In-home water and sanitation systems offer alternatives to serve remote Alaska villages

Faced with daunting gaps in water and sewer systems, some Alaska Native communities are thinking small.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted health disparities long endured in many Alaska Native villages. Now, informed by the lessons of the pandemic, Alaskans are making investments and using research and design to build a healthier future in rural and remote areas. This is the second in a series that tells their stories.

In rural Alaska, thousands of residents lack running water and flush toilets, an absence that contributes to the spread of contagious diseases. This lack of sanitation infrastructure has disproportionately harmed Alaska Natives.

But now, the Indigenous people of rural Alaska and the environmental, and housing experts who work with them, are increasingly taking a new, creative approach to that big health problem: They are thinking small.

Rather than wait for costly municipal-scale piped-water and wastewater systems to be built, some parts of rural Alaska have turned to microsystems that serve individual homes.

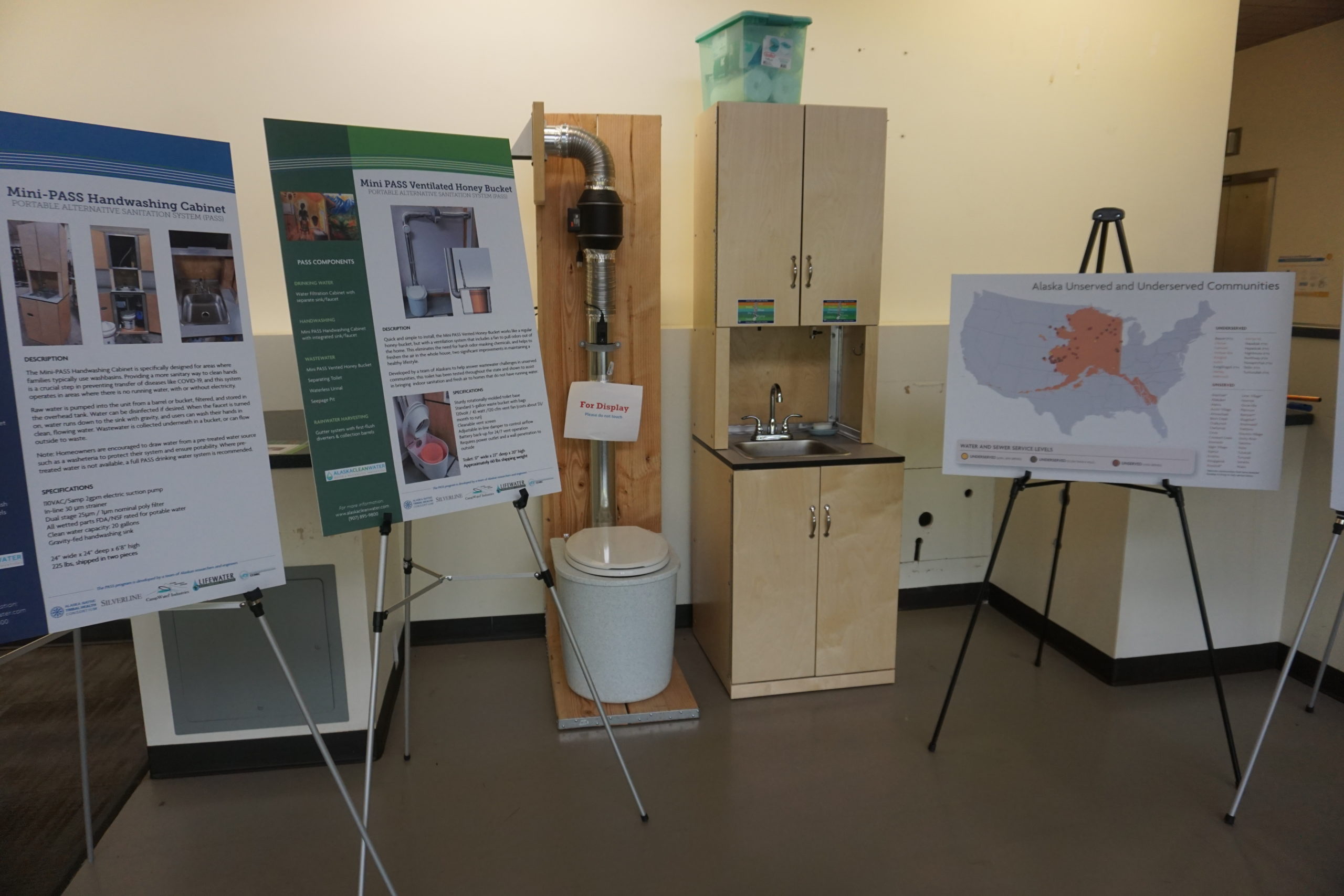

The best-known of these systems is the Portable Alternative Sanitation System, or PASS, developed and distributed by the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. It is aptly named “because it was engineered in response to filling that gap,” said Jackie Qatalina Schaeffer, community development manager for the consortium.

PASS consists of a water container that uses gravity to feed into a sink, with two layers of filtering and chlorination to achieve drinking-water quality. It includes a catchment system to collect rainwater, thus reducing the need for burdensome collections.

[For some Alaska villages, the lack of modern water and sewer service means more health risks]

On the waste side, it has a dry toilet that separates liquids for ground disposal through a drain line to a seepage pit outdoors, along with a waterless urinal that also drains to the seepage pit. There’s a continuously operating fan to vent bad smells out.

Materials to build the PASS units cost about $50,000 per house, versus the $200,000 to $500,000 it would cost to connect a rural Alaska house to a fully operating piped water and sewer system, Schaeffer said.

As Schaeffer sees it, the PASS is an intermediate step bridging a cultural mismatch that is a product of Alaska history.

In many Alaska Native traditions, she said. people did not have significant human waste disposal accumulations associated with their homes because their homes were on the move. “They traveled with the food resources,” she said.

Enter the American system of imposed permanent settlement and a matching, if low-tech, waste-management system: the honey bucket, the five-gallon plastic bucket lined with trash bag and topped by toilet seats that are used as low-tech toilets.

“When they settled and brought that waste into a confined area, that’s when the honey bucket was introduced. Because that’s a very Western thing. It’s not traditionally what Indigenous people did. Their waste wasn’t part of their house,” Schaeffer said.

The PASS concept is “looking at how do we fill that gap from Western infrastructure like the honey bucket that isn’t so healthy and create healthier habits around that, so that eventually they get pipes and then you have that healthy system,” she said.

The first PASS units were installed in the Iñupiat village of Kivalina in 2014. It is an especially fitting location for a sanitation system that is portable: The village, perched on a coastline that is eroding quickly as sea ice retreats and permafrost softens, is one of the threatened Alaska communities that is planning for a full relocation to safer, higher ground farther inland.

Now the COVID-19 pandemic has made sanitation problems more urgent — and spawned the development of an even simpler and cheaper unit, the Mini-PASS.

The tribal health consortium commissioned and distributed 100 Mini-PASS units to 10 unserved villages. Distribution, completed in four months earlier in the year, was a direct response to COVID-19 emergency, Schaeffer said.

“With COVID, obviously, washing your hands is important. So the whole point was getting them clean water to wash their hands,” she said.

Essentially a handwashing station, the Mini-PASS is a scaled-down PASS, starting with the price tag: $8,000 to $10,000 for materials.

Its water tank holds 20 gallons, enough for 100 20-second hand washings, Schaeffer said. That compares to the 50- or 100-gallon tanks used in the full PASS units. Water in the mini-PASS goes through a single filtration system that’s less sophisticated than the double-filtration system used in the full PASS. It flows through the unit’s sink to a bucket below that must be hauled out.

Unlike the full PASS, which replaces the honey bucket with a dry toilet, the mini-PASS leaves the honey bucket in place. However, it does include the PASS system’s ventilation system. To Schaeffer, there’s an important benefit: “eliminating the VOC exposure from Pine-Sol and Lysol trying to mask the smell of human waste.”

The volatile organic compounds emitted by those cleaners are linked to respiratory diseases, headaches and other problems, she said. “And that has been — for decades — in rural Alaska,” said Schaeffer, who is from Kotzebue and did not have in-home piped water and sewer until she was in middle school. “I grew up with VOCs, my mother did, my grandmother did.”

There have been some glitches and shortcomings in the Mini-PASS project. Users must still haul water, and some would have liked the units to have small water heaters. And the men involved in the original design failed to notice a problem that had to be corrected – the honey-bucket platform was perched too high.

“When I initially sat on the toilet, my legs dangled,” Schaeffer said. “If they can’t sit comfortably, we’re going to have a problem”

The PASS and mini-PASS technology are products of a partnership.

The water portion is designed by a company called CampWater Industries, based in Delta Junction, Alaska, and in business for more than 20 years. It has a history of serving industrial users with remote camps, from tiny mining sites to North Slope oil sites with hundreds of workers. In its PASS work, the company has adapted it expertise for industrial clients to the needs of individual homeowners. And it has established or help establish service well outside of Alaska — in other Arctic regions such as Greenland and Canada’s Northwest Territories, and also far to the south, in Colombia, and most recently, Kenya.

The sewer part was designed by Lifewater Engineering Co., a Fairbanks company that also has experience with larger industrial and municipal clients. For distribution and servicing of PASS systems, Lifewater and CampWater, which handles unit manufacture, have established a limited partnership called Silverline.

The air ventilation system was designed by the Cold Climate Housing Research Center located at the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus. The Cold Climate Housing Research Center and ANTHC were the prime movers of the project, and they pulled in the other partners based on past relationships. For example, Jack Hebert, the founder of the Cold Climate Housing Research Center, called on CampWater founder Jon Dufendach, who had previously designed a water-filtration system that removed natural arsenic at one of Hebert’s housing projects.

Dufendach is excited about distributing PASS-type technology as widely as possible, including to faraway places like Africa and South America. “There’s a passion about correcting the problem and making a better life there,” he said.

For Alaska, the mini-PASS can deliver a quick fix, Dufendach said. “So many of the homes out there in the bush, just frankly, don’t have the floor space for a full PASS system,” he said.

The PASS and mini-PASS are not the only in-home systems.

Other household-scale technologies have resulted from the Alaska Water and Sewer Challenge, an Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation program launched in 2013. It has since become an ongoing department function, with funding from the Environmental Protection Agency and the state legislature.

Twenty projects were originally entered in the competition, which awarded funding for further research and development. Those 20 were winnowed to three by 2015.

The top-ranked project — now poised for field testing — is an in-home water recycling system created by a University of Alaska Anchorage team. The system, which was first tested at a mock cabin set up in a UAA parking lot, is designed to provide a daily supply of 15 gallons of washing water per person, well above what is currently used. It uses skimmers, filters, air pumps and ultraviolet light to clean the water as it cycles back through the system. The team is now working on a plan to install the system in a UAA dorm so that it can be used in real life.

Increasing wash water availability is critically important in rural Alaska, said Fatima Ochante, the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation Water and Sewer Challenge project manager.

In unpiped communities where residents are burdened with the task of hauling water, they use far too little, Ochante said. According to various studies, some villagers use less than 2 gallons a day per person, far less than the World Health Organization guidelines of more than 13 gallons a day, she said.

“Folks end up rationing the quantity of water that they use and even reusing it in an unsafe way,” she said. “We needed to come up with a prototype or a system that distributes enough water at an affordable price.”

The technology as developed by the UAA team allows non-potable water to circulate nearly 40 times before being discharged as concentrated greywater, said Aaron Dotson, the engineering professor leading the project. The cabin prototype required weekly inputs of 30 gallons of water — with a variety of sources possible, such as rainwater or river water — and produces 30 gallons a week of wastewater to be deposited outside.

The recycled water, though it is processed to drinking-water standards, is not for drinking or cooking; potable water is circulated in a separate and smaller system that feeds into sinks.

The Water and Sewer Challenge produced other technologies, too.

Participants developed an alternative dry toilet system that separates urine and feces and are designed specifically for permafrost areas where treated wastewater cannot easily percolate into the ground. Dozens of units are already in use in two communities — Kongiginak, a Yup’ik village of about 400, and Arctic Village, a Gwich’in village of about 200 And villagers in Diomede, with fewer than 100 people and a location on a tiny island in the middle of the Bering Strait, are interested in installing 30 units, Ochante said.

Alaska has a particular need for household-scale water and sewer technologies.

Like the rest of the Arctic, the state is warming faster than almost any other place on the planet, and the resulting thaw, flooding and other acute impacts take a toll on all kinds of infrastructure, including water and wastewater systems. Arctic coastlines are taking a particular pummeling, with more open water meeting thaw-softened coastal bluffs to speed erosion.

Partial relocation to more stable ground has already started in some places. That includes the eroding Yup’ik community of Newtok, which is shifting to a new site called Mertarvik. Homes have already been built there, complete with new PASS units in each.

The PASS approach is a good fit for relocation needs, Schaeffer said.

“The hope there was if we have to relocate communities like Kivalina or Newtok that we go from PASS to pipes,” she said. “In order to get piped service, they have to have a majority of the community living in the new location, so there’s always going to be that gap.”

But what if tricky permafrost conditions, ultra-remoteness or other physical constraints make piping nearly impossible? There is yet another technology approach: individual wastewater treatment systems such as those in use at the Cold Climate Housing Research Center in Fairbanks.

Those systems are in operation at the center’s four-house “sustainable village” living laboratory on the edge of the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus. All the houses are occupied, and behind each is a big black box with a long pipe extending into the back yard — a household-scale sewage treatment plant. When toilets flush, contents go into the box, solids are filtered out and the liquids, after going through a series of treatments, trickle out the end of the pipe as clean water falling on the ground.

It is an approach that needs to be in the mix, Hebert said.

“The ideal thing is piped water and sewer. But in many regions of rural Alaska, you’re never going to get piped water and sewer,” he said.

Support for this reporting came from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the Annenberg Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California.