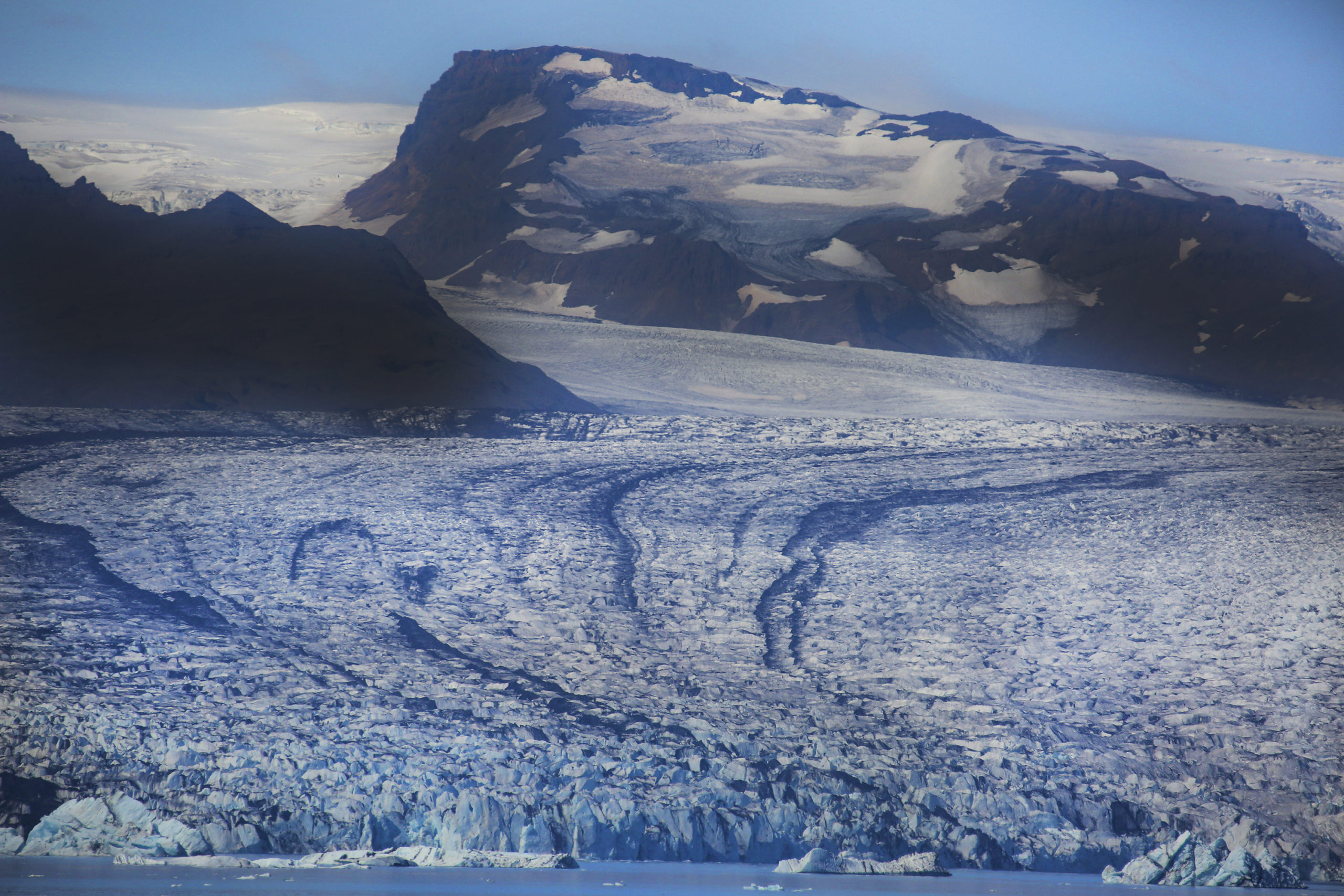

An unusually cool ‘blue blob’ in the North Atlantic is slowing glacier loss in Iceland

The area of cold water will likely persist until the 2050s — after which ice loss is expected to again accelerate.

A patch of unusually cold water in the North Atlantic Ocean, known as the “blue blob,” could forestall some of Iceland’s glacier melt in the next three decades, a new study says.

The cold water, south of Iceland and Greenland, is creating more snowfall over Iceland, replenishing the island’s glaciers as they melt and run off.

The cold blob is expected to linger until the mid-2050s, granting a temporary reprieve against glacial melt, according to the study published in Geophysical Research Letters.

When the waters eventually warm, however, the melt is projected to accelerate once more, with one-third of Iceland’s glaciers disappearing by the turn of the century.

[Time-lapse footage shows the dramatic retreat of a glacier in Iceland]

After receding steadily from 1995 to 2010, something unusual happened to Iceland’s glaciers in 2011 — the ice loss was suddenly cut in half, from an average of 11 gigatons to 5 gigatons of ice lost per year.

Researchers found that the “blue blob” was bringing cooler air to Iceland and causing more snowfall, offsetting some of its melt.

“Iceland is really influenced by the ocean surrounding it,” said Brice Noël, a climate modeler focused on the Arctic at Utrecht University and lead author of the study. “The cooling in the blue blob has a direct impact on the temperature of the glaciers.”

Glaciers tend to remain in equilibrium when new snowfall equals runoff from melting. When more ice melts than is replenished by snow, then they lose mass.

The study blends climate models with field research to determine that ice loss has slowed in recent years and may continue to do so as long as the blob exists.

The models used a scenario of rapid warming. “Even with strong warming, this blue blob would still persist,” Noël said.

“But this is only temporary because afterwards, warming in the blue blob starts again and then the mass loss would accelerate again. And we could predict that about a third of the total ice volume would be lost by the end of the century,” he said.

It’s possible the blob is also affecting the southern part of Greenland’s ice sheet, but more research would need to be done. So far, no effects from the “blue blob” have been recorded for Greenland or Svalbard.

The exact reason for the blob is not known, though it is thought to be related to changes in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, also known as AMOC. The current brings warm water up from the tropics, but it may be weakening in a changing climate, research indicates.

“If this is weakening actually, then you have less heat that is transported to the Arctic, and that could lead to this blue blob formation,” Noël said.

Changes to AMOC, especially in the Arctic, could have widespread effects on global weather systems.

Swift action on climate change, however, could make the blob last longer, and it could prevent ice loss acceleration in Iceland and elsewhere.

“The main message here is still clear,” Noël said. “We really need to try to curb the warming as fast as possible, because that will only be for the good of these glaciers — the less warming you have, the less melting you will have.”