As NASA resumes polar ice monitoring by satellite, some Arctic data may be passed over

NASA's Operation IceBridge is ending as ICESat-2 takes over polar ice monitoring. But the satellite is unable to collect some of the same data, scientists say.

Last week, NASA’s Operation IceBridge began its final campaign to measure polar ice and snow cover.

This IceBridge mission will conduct 15 to 25 flyovers in Antarctica, using lasers mounted to a plane to determine ice thickness on land and sea, as well as snow cover and other conditions.

After that, ICESat-2, NASA’s new ice-measuring satellite, will take on polar data-collection missions.

ICESat-2 launched in September 2018, but IceBridge continued collecting data for a year in order to calibrate the results gathered by satellite.

“We are basically passing the torch on to ICESat-2 to continue the fieldwork,” John Sonntag, a scientist working on Operation IceBridge, told ArcticToday. “That’s the end of IceBridge.”

IceBridge conducted two short missions in Greenland this year. The first, in the spring, was truncated by the government shutdown, which affected the quality of data collected.

“We got a credible campaign, but not the one we would have hoped for,” Sonntag said. They also encountered bad weather and maintenance issues — which complicated the already-shortened timeline.

Sonntag called the temperatures on the ground during the spring campaign “astonishingly warm.”

“There were days it was in the low sixties, in April in Greenland,” he said. “We were walking around in short sleeves. So that was pretty remarkable.”

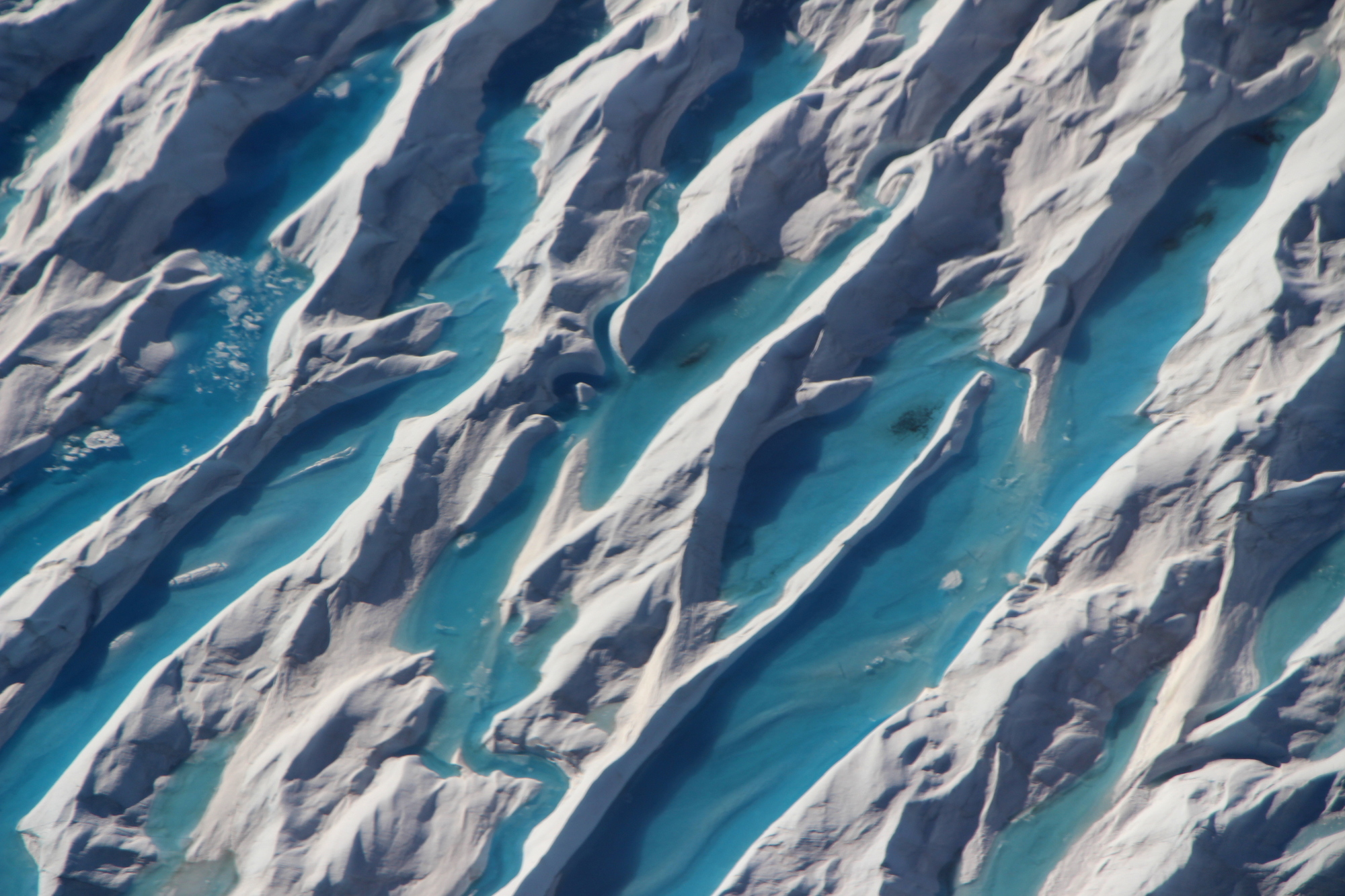

The second Arctic campaign, in early September, attempted to quantify Greenland’s melt after record-high temperatures and an early onset of melt. The data is still being processed by the team.

The IceBridge team will continue to process data and conduct other closeout work for the next six to 12 months, but this is the final mission involving field work.

After ICESat ended in 2009, Operation IceBridge was launched to provide regular measurements before ICESat-2 would be launched a decade later. It was always intended to be a bridge, Sonntag said — but it evolved into something more.

The primary mission remained the same as ICESat and ICESat-2: to measure how the volume of the ice sheet is changing.

“But IceBridge could do things that cannot be done with satellite,” Sonntag explained. The sensors mounted to the low-flying plane can measure how much snow has accumulated, making maps of how much it snows over different parts of the ice sheet. And it also measures the conditions driving the behavior of the ice sheet, such as the shape and wetness of the bedrock and the depth of the ice covering it.

“You can’t do that kind of thing with the satellites,” Sonntag said. “So we’re certainly losing some capability with the closing out of IceBridge. That’s one of the reasons we’re continuing to look for new sources of funding to go pursue some of those questions.”

Ben Smith, a researcher at the University of Washington’s Polar Science Center, told ArcticToday that these factors play important roles in how much — and how quickly — ice leaves an ice sheet.

“If you know how thick the ice is, you can figure out how much ice is bleeding through the glacier,” he said. “And that will tell you a lot about why the ice might be losing mass at a particular spot or for a particular glacier.” This kind of information, he added, would be very helpful in understanding ICESat-2’s data in the future.

Scientists who have worked with IceBridge data praise in particular its ability to focus on specific research priorities — like returning to Greenland to measure the extent of its melt.

“One of the great things about IceBridge is that when we started to see something interesting happening, we could go and check it out,” Smith said.

“My hope is that as we see exciting things happening in the ICESat[-2] data, if we need to know more about them, we’ll be able to do maybe a smaller but more targeted campaign with some of the IceBridge instruments to learn what’s going on there,” he said.

Beata Csatho, professor in geological sciences and chair of the geology department at the University of Buffalo, agrees. “It remains to be seen what we will see from ICESat-2,” she told ArcticToday. “My concern is more that, if ICESat-2 finds out something new and exciting, then we don’t have that easy way to say, okay, IceBridge will go and check it out, for the other measurements.”

However, both Smith and Csatho are very excited about accessing ICESat-2 data. The IceBridge campaigns were limited to places where a plane could take off and fly over in a day, Csatho explained. “ICESat-2 will be wonderful because it really gets continuous coverage everywhere.”

Sonntag said there will probably be projects to continue calibrating and validating ICESat-2’s data. And, he said, they hope to create an ongoing, albeit smaller, series of campaigns to continue collecting the data that ICESat-2 passes over.

“I don’t think any of us have any expectations that we’re going to find anything as big as IceBridge in terms of the amount of field work and the amount of funding,” Sonntag said. “But we’re hoping to be able to sort of fill in some of the gaps that are left after the end of IceBridge and during ICESat-2.”