Bomb threat, COVID throw Greenland’s Kuannersuit mine approval process into disarray

Authorities say public hearings will go ahead despite bomb threats. But local political opposition to holding meetings during the pandemic may halt the process anyway.

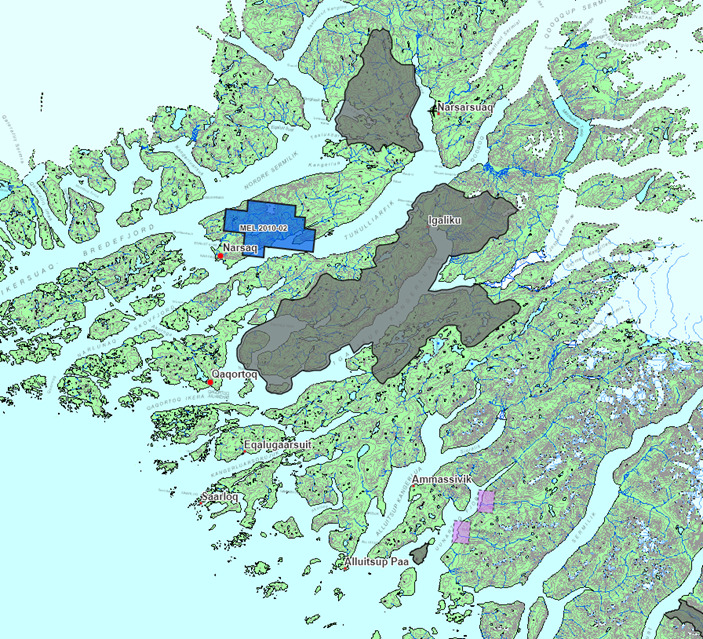

A series of public hearings due to begin Friday about a potential rare-earth and uranium mine in southern Greenland will go on as scheduled, despite that country’s mining ministry receiving what it said were death threats against the members of the cabinet planning on attending, according to that country’s mining ministry. But growing local concern that limits on the number of people attending meetings due to measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 now has some influential lawmakers suggesting that changes be made to the meeting session.

In a statement on Friday, Jens-Frederik Nielsen, the mining minister, announced that Naalakkersuisut, the elected government, had received a bomb threat and a warning that “weapons would be used” if the meetings went ahead.

Despite downplaying the threats as “possibly not specific,” the mining ministry said it was taking them seriously, and that the three members of the cabinet due to take part in the meetings would therefore not participate in the meetings “initially.”

Citing what he called “misinformation” surrounding Kuannnersuit (also known as Kvanfjeld), and an “agitated” public sentiment, Frederiksen said he needed to take the threat seriously.

“I need to accept that reality and take temporary steps, such as not taking part in the public hearings in southern Greenland,” he said.

For now, the series is slated to otherwise go on as planned. The sessions had been billed as an opportunity for members of the cabinet to address residents and hear their concerns, but more important, though, according to Nielsen, is that concerned citizens get the chance to confront Greenland Energy, the Australia-listed firm whose application to operate a mine at Kuannersuit comes a decade after it received permission to explore there. The firm will still show up, as will public officials involved in the approval process.

However, local lawmakers say Naalakkersuisut cannot hold its meetings and not be there, too; the regulations for the approval process, they point out, explicitly state that if a representative from the cabinet is not present at a meeting, public hearing period must be extended. Whether this applies in this case is up to debate, however; the public comment period was already scheduled to last 12 weeks, rather than the mandatory eight.

Those lawmakers had already been calling on Naalakkersuisut to either add more meetings to the schedule or to delay them entirely until COVID-19 restrictions — which cap indoor gatherings at 100 participants — could be lifted, to make sure that as many people as possible could attend.

[A pair of US-Greenland education partnerships get State Department funding]

A similar cap on outdoor gatherings, this one of 250 people, has been cited by opposition groups as a preventing them from showing the true depths of public sentiment against the mine.

In a letter sent to Naalakkersuisut last week, the heads of all of the parties represented on the Kujalleq regional assembly called for more meetings to be added. They would also like KNR, a publicly funded broadcaster, to devote more coverage to the potential impact of the mine. Lawmakers have criticized KNR’s coverage of Kuannersuit as lacking, particularly after Greenland Energy paid to have an insert singing its praises published in SermitsiaqAG, the country’s merged newspapers, and to have it delivered to all residents of Greenland by post.

Advocates of a more active KNR point to its role, in 2010, in providing a counterbalance to the public relations campaign, organized by Greenland Development, a nationally controlled firm set up to attract foreign investment, to sell the public on a huge hydroelectric dam. That project was eventually rejected.

The local protests are not falling on deaf ears. Lawmakers at the national level are as divided about the prospect of uranium mining as the population itself. Officially, Siumut, the national assembly’s biggest party, has been a staunch backer of Kuannersuit all along (indeed, the party, in 2013, was instrumental in securing a change in legislation that made uranium mining in Greenland possible), but, now that a final decision is drawing near, some of its heaviest hitters suggest proceeding with caution.

“People are protesting. If the entire assembly is asking for the meetings to be postponed, we can’t ignore them. As a result, we’ve asked for the public hearings to be postponed; we need to learn more before a decision can be taken,” Erik Jensen, who was voted in as party’s chair in November, told Sermitsiaq.

Kim Kielsen, the current premier, and the leader of Siumut until he was replaced by Jensen, has said that the hesitation goes against party’s long-held line. But Vivian Motzfeldt, a party grandee who is from southern Greenland, says the go-slow tack recognizes that the country will not get a do-over on Kuannersuit, no matter what it chooses. With the issue evoking violent reactions amongst the people of Narsaq, where the mine is to be located, a pause for reflection is warranted, she reckons.

“With such a big issue facing us, and with the level of opposition, and when opinions are as deeply divided as they are now, we ought to find a new approach. The most valuable thing we have that can protect us as a small population is our sense of community,” Motzfeldt wrote in an op-ed in Sermitsiaq.