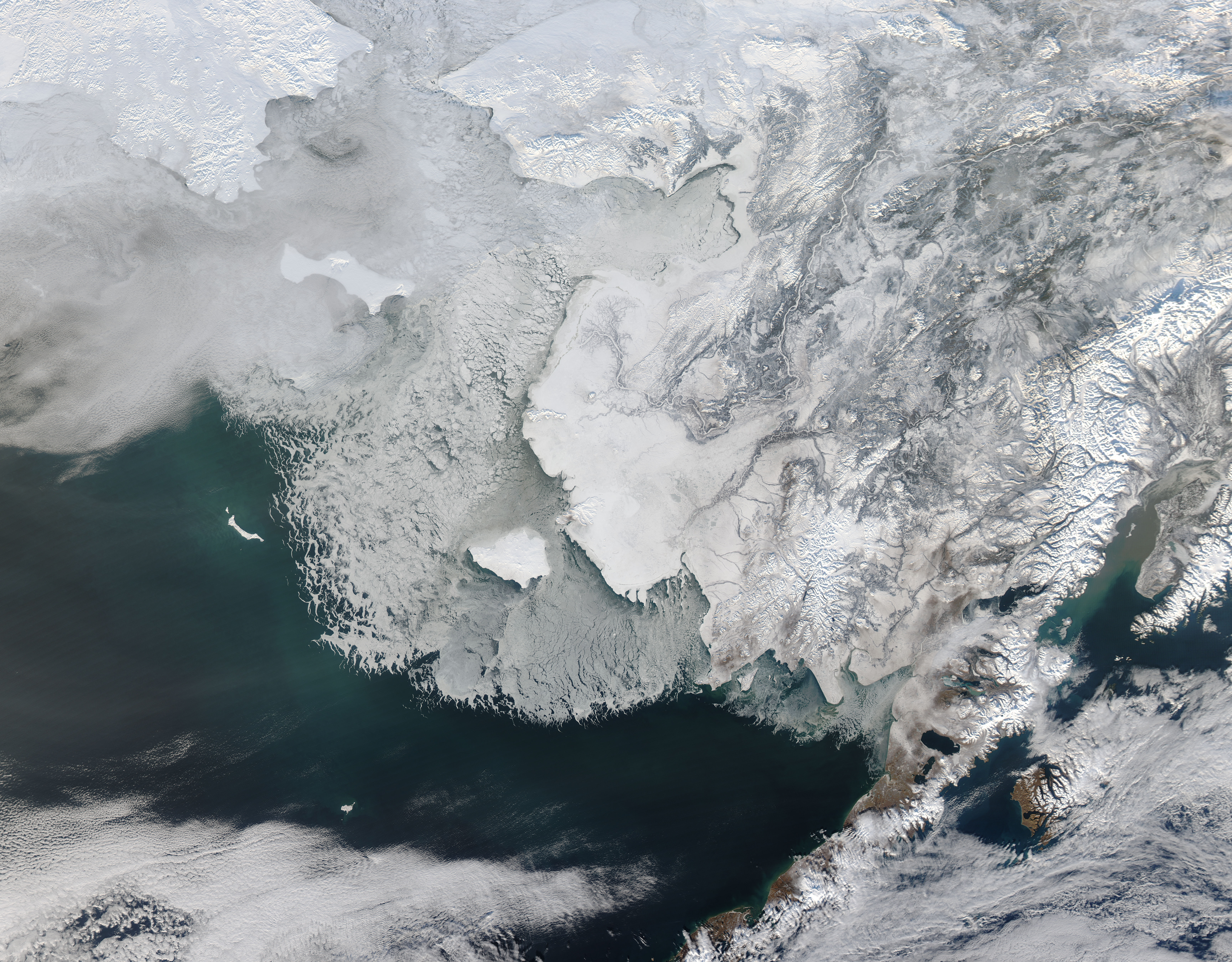

How the loss of Bering Sea ice is triggering cascading effects for the ecosystem — and the people and wildlife that depend on it

The decline of sea ice in the Bering Sea is changing almost everything about the region.

The Bering Sea region, the Pacific gateway to the Arctic Ocean, is home to ecosystems on land and in the ocean that are both abundant and fragile. It’s also changing very quickly — and those changes offer a preview of the changes in store for other parts of the Arctic. This story is part of an ArcticToday series on the changing Bering Sea — and what those transformations mean for fish, wildlife and people.

When a storm lashed the northern Bering Sea in early November, pushing high waves onto the coastal communities there, Paul Hukill fretted about his elderly mother’s cabin on the outskirts of Nome.

His grandparents first settled on the family property there after boating south from Wales, an Inupiat village on the tip of the Seward Peninsula, just 55 miles from the Russian mainland.

In recent years, fall storm after fall storm has sliced away chunks of land from the property and the cabin had already been moved back from the encroaching shoreline in recent years, but the new storm was a fresh assault.

After sunrise followed a turbulent night, Hukill and a friend went to check on the latest damage. They found the cabin swept off the land and set adrift in the Nome River.

This would not have happened if the sea ice were in, Hukill said.

“Right now the ocean should be frozen, you know?” he said in late November, about two weeks after the damage was done. It’s a change he has noticed over the past 10 to 15 years, he said. “When it first started happening, I thought, wait, it’s almost December and there’s almost no ice.”

Hard data backs up those observations.

In the 1980s, the Bering Sea generally started forming significant amounts of ice by early November, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center’s satellite measurements. But since then, the start of the freeze has been delayed, on average, by three weeks, said Rick Thoman of the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“What we know is changing is the early sea ice that used to provide a buffer is gone,” he said.

Spring melt is occurring sooner, too. From 2015 to 2020, the Bering Strait became ice free, on average, 18 days earlier than it did from 2010 to 2014, according to data collected from walrus hunters and presented at this year’s meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Recent years’ ice loss has been stunning.

In 2018, the Bering Sea held the least amount of winter ice in any winter in the past 5,500 years, according to a study that examined isotopes in the peat found on one of the sea’s islands, uninhabited St. Matthew. Winter sea ice used to routinely extend to St. Matthew, about 400 miles south of the Bering Strait, and points beyond, serving as a platform for mammals like arctic foxes and even polar bears; now it rarely reaches that far south at all.

The overwhelming evidence is that human causes are behind the loss of the ice that regulates the Bering Sea ecosystem and protects Bering Sea people and their property, according to research by Thoman and colleagues at UAF.

Even when ice forms, it is present for shorter durations and is thinner, weaker and more ephemeral.

Dog musher Sean Underwood can attest to that. He was closing in on the finish line in his first Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race finish this March when he and two other teams plunged into “this Olympic-sized swimming pool of water,” he said months later. Ocean swells had pushed through the ice — which is normally at its thickest at that time of the year — to inundate a section of trail about 20 miles from Nome finish line. Underwood and two other mushers and their dogs, slogging through water for hours and fighting off hypothermia, were rescued.

All signs suggest the Bering’s ice loss is feeding into a self-perpetuating spiral.

Sparse ice in one year allows to more solar heat to be absorbed by dark ocean surfaces for longer periods of time. That heat makes it harder for ice to form in the next year, leading to more open water areas and a repeat of the cycle — as was seen this year, when Bering Strait ice didn’t even begin to form up until early December.

Since sea ice regulates the whole marine system, its loss reverberates.

That starts with the algae that grows on the underside of the ice, the thick brown layer that creates what is known as “dirty ice.”

The ice layer is “like a greenhouse in the Bering Strait region” producing food critical to the creatures swimming below and flying above the ice, said Gay Sheffield, the Alaska Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program agent in Nome.

“Krill eat the algae, arctic cod eat the krill, birds eat the Arctic cod, we eat the birds, the seals eat the arctic cod,” Sheffield explained in one of the periodic “Strait Science” presentations hosted by the Marine Advisory Program and the UAF Nome campus. “When we have ice we really have rich water. It’s kind of like a giant subsidy for zooplankton and for the whole food chain.”

After the spring melt, the ice algae drops down to the sea floor, where it nourishes clams, worms and the other bottom-dwelling creatures — and the fish, marine mammals and deep-diving birds that eat them.

When ice is gone, ice-associated phytoplankton is, too. What blooms is a different kind of phytoplankton that favors pelagic sea life — fish swimming near the ocean surface and the animals that eat them — over the benthic life concentrated on or near the seafloor. Cold-adapted, high-fat species, such as Arctic cod and some species of krill, suffer from the change while other, lower-fat species move in from warmer waters and benefit.

This shift from an ecosystem that supports cold-adapted, high-fat prey species to one supporting lower-fat prey species is believed to have played a role in the waves of mass bird and seal die-offs in the Bering Sea. It’s also suspected as a cause of a continuing die-off of gray whales that stretches from Baja California to the Chukchi Sea north of the Bering Strait; the northern Bering and the southern Chukchi are where those whales get almost all of their food for the year, and they depend on big loads of krill and tiny crustaceans called amphipods — high-fat marine creatures that get their food from the ice algae.

Winter ice regulates fish populations, too. In normal times, the winter ice that forms in the Bering expels salt as it freezes, and that salt that drifts down super-chills the water below so that it sometimes remains liquid even at below-freezing temperatures. That colder, heavier water, with temperatures at 2 degrees Celsius or below, is known as the “cold pool.” It acts a barrier separating the boreal species such as pollock and Pacific cod, which are big commercial targets in the southern Bering Sea, from the higher-fat Arctic species such as Arctic cod, which are important food sources for marine mammals.

When the cold pool is missing or significantly reduced in size, boreal species move north and Arctic species can be overwhelmed.

Crab fishermen in Nome saw the results in the summer of 2019, when the pots that they use to harvest high-priced Norton Sound king crab were showing up filled with Pacific cod instead. In 2020, there were so many concerns about the health of the crab stocks that the crab harvest was effectively shut down. For Pacific cod, the story is different. Scientists have reported finding juvenile fish Pacific cod in the northern Bering Sea, evidence of not just presence but reproduction in those northern waters previously outside their range.

“There’s a lot changing out there. There’s new species showing up,” said Nome fisherman Jerry Bernhardt, who was in his boat at the local harbor at the start of October sorting bait in preparation for a late-season cod-fishing trip.

Compared to the massive and meaty Norton Sound king crab — which is prized as a delicacy — Pacific cod is a ho-hum commodity. Nome fishermen were paid an average 73 cents a pound for cod this year, according to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game — roughly a tenth of what fishermen fetched per pound in 2019 for king crab. The Pacific cod harvest in those northern waters is just emerging, and what cod lacks in per-pound price it might make up in quantity.

“It’s an opportunity we didn’t use to have,” Bernhardt said. “It’s a volume thing. You have to bring in a lot of them to make it pay.”

It was worthwhile even in October, when most Nome fishermen had docked their boats for the year. “The cod are still out there. They’ll be out there for a while. The water’s still warm,” he said.

What worries local fishermen is the prospect of big industrial-scale cod-harvesting vessels sailing north to harvest the fish, something that has already started. “That would wipe us out,” Bernhardt said.

On the Russian side, fishing vessels have been moving north to chase pollock, an even cheaper fish that’s also moving north as waters warm, as joint U.S.-Russian research shows.

Pollock, a bottom-dwelling whitefish, is used for fish sticks, fish burgers and surimi, the fish paste molded into imitation crab meat and other food products. The harvest is massive; on the U.S. side, the pollock fishery accounts for about a third or more of the total U.S. commercial fish harvest as measured by volume. It is traditionally caught by trawlers in the southern part of the Bering Sea, in both U.S. and Russian waters.

But this year, Russia opened its first commercial pollock fishery in the Chukchi Sea, north of the Arctic Circle, targeting stocks that have pushed north in warmer conditions. It was a startling development, countering international efforts to prevent the expansion of commercial fisheries above the Arctic Circle because of environmental concerns.

With more fishing vessels operating and various Russian military exercises and other activities on the rise, ship traffic has increased dramatically on the Russian side of the Bering Strait. By the summer of 2020, there were effects on the Alaska side. Waves of fresh trash, including solvent-containing cans and plastic bottles with Russian-language labels, washed up on beaches in Nome, on St. Lawrence Island and other Bering Strait-area sites.

Ship traffic on both sides of Bering Strait ship traffic on both sides of the maritime border is expected to keep increasing.

The Bering Strait is the entry or exit point for the two major Arctic shipping routes that are getting increasing use as ice retreats: the Northern Sea Route across the top of Russia, which had record traffic in 2020, and the famed Northwest Passage over the top of Canada, which was once impenetrable. Ship transits through the Bering Strait more than doubled between 2008 and 2015, from 220 to 540 transits, according to the UAF Center for Arctic Policy Studies.

The length of the shipping season is expanding, too. In 2020 thanks to the dramatic melt off Siberia, the Northern Sea Route was clear of ice for longer than any period on record, for example, opening earlier in the spring and staying open through early winter.

The same goes for the U.S. side of the strait. “The shoulder seasons are growing because of their ability to access water earlier and stay later,” said Joy Baker, director of the Port of Nome.

Increased shipping presents economic opportunities in addition to posing environmental risks.

At the Port of Nome, there are plans for a massive expansion that would create the first U.S. Arctic deepwater port. The project would extend the current causeway about 3,500 feet, extending reach into deeper waters of Norton Sound and bending in an L-shape to provide shelter from winds and waves. The sound itself would be dredged to accommodate deep-draft vessels that, for now, must anchor well offshore if they stop at Nome. The project is expected to cost around $500 million for direct construction and another $128 million for onshore improvements. The project won Congressional approval as part of the massive Water Resources Development Act of 2020, passed just before the end of the year, but it also depends on Nome’s ability to raise some money to add to federal funding.

The expanded port could be a boon to other developments. Among them: a project that would develop the nation’s biggest known deposit of large-flake graphite, a strategic mineral used for steel production and lithium batteries. The mine proposed by Graphite One Inc., at a site about 40 miles north of Nome, would ship 60,000 metric tons of graphite concentrate a year through the port, according to preliminary plans.

Tourism, though interrupted in 2020 by the coronavirus pandemic, is also growing in the Bering Strait region as the ice retreats. Cruises between the Alaska and Russian sides of the Bering Strait have become hot tickets for adventure travelers. Nome is a key port of call for cruise ships, including luxury vessels sailing the newly opened Northwest Passage and selling berths for prices that can exceed $40,000. A record 14 cruise-ship stops had been scheduled in Nome in 2020 before the coronavirus pandemic halted travel, but the business expected to resume next year. As of late 2020, 12 cruise ship calls were planned for 2021, with an additional four possible, said Nome Harbormaster Lucas Stotts.

For fishermen, the shift in fish stocks offers some opportunities beyond Pacific cod. Pink salmon, the most plentiful of Alaska’s five salmon species and a staple in the southern part of the state, is starting to flood the northern Bering Sea. Pink salmon are famous for their quick population turnover; their two-year life cycle, much shorter than those of other salmon species, make pink salmon populations more nimble about shifting location in response to changes in environmental conditions. Pink salmon are also notoriously low-priced, fetching an average 35 cents a pound statewide from 2014 to 2019. Can northern Bering Sea fishermen learn to love them? Possibly, if there were a local cannery or some other facility to add value to pink salmon that might otherwise go uncaught, said Bernhardt. “There’s a lot of them. They should be used probably,” he said. “It seems like an underutilized resource around here, anyway.”

In the long term, the people of the Bering Strait region will have to find a way to live with the transformation, scientists say.

Among those issuing warnings is Thoman. The low ice conditions that seemed shocking in 2018 are expected to be typical by the 2040s, he said. By the 2060s, those 2018 conditions are likely to be “a high-end event” for ice, he said.

What’s wrong with this lovely photo of beautiful winter sunshine taken by S. Ozenna Thursday? Looking west from Iŋaliq (Little Diomede) across to Imaqłiq (Big Diomede) in the Bering Strait. What’s wrong: NO SEA ICE. Not a speck. Dec 3rd! #akwx #seace @Climatologist49 @brdemuth pic.twitter.com/rsdXz4bhT7

— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) December 4, 2020

Thoman has his own connection to Bering Sea ice. He started his Alaska career working for the National Weather Service in Nome in the 1980s, and he well knows how the ice used to be. In his Nome days, he said, he would walk with his dogs onto the ice pack, where there were tall rafts of ice reaching well above his head.

Those conditions are history, he said. “We’re not going back to the 90s and before,” he said. “What we have now is, I hate to use it, `the new normal,’” he said.

In the short term, living with less sea ice means coping with more waves and storm-tossed waters.

Subsistence hunters who used to travel over thick, stable ice are directly facing those challenges. “When I was hunting with my grandpa, it was always calm. It would be like glass over the ocean,” said Hukill. “As I got older, I noticed the weather was getting worse, the seas are rougher.”

Hukill is now exploring ways to save his mother’s cabin, which came to rest in a marshy area on the other side of the river. He’s considering moving it, rebuilding it, or both. He is also looking into some kind of land transaction to compensate for the lost piece of family history.

“It’s kind of sad to see it go,” he said. “We used to have all kinds of land.”

This story was supported by a Western Journalism and Media Fellowship from Stanford University’s Bill Lane Center for the American West.