Climate change has barnacle geese racing north

As Arctic change accelerates, will birds be able to keep up?

Hundreds of thousands of barnacle geese flap their way to the Arctic each spring to breed and raise their chicks on the greening tundra. They time their arrival with the spring snowmelt, so that when the chicks hatch, they can dine on lush sedges and other plants.

But as Arctic temperatures have warmed, these geese have sped up their 3,000-kilometer (roughly 1,800-mile) migration to reach their destination more quickly, according to new research.

In years with earlier snowmelt, they arrived at the breeding sites up to 13 days sooner. The trouble is, when they get there, they’re not laying their eggs in time for their goslings to capture the food peak.

“They migrated nearly non-stop to the breeding areas,” says Bart Nolet, an ecologist at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology and the University of Amsterdam, and one of the study’s authors. “We didn’t think they were capable of doing that.”

Now, scientists are worried that Arctic temperatures may be warming too fast for the barnacle goose. They’re wondering whether the birds will be able to keep up.

Hungry birds

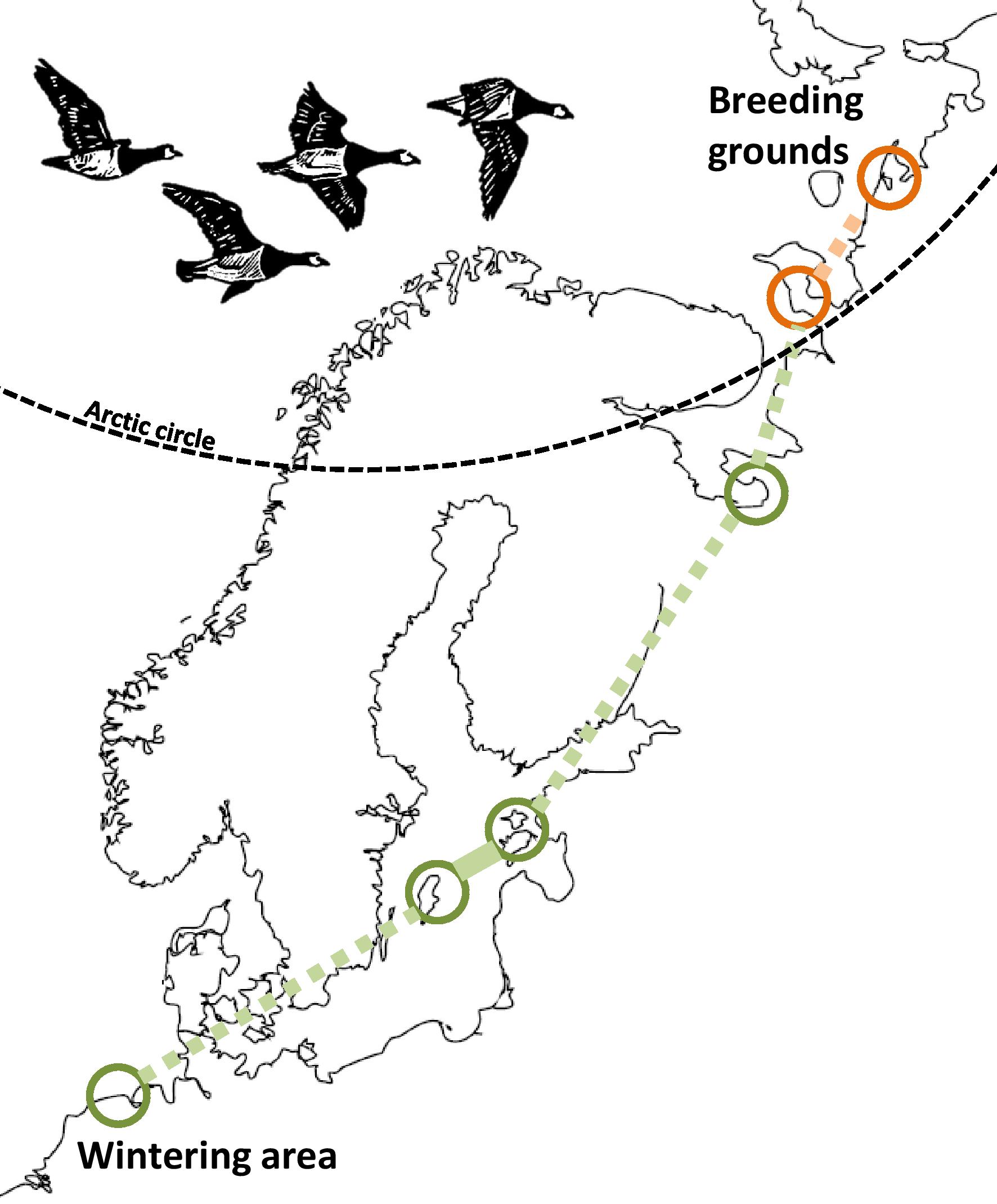

For the study, published on July 19 in Current Biology, the researchers outfitted the geese tracking devices to monitor their migration from their temperate wintering grounds in the Netherlands to their Arctic breeding grounds in the Russian Arctic.

In a typical spring, the barnacle geese make several stops along the route, in the Baltic Sea and Barents Sea, to refuel. They arrive in the Arctic just after the snow melts and lay their eggs, so that the chicks hatch when the food quality is at its peak.

But during warmer springs, the geese skip their stopovers to speed up their Arctic arrival. It’s a bit like taking an express train that lacks a dining car. Although they touch down earlier, they stop to eat before laying their eggs. The delay creates a mismatch between the spring green-up and the goslings’ hatch date.

Goslings need short, nitrogen-rich plants to grow quickly. But Arctic plants grow faster and larger in response to warmer temperatures, lowering the concentration of nitrogen within their leaves. Goslings born in years with warmer springs and a larger mismatch were less likely to survive, the researchers found.

“It’s not really well timed for the chicks,” says Jennifer Provencher, a marine ecologist who studies coastal birds at Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. “They come to the buffet late.”

Other goose species

While some Arctic birds are suffering from sharp drops in their populations, barnacle geese are experiencing a boom, at least for now.

Once hunted for meat and eggs, the species is now fully protected throughout its range, which stretches from the northern coasts of the United Kingdom and Europe to Greenland, Svalbard and parts of Russia. Estimates suggest there are 880,000 barnacle geese globally.

The warming climate is also opening up new territory for barnacle geese. In the 1980s, researchers thought Spitsbergen, Svalbard could hold 17,000 barnacle geese, but there are 42,000 nesting there now, says Maarten Loonen, an Arctic ecologist at the Arctic Centre at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, who studies barnacle geese in Svalbard.

“The seasons were considered too short, but now they are one month to one-and-a-half months longer,” says Loonen.

Scientists have fewer details about the migrations of less-abundant Arctic-nesting geese, such as the lesser white-fronted goose. While they may also be able to speed up their migrations, it may come at too great of a cost, if the goslings don’t survive.

Early bird

The researchers say barnacle geese can only fully adapt to a rapidly warming Arctic if they leave their wintering grounds earlier. The migration, and its route is a learned behavior, that parent geese pass onto their offspring, meaning they might be able to adjust.

“If they do do something else, that new behavior can spread very rapidly,” says Nolet. “That may be the rescue for these birds.”

Still, Nolet says, it’s too early to know the long-term implications. Winter survival of barnacle geese has “increased enormously” because of their access to higher quality food in agricultural areas, he says. “This is more about the fast changes occurring in the Arctic and that these birds are having trouble keeping up.”