In Alaska’s record-warm year, the heat-up was most dramatic in the Arctic

The lack of summer sea ice near Alaska's coasts was one big factor driving the record-setting heat.

Alaska just completed its warmest calendar year in nearly a century of records, and the warming was most extreme in the state’s Arctic regions, climate specialists reported.

Overall, the statewide temperature averaged 32.2 degrees Fahrenheit, the first time that a calendar year’s average in Alaska was above the thaw point, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

[Alaska had its warmest year ever in 2019, a new report finds]

The formal call was made in a national report issued on Jan. 8 by NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. Alaska’s statewide average temperature was 6.2 degrees Fahrenheit above the long-term average and 0.3 degrees Fahrenheit above the previous calendar-year record, set in 2016.

The 2019 mark is part of a long-term trend, climatologists said.

The four warmest Alaska years have occurred in the last six years, NOAA’s report said. And every year since 2014 has been among the top-10 warmest Alaska years, said Rick Thoman, a climate scientist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Nine of the top-10 warmest Alaska years have occurred since 1990, and all of the 10 coldest years were at least 44 years ago, he noted.

While the warming was widespread — eight of Alaska’s 13 regional climate divisions regions posted their warmest year in 2019 — it was extreme on the North Slope, Thoman said. There, the annual average was 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit above the previous record, he said.

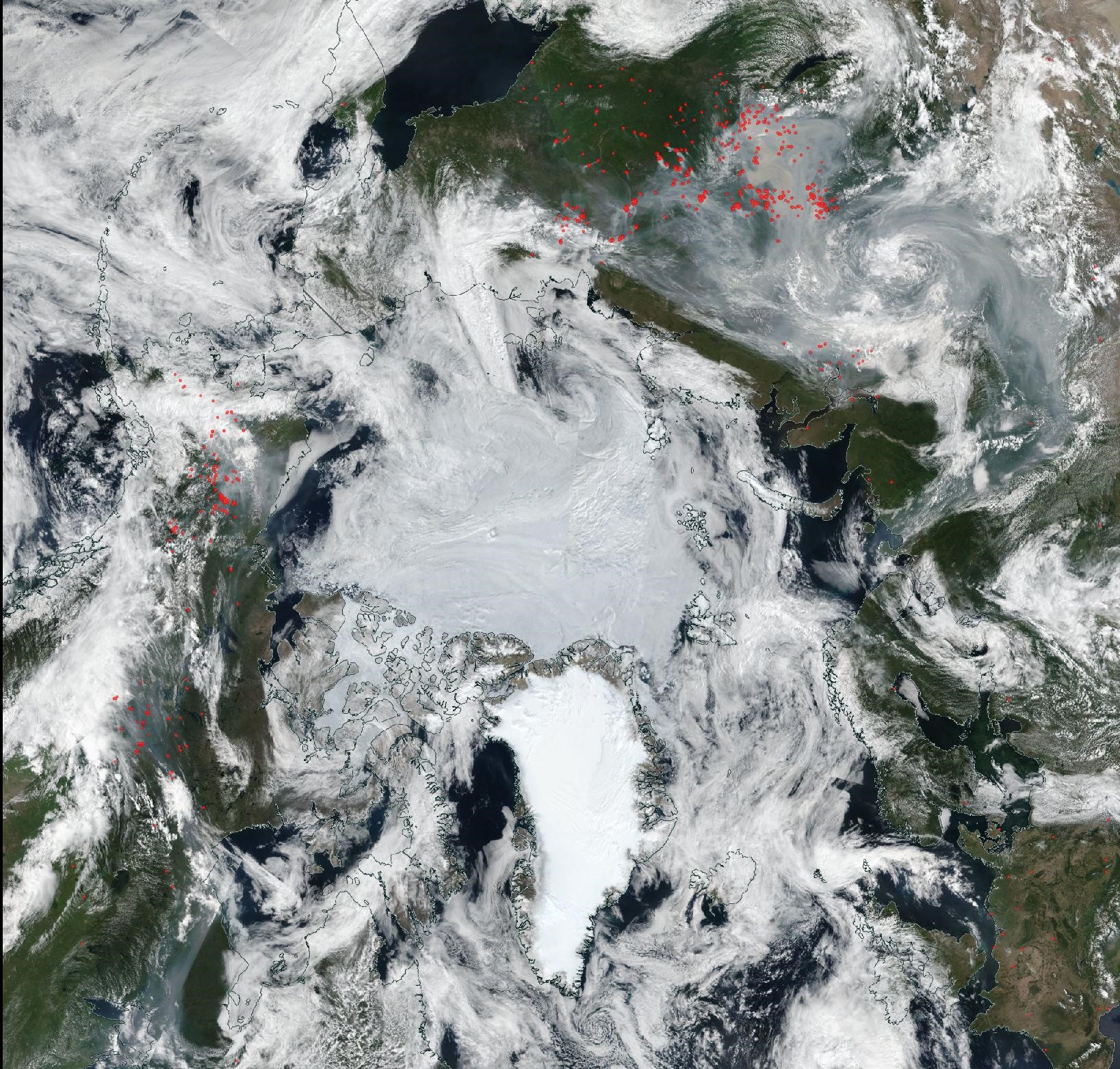

There was an overwhelming driver for the heat in the far north, he said: the “collapse of sea ice and the long open-water season” in both the Beaufort and Chukchi seas. There was no sea ice within 100 miles of shore from early August to early October, and the sea-surface temperatures soared, he said.

The 2019 record was especially notable because there was no strong El Nino system during the year, Thoman said. Alaska’s 2016 warming was boosted by one of the strongest El Ninos on record, but in 2019 there was only a weak El Nino, one that does not have much effect on Alaska weather, he said.

The ultra-strong 2016 El Nino brought atmospheric warmth up from the south, but three years later, in the absence of that phenomenon, the source of the warming was closer at hand, Thoman said.

“The oceans and sea ice played an outsized role, compared to 2016,” he said.

Crossing the thaw threshold for a full calendar year was in some ways symbolic.

While 2019 was the first full year to officially break that barrier, it was not the first 12-month period in Alaska to do so, Thoman noted. In 2016, the previous record-warm Alaska year, the 12-month periods ending in August, September, October and November also had statewide average temperatures above freezing, he said.

Additionally, through 2019 there were several times when the rolling 12-month statewide temperature average broke the freeze barrier, according to NOAA records. For example, the 12 months from September 2018 to August 2019, Alaska’s average statewide temperature was 32.6 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the records.

The NOAA annual report mentioned numerous Alaska weather superlatives that occurred in 2019. The year included the state’s hottest-on-record month — July, with an average temperature of 58.1 degrees Fahrenheit, 0.8 degrees higher than the previous warmest July. And it included several highest-ever recordings for single days, such as the first 90-degree Fahrenheit day in Anchorage, the report said. And the prolonged Alaska wildfire season was among the weather and climate disaster events that, in total, racked up more than $1 billion in costs across the nation in 2019, the report said.

The New Year brought a short-term reversal to Alaska. A severe cold snap plunged temperatures to sub-zero levels in Anchorage and to the minus-40 and even minus-50 range in Interior and Arctic areas.

But the frigid early days of 2020 do not negate the long-term record, Thoman said.

“One week in a 30-year average means almost nothing,” he said.

While bitter cold caused a quick freeze in the Bering Sea, it does not appear to be a durable freeze, Thoman said. The ice in the center of the Bering Sea is only about three weeks old, and it can be easily destroyed if a wind blows in from the south, he said.