Gjoa Haven elders share Franklin-era oral history with researchers

“It's not part of history, Inuit told the white men only enough to get them to stop asking questions.”

Some of the last survivors of the doomed Franklin expedition may have met their demise at the hands of Inuit who they made the mistake of threatening.

That’s according to one story from Gjoa Haven gathered by researchers who are part of the Franklin Inuit Oral History Project.

The project, led by Parks Canada and the history consultants Know History, visited Gjoa Haven — which is located near the Franklin wrecks — last week to share the traditional knowledge they’ve collected so far from Inuit elders, and to hear more stories.

James Qitsualik, a Gjoa Haven hunter and the project’s oral history field trip expedition leader, told Nunatsiaq News of one story that involves the last few men who survived one of the Franklin wrecks. He said he had heard that there were 80 or 90 men and Inuit tried to help them at first.

When the Inuit left and returned, there were only five to seven survivors.

“Inuit were not afraid of the white men because they were frail,” Qitsualik said.

Some Inuit came across a man gnawing on a cat, Qitsualik said.

Additionally, a group of Inuit women made mitts for the last three surviving men, the kind with no thumbs that are intended for babies, he said.

When they went to bring them into an igloo, some of the men had weapons, and when Inuit feared for their own lives, they killed the men first.

“It’s not part of history. Inuit told the white men only enough to get them to stop asking questions,” Qitsualik said.

Other accounts told to researchers reinforced how the locations of the wrecks were no mystery to some Inuit.

Qitsualik said one man, now deceased, would often recount the time he hooked gum off the deck of the Erebus with a fishing line, and went on to chew it.

“He said it tasted awful,” Qitsualik said.

Stories of elders captured on video

Both these stories were shared on Feb. 27, during a public event at the Nattilik Heritage Centre. It was part of a week-long trip that involved meetings with elders and two community events.

During the events, the group presented the unofficial histories that had been gathered so far throughout the project. They also collected feedback for the book in the works.

“It’s an important phase of the ongoing project to share and gather use of the land traditional history,” said Tamara Tarasoff, the project’s manager.

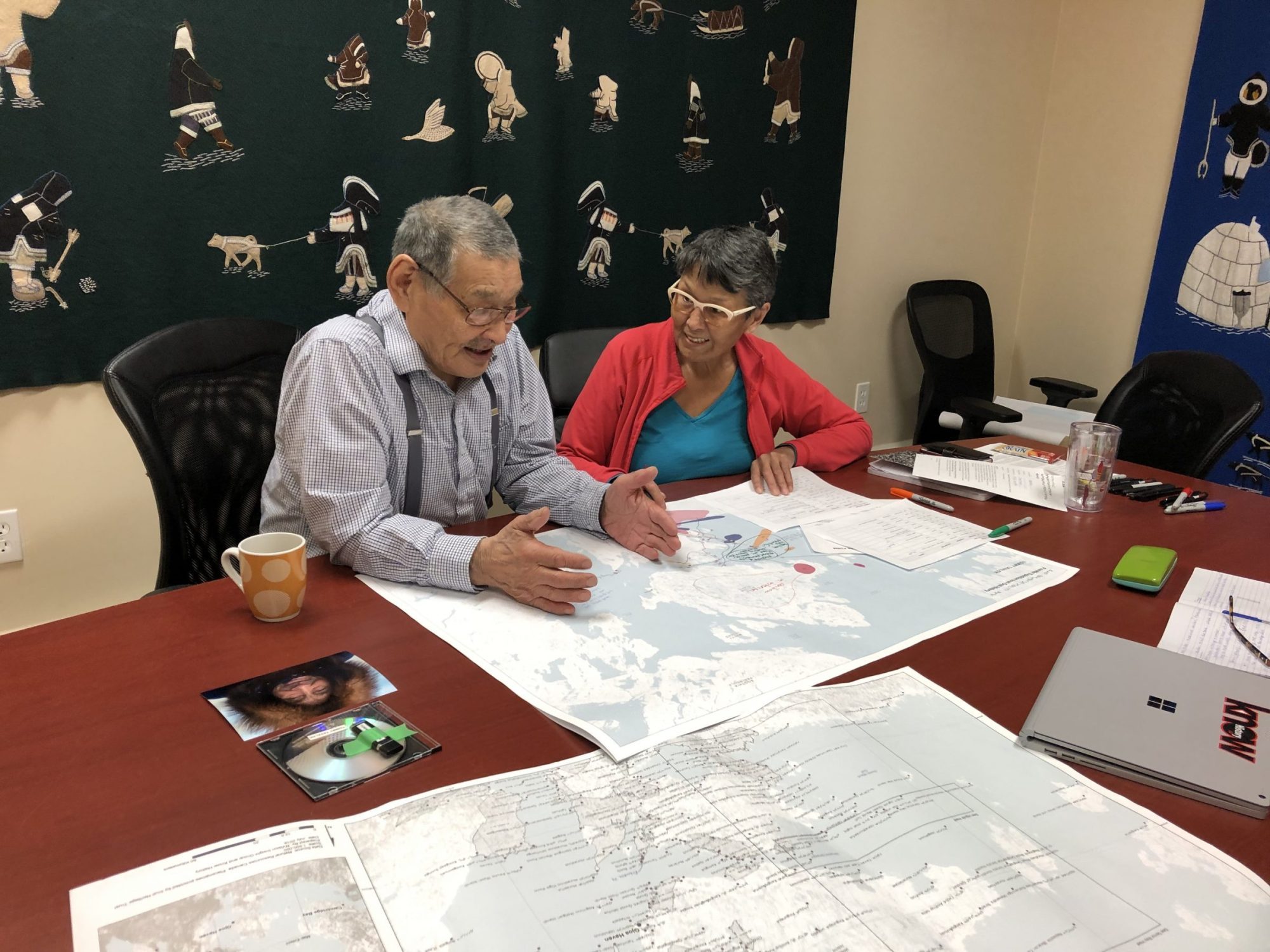

The former Nunavut commissioner, Edna Elias, the project’s lead interviewer, spoke to elders and youth about land and sea use, as well as that of their parents and grandparents. These interviews were filmed.

She also had the responsibility of reviewing maps created for the project and to update them based on information gathered from the interviews.

Last week interviewees got to watch themselves on the screen, and they received copies of the filmed interviews to share with friends and family.

“The elders were just tickled pink to see themselves on the videos,” said Elias.

Forthcoming book will tell Inuit side of Franklin

When the oral history project wraps up in December, the group plans to submit a trilingual manuscript about Franklin expedition oral history, as well as Inuit occupation of the area where the wrecks where found. It will be in English, French and Inuktut.

During last week’s Gjoa Haven visit, the group held a book project workshop with the community to gather feedback on the contents and the potential cover design.

Barbara Okpik, a Gjoa Haven youth and oral history field trip participant, said this project is important for Inuit because it brings together youth and elders.

For Elias, hearing these firsthand accounts of stories has been a unique experience.

“I got to hear place names from these people, now that the story is out,” said Elias.

“When these elders were children it was hush hush… They knew of the ships, but they didn’t want the influx of qallunaat up here.”

Traditionally, Inuit children were not supposed to talk about the stories of the first contact, Qitsualik said.

The whole area has been used a long time for Inuit, said Qitsualik, who led expeditions to the islands near where the wrecks had been found.

Qitsualik said one tiny island to the west of Terror Bay is dotted with seal caches, which he said clearly goes back hundreds or thousands of years. He led expeditions to the islands and area near where the Erebus and Terror wrecks were found.

“It just goes to show that this land was used by Inuit for a very long time,” Qitsualik said.