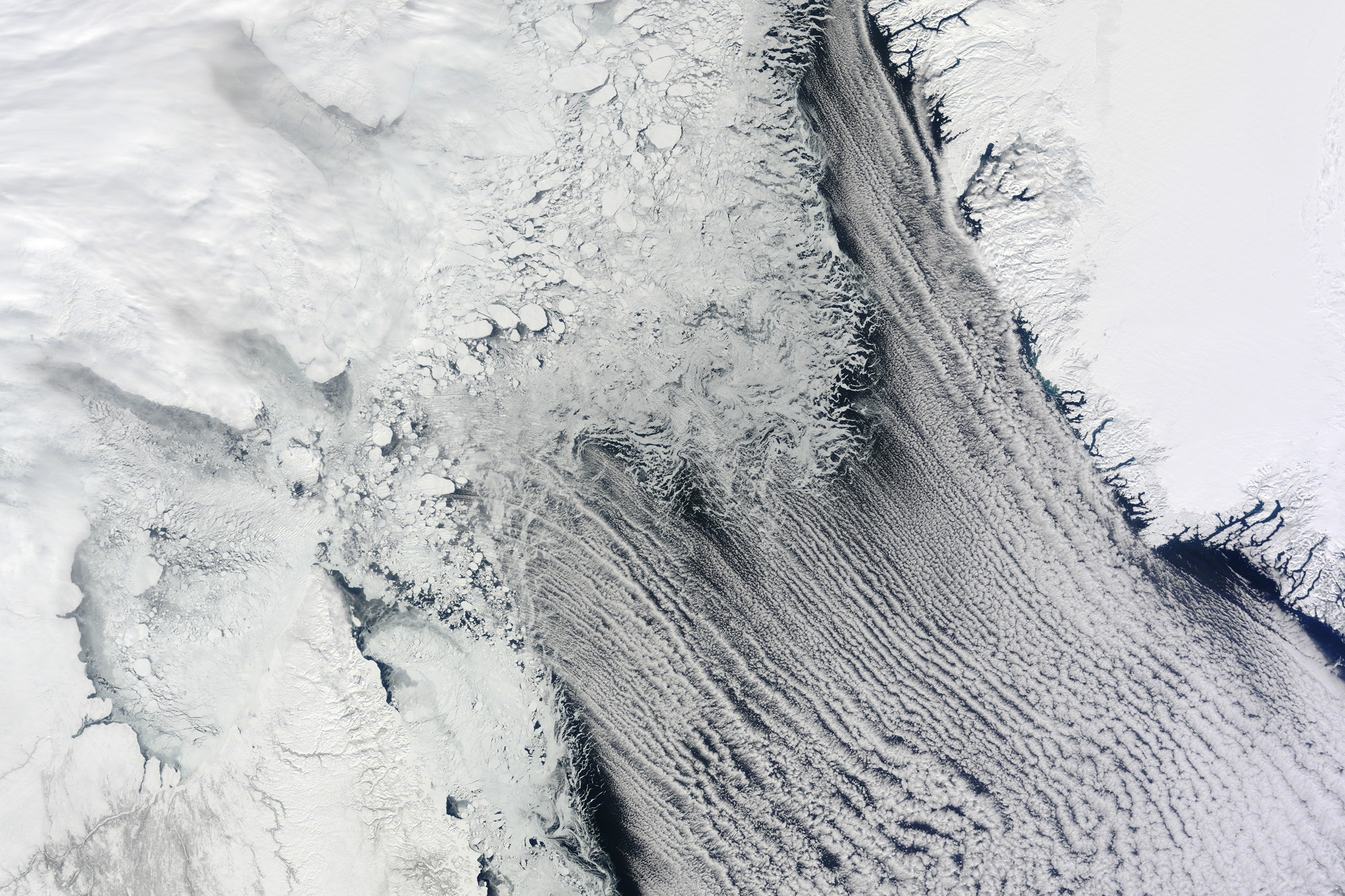

Changes in cloud cover might be slowing Arctic warming. For now.

In recent years, the news about sea-ice in the Arctic has been consistently bad: All 10 of the lowest summer minimum extents on record have been measured in the past 10 years. Now, new research suggests that the situation could have been worse were it not for a naturally occurring cooling effect that is set up, ironically, by the introduction of heat and moisture into the air over the Arctic Ocean.

Scientists have long focused on the warming effect of increasing cloud cover over the Arctic Ocean. This is because as heat and moisture move into the region, more low-level clouds are created and, since water vapor retains heat, the energy is trapped and returned to the surface, causing air temperatures to rise.

The paper, to be published in a forthcoming edition of Geophysical Research Letters, finds that while the heat and moisture transport into the Arctic during the summer leads to more heat-trapping clouds, it also sets up a “robust” cooling effect that equals — or in some cases is greater than — the amount of energy trapped by the lower-level clouds.

This is because as more low-level clouds are created, fewer high-level clouds form, allowing more energy to be released into space. The absence of high-level clouds is akin to an open window. The fewer clouds there are, the wider the window is open.

While not enough to counteract other factors that lead to warming temperatures, the effect leads to what the paper’s authors describe as a “buffer that prevents runaway Arctic warming.”

One factor that plays a role in how much energy is released into space is the extent of sea ice.

Joseph Sedlar, an atmospheric scientist with SMHI, the Swedish met office, and the paper’s lead author, explains that since sea ice cannot rise above the freezing point while it still remains ice, any additional energy in the atmosphere over ice-covered areas must be transported into the atmosphere, contributing to the cooling effect.

Further research is required to determine what impact increasing stretches of open ocean would have, but Sedlar reckons it could reduce the role the buffering effect plays. In the event sea ice disappears entirely, he suggests an opposite effect may arise as the ocean retains increasing amounts of energy.

The forecast: warmer, with a chance of amplifying.