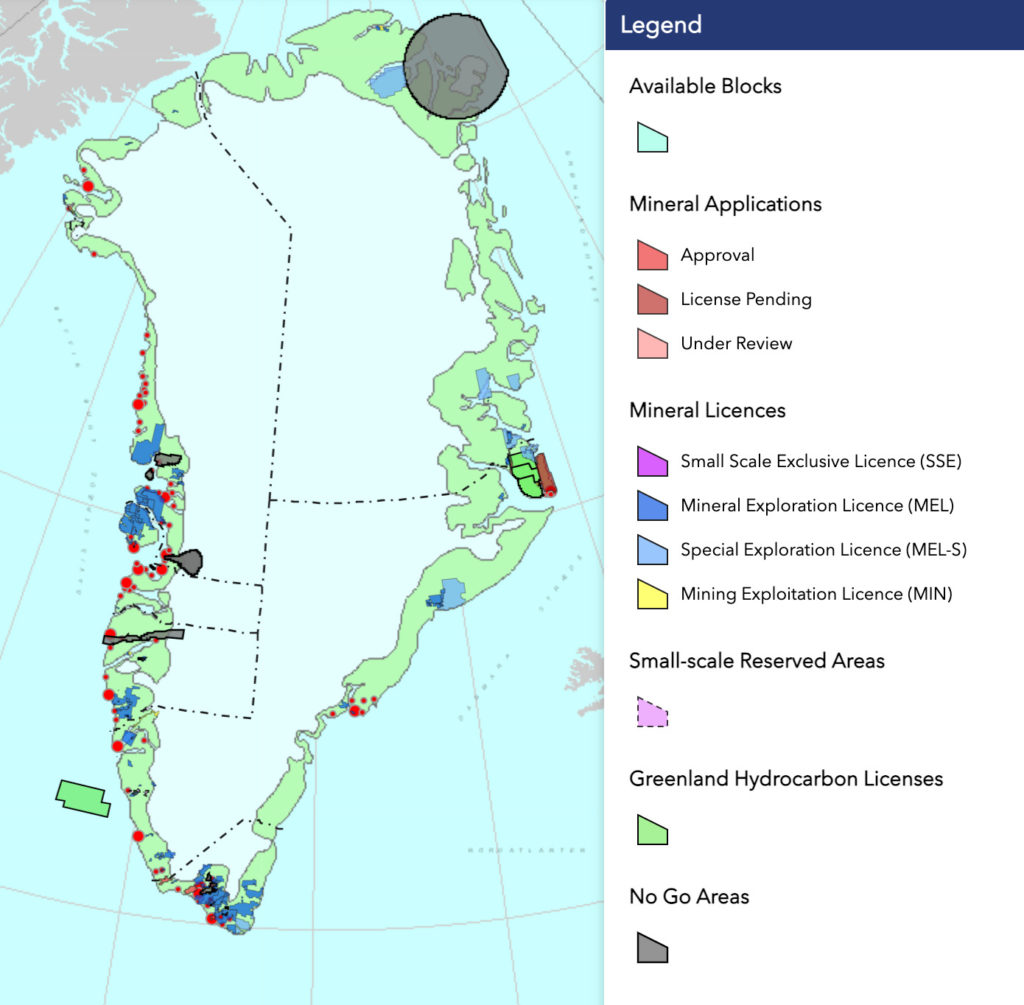

Investments dipped in 2020, but the decline, according to Økonomisk Råd, can be pinned on COVID-19. During the previous years, mining activity in Greenland grew steadily, and the country saw two mines begin operation, the first since the industry fell silent there in 2013. Seven more are closing in on final permission to come on line. With another 70 active exploration licenses, this number will all but certainly grow.

Price developments, expected to dip in 2022 after surging by as much as 30 percent in recent years on higher demand for metals needed for modern batteries and other high-tech equipment, may put a damper on growth in the short-term. But, even during periods of high demand, Greenland risks scaring off mining firms by not providing them with a clear message about the future of the industry there, Økonomisk Råd warns.

“Uncertainty has a negative effect on investments,” it wrote.

This, it points out, is particularly true in a place like Greenland, where the lack of previous activity requires firms to make large, long-term investments.

The recent growth of Greenland’s mining industry has defied what Økonomisk Råd describes as a “worrisome” decline in the country’s ranking in the Annual Survey of Mining Companies, which ranks mining provinces against against each other. The drop has been particularly noticeable when it comes to opinions of Greenland’s mining policy; after reaching a highpoint in 2014, when it finished in the ranking’s top 25 percent in this category, it found itself in the bottom half of the 77 provinces that were rated last year.

The survey, Økonomisk Råd admits, must be taken with a grain of salt: It is based on the subjective input of a relatively small number of companies. Nevertheless, the report highlights two changes that Økonomisk Råd suggests could affect the industry’s interest in making further investments — an end to oil exploration announced in June, and a ban on uranium mining that is expected to be presented to the national assembly this autumn.

The change in oil policy, it notes, comes after the previous government, in 2020, unveiled a plan that was aimed to reinvigorate interest in exploration. The proposed uranium mining ban, meanwhile, would amount to a reimplementation of a ban that the national assembly repealed in 2013 by a single vote and comes as the controversial Kuannersuit mining project, which would entail uranium extraction, is nearing a final decision about whether it will be permitted to begin operation after more than a decade in development.