As the Arctic warms, reindeer herders face encroachment from new industries

The Arctic's rapidly changing climate is opening the door for new industries to operate in the region — and threatening traditional ways of life.

FINNMARK PLATEAU, Norway/OSLO — When he’s not out on the Arctic tundra with his 2,000 reindeer, his dog and Whitney Houston blasting through his headphones, Nils Mathis Sara is often busy explaining to people how a planned copper mine threatens his livelihood.

Along with other Sami herders and fishermen, the 60-year-old is in a standoff with the mine owners, Norwegian officials and many townspeople that is, after six years, coming to a head.

It is a litmus test for the Arctic, where climate change and technology are enabling mineral and energy extraction, shipping and tourism while threatening traditional ways of life and creating tensions among its four million inhabitants.

“This mine is completely nuts,” said Sara, preparing to move his herd from winter pastures on Norway’s windswept Finnmark plateau three days north to the grass-rich pastures on the coast, where females calve and there are fewer mosquitoes.

“We would be losing summer pastures for our reindeer again.”

Herders around the Arctic – in other Nordic nations, Russia, Canada and Alaska – echoed his concerns in interviews, citing threats from climate change, mining, oil spills and poaching as well as thoughtless behavior from townspeople and tourists.

Global majors, including Eni, Equinor, Gazprom, Glencore, Lukoil and Rio Tinto, are all grappling with how to square their prospecting plans with the interests of people whose views count more than in the past.

Anders Oskal, Executive Director of the International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry, said the copper mine was in the spotlight. “Big industry is sitting on the fence and seeing how it plays out,” he said.

Legal action

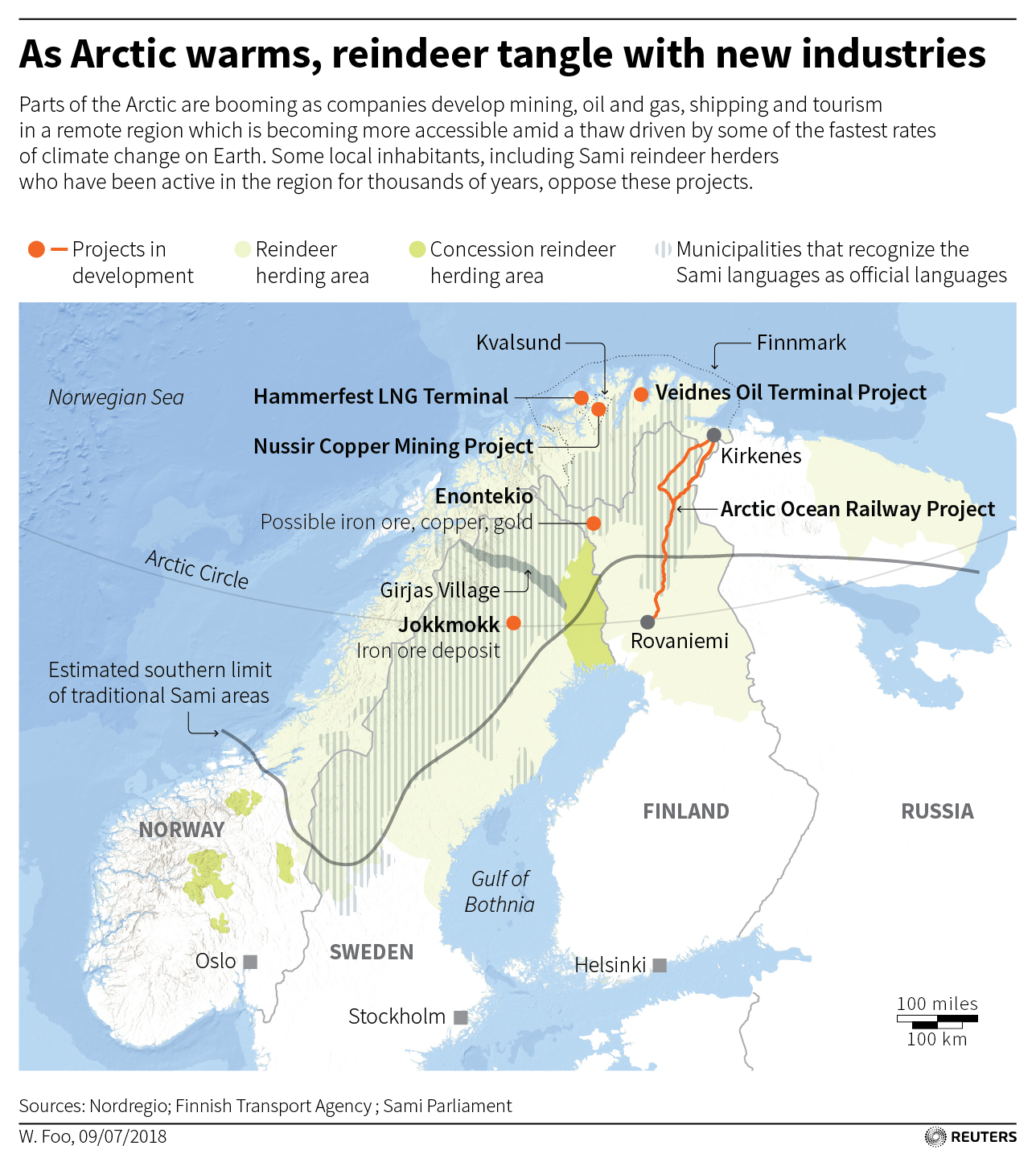

Local officials gave the green light for the privately-owned Nussir copper project back in 2012 on the grounds it would bring in much-needed jobs and funds. It has been stuck ever since.

Indigenous Sami herders and fishermen say the plan to dump the mine’s tailings in the fjord, while less damaging than piling them on land, would destroy spawning grounds for cod and the mine would damage summer pasture grounds and frighten the reindeer.

“I don’t get it,” Tommy Pettersen, a 47-year-old Sami fisherman, said on board his boat, which gives him a potentially lucrative but unpredictable income. “We are a maritime nation. We have relied on the ocean to live off and we want to dump this stuff in the fjord?”

He had just caught king crabs worth 16,000 Norwegian crowns ($1,990). Last year he earned 1.6 million crowns ($199,000) for four weeks’ work — about half from cod and the rest from crabs, a Pacific species brought to the Barents Sea in the Stalin era.

Sara’s income is steadier. He gets up to 130 Norwegian crowns ($16) a kilo for his meat, 300 crowns for each skin and 140 crowns a kilo for the antlers, which he sells to China as aphrodisiac.

Nussir has won the necessary permits, says the area contains 72 million tonnes of copper — Norway’s largest reserve — and plans more than 1 billion crowns ($124 million) in investment.

“We can run this mine alongside reindeer herding and fishing,” said Oeystein Rushfeldt, the head of the project.

Terje Wickstroem, mayor of Kvalsund, a village of painted wooden houses on the Repparfjord with 1,027 inhabitants, said the mine would boost a municipality which spends 40 percent of its income caring for the elderly as young people move away.

“It would create optimism for the town,” said Wickstroem, who is himself a Sami.

After years of back and forth with locals and the consultative Sami Parliament of Norway, as well as assessments by ministries and government agencies, the center-right, pro-business government will make a ruling on the copper mine this year.

Oskal, of the reindeer husbandry center, said it was ironic that Nussir may be allowed to dump waste when Norwegian laws oblige Sami reindeer herders to send the animals’ stomachs and intestines for destruction, sometimes hundreds of kilometers away, to reduce risks of disease.

Traditionally, herders just buried the remains.

The Sami herders insist they are not opposed to change — their language has no word for “stability” — but Sara said the politicians were not listening. “If this mine gets the go ahead, we will go to the courts to stop it,” he said.

Wickstroem said he understood Sara’s concerns. “His business is under pressure. But this is a bigger, national debate.”

It is also an international one.

Shrinking ice

Average temperatures in the Arctic region have risen more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6°F) since pre-industrial times, twice as fast as the world average, according to research for the intergovernmental Arctic Council.

Temperatures now sometimes spike above freezing in mid-winter, melting snow that then re-freezes into a blanket of ice on lichen pastures that the reindeer cannot nuzzle through. In the worst recorded ‘rain on snow’ event, in the Yamal Peninsula in Russia in 2013-14, about 61,000 of 275,000 reindeer died.

“Indigenous peoples and systems in the Arctic” top a list of populations vulnerable to warming in a draft U.N. scientific report about the risks of climate change to be published in October.

Shrinking ice also means liquefied natural gas tankers can now travel west to Europe year-round and east to Asia in summer from the Yamal Peninsula in northern Russia, where Gazprom is the dominant producer.

“There is an explosion of industrial development in Arctic regions,” said Mikhail Pogodaev, Chair of the Association of World Reindeer Herders, who is based in Yakutsk, eastern Russia.

The Nenets herders on the Yamal Peninsula still live in tents and travel with their herds, unlike the Sami, who now venture out on snowmobiles or quad bikes from village homes and overnight in caravans or wooden huts on skis.

Russia does not have Norway’s consultative system — its regional governors are often swapped by the Kremlin — making things easier for companies able to navigate Kremlin politics but leaving the Nenets little power, wealth or legal redress.

Gazprom says it goes out of its way to cooperate with herders, raising pipelines to let reindeer pass underneath and making road crossings where herders request them.

“Around 10,000 reindeer cross via these crossing points during a season,” it said by email.

Oskal, Pogodaev and some academics say Gazprom does plan carefully, but, like all energy majors, it is in the environmental firing line over its impact on global warming, which is speeding up as the polar ice caps melt.

Eat more reindeer

In Norway, some reindeer herders and fishermen noted efforts by Italian oil group ENI to cooperate, for instance using Sami interpreters and discussing the siting of an electric cable that takes power to the Goliat oilfield offshore.

Norwegian Equinor, formerly Statoil, operates the offshore gas field, Snoehvit, in Norway’s Barents Sea, sending gas to a liquefied natural gas plant near the northern town of Hammerfest.

The government is offering exploration licenses ever further north, in areas covered by winter sea ice until recent decades.

Some reindeer herders see the influx of workers as a potential new market for their meat, but say companies rarely buy enough.

A 2007 U.N. declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples obliges states to “obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands”.

In practice, that usually stops short of a veto and lawsuits abound.

In neighboring Sweden, the government has appealed to the Supreme Court to resolve a dispute over management of hunting and fishing rights in the Sami village of Girjas.

And there is a long-running conflict over the Kallak magnetite iron ore deposit near Jokkmokk in Norrbotten county, where British miner Beowulf Mining is pursuing an exploitation concession for the Kallak North project. The Swedish government has not yet taken a final decision.

In Finland, opposition from Sami people and environmentalists has blocked proposed geological surveys for iron ore, copper and gold in the Sami region of Enontekio.

Poachers in Canada

It is not only herders and companies that are facing off. Conflicts of interest between those continuing millennia-old traditions and other residents and visitors are increasing.

Across the Arctic from Norway, in Canada, Lloyd Binder said his 4,000-strong reindeer herd at Inuvik, the country’s biggest, had suffered poaching since a new highway opened to cars in November.

Bruce Davis, of the Midnite Sun Reindeer Ranch in Alaska, says he has just 40 reindeer left from a herd of 8,000 in his father’s day. It was partly because many had mixed with wild caribou, but damage by past gold prospectors and climate change had also taken their toll on the reindeer’s pastures.

Still, some reindeer find ways around their problems. In Norway’s Hammerfest, a 19-km (12-mile) long wooden fence, built a decade ago with money from Equinor, has a gaping hole.

“The reindeer are annoying … They eat all the flowers I plant,” said Karin Karlsen, 78, knitting on her patio while reindeer nibbled at the grass behind her red wooden house.

Additional reporting by Jussi Rosendahl in Helsinki, Oksana Kobzeva and Olesya Astakhova in Moscow, Johannes Hellstrom, Anna Ringstrom and Niklas Pollard in Stockholm.