Arctic sea ice is close to its annual minimum extent — but that’s just part of the picture

The exact annual minimum isn't necessarily the most important thing to look at, scientists say.

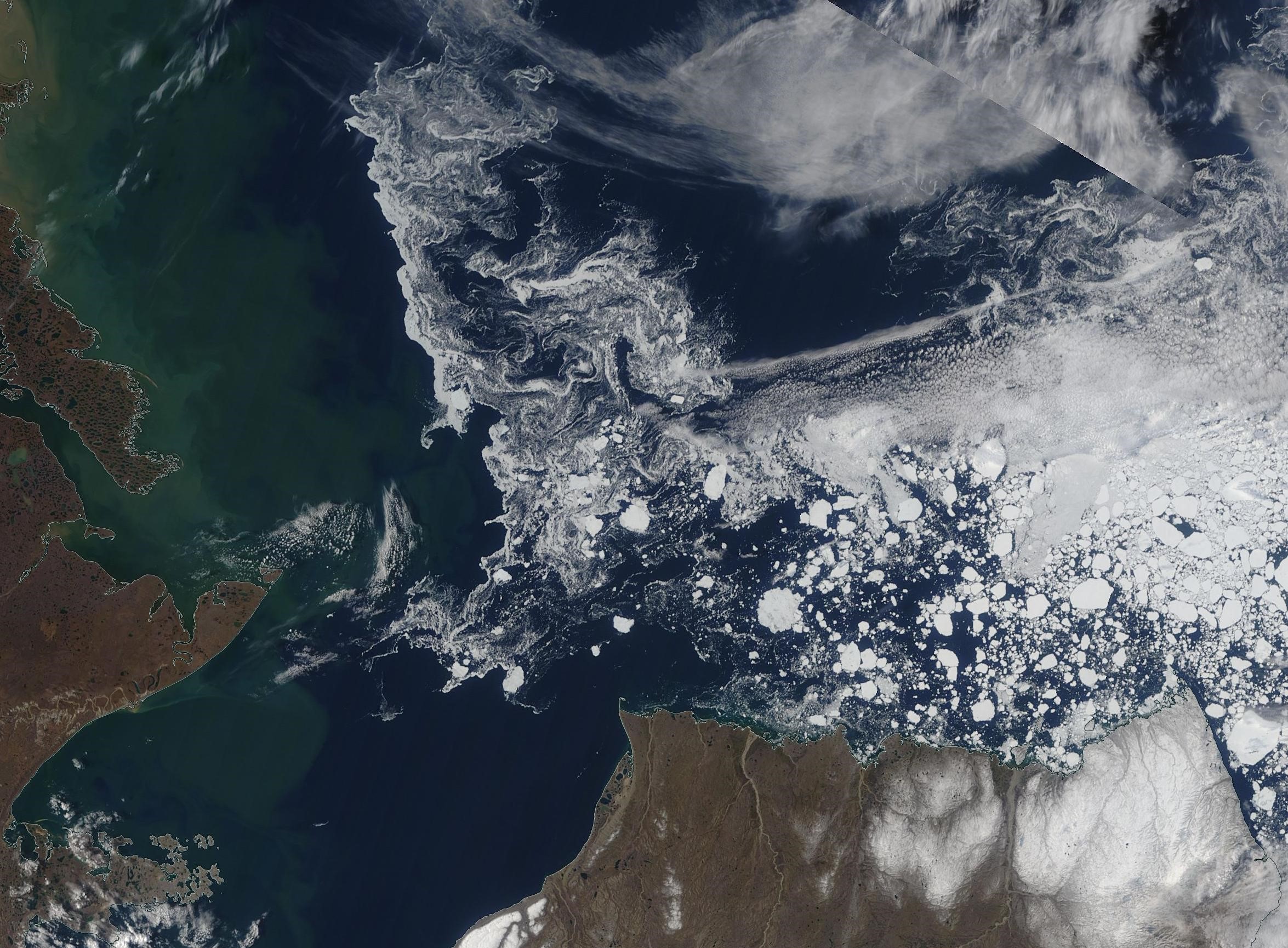

As the autumn equinox looms and winter darkness approaches, Arctic sea ice has dwindled to what appears to be one of the lowest minimums in the satellite record.

“We are basically right now in a dead tie for second place,” Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, said on Wednesday.

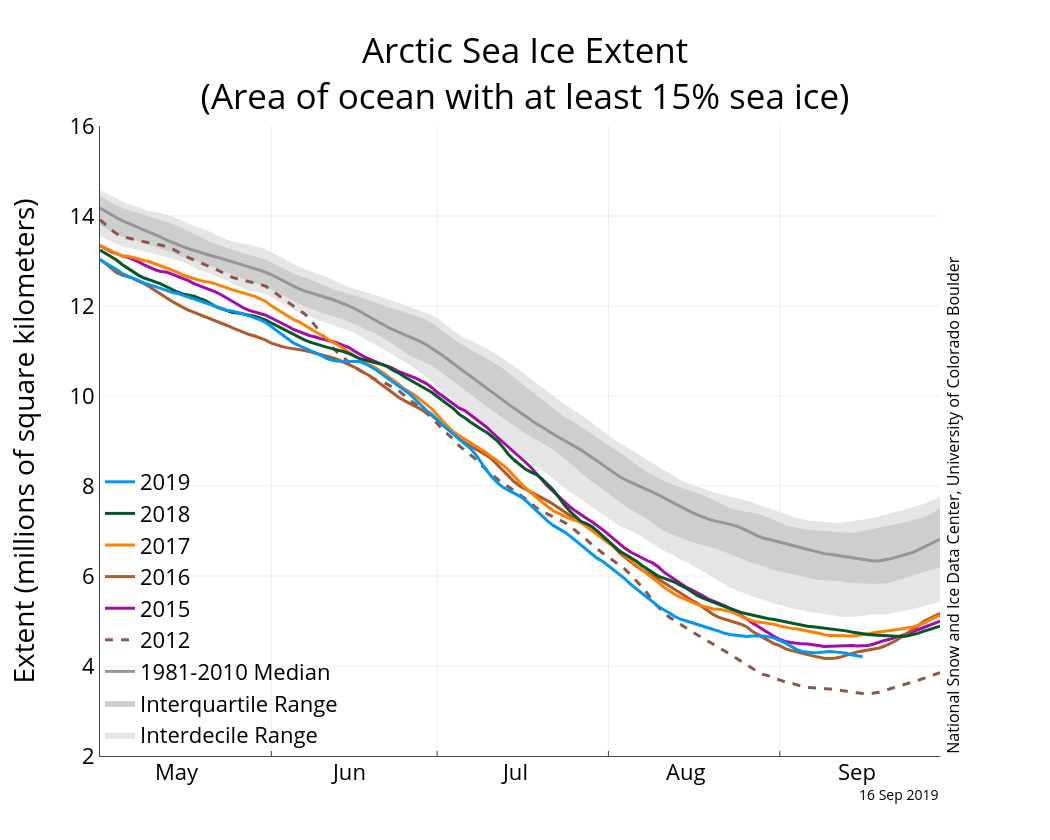

Ice extent — defined as the area where there is at least 15 percent ice coverage — dropped to 4.1 million square kilometers on Tuesday, matching minimums set in 2007 and in 2016, according to the Colorado-based NSIDC.

It will take a few more days to know whether this year’s minimum has been set and the freeze season has started, Serreze said. Total ice extent can waver up and down at this time of the year because of shifting winds and a contest between freeze at the highest latitudes and continued melt in the more southern parts of the Arctic, he said.

This year’s minimum extent has no chance of matching the record-low 3.4 million square kilometers (1.32 million square miles) hit in 2012, Serreze said. Still, it fits into a trend to more open water over longer periods of the year, he said.

All that open water reinforces the warming cycle in the far north, strengthening the phenomenon known as Arctic Amplification, he said.

When waters lack ice cover, they absorb more solar heat, he said. “You’ve got to get rid of all that heat,” he said. “Where does that heat go? Up into the atmosphere.”

While annual minimums are useful markers for long-term trends, the expanding durations of open water are turning out to have more immediate significance, said Rick Thoman, climate scientist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

That is especially the case for the waters off Alaska — the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas — where ice has been especially scarce, even in the past winters, he said. The official Arctic-wide minimum extent is only part of the picture, he said.

“For Alaska, it doesn’t make much of a difference if it’s No. 1 or No. 4. There hasn’t been any ice anywhere near Alaska for a very long time and the water that’s there is extremely warm,” Thoman said.

In the waters off northern and northwestern Alaska, sea-surface temperatures were generally running 3 to 6 degrees Celsius (5.4 to 10.8 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal during the second week of September, according to data gathered by ACCAP.

Sea surface temperatures around Alaska remain above normal. Offshore North Slope departures are extreme: Wainwright to Prudhoe Bay 5 to 7C above normal. Storminess in the Bering Sea has lowered departures, especially Bristol Bay region. #akwx #sst @Climatologist49 @amy_holman pic.twitter.com/zZo6IQYr3E

— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) September 14, 2019

That sets the stage for a delayed freeze season, he said. “We can be absolutely certain that freeze-up in the Beaufort, Chukchi and at least the central Bering will be late,” he said.

Delayed freeze likely means a warmer-than-normal fall and, when the winter freeze arrives, ice that is thin and more susceptible to midwinter meltdowns similar to those that occurred in the past two years in the Bering and the Chukchi, he said.

The past years’ winter ice loss may have been highly unusual, but repeat occurrences could become more common if southerly winds return, Thoman said.

“I think you’ll see the big collapses like we’ve had in the past two years. That requires that sustained southerly flow. We won’t see that every year,” he said.

Thoman noted that with the exception of the extreme low in 2012, annual minimums over the past decade have been generally in the same ballpark.

That is because the very high-latitude ice, unlike ice at lower Arctic latitudes, has relatively brief period of the year when there is direct sunlight shining on it and causing melt from above, he said.

“We have melted all the easy, low-latitude ice now,” he said. Melting out ice at the highest latitudes will require a different process, he said. “That’s going to come from the ocean. That’s going to come from underneath,” he said.

Serreze, too, said the highest-latitude ice has lingered despite widespread melt elsewhere in the Arctic. At those very high latitudes — for now — there is still multiyear ice that survives melt seasons, he said.

But more changes are expected in the future, he said.

“We are kind of in new territory,” he said. “We have not been here before, so every year we’re learning.”