An extensive new map collection sheds light on Greenland’s political history

From Dutch whalers to Danish colonizers to U.S. military forces, maps of Greenland were usually drawn for strategic reasons.

Maps are mirrors of the ambitions of the mightiest and portraits of their makers’ dreams — and that’s just as true in Greenland, the world’s largest island, as anywhere else.

If you want to understand Greenland’s place in the world from past to present, from the imperial visions of Europe’s kings to Danish colonization to the strategic interests of the United States, the island’s cartography offers arresting insights. And few, if any, knows the history of Greenland’s cartography more intimately than the Danish geographer, geologist and historian Henrik Dupont.

For 37 years he worked in the Department of Maps and Photography at the Royal Library in Copenhagen, and he has now concluded an arduous search through numerous libraries and archives for all traceable maps of Greenland ever produced.

Such a collection has never been available before. The creator of a previous collection of Greenland maps, the ”Cartographia Groenlandica,” got as far as 1576 but then died. Dupont’s collection reaches further back into history and also forward to the zoomable electronic military maps currently in production in Copenhagen on the basis of — among other material — satellite photos provided by the U.S. security agencies.

Dupont has studied a dizzying number of blurry sketches, crafty drafts and full-blown multi-colored maps from the travels of the Greeks in classical antiquity to the strategic maps pursuing Greenland’s proximity to the Soviet Union — and now Russia. A curated selection published in October in Denmark bears the title “Kortlægningen af Grønland” or “The Mapping of Greenland.” The hefty and colorful book is, for now, only available in Danish.

The Dutch whalers

When we met to talk, Dupont stressed that he would like in particular to correct the faulty conception that it was almost exclusively intrepid Danes who were from the beginning the foremost mappers of the island.

“The mapping was Dutch, British and American in all of Northwest Greenland and British, German and Norwegian on the East Coast. It is important to understand this, so that we arrive also at a proper Danish understanding of Greenland’s history,” Dupont told me.

Scandinavian settlers came to Greenland around the year 1000 from Iceland, a young nation closely connected to the Danish-Norwegian kingdom. In Denmark, these early settlers are still considered part of our national heritage.

From 1721, missionaries answering to the Danish king began a process of colonization that ended only in 1953, when Greenland became an integral part of Denmark. Today, Greenland enjoys considerable political autonomy, but remains part of the Danish realm; Greenlanders are Danish citizens. The responsibility for the mapping of Greenland’s open land still rests with the Danish authorities, but the sketching of Greenland’s geography was certainly not always done by Danes.

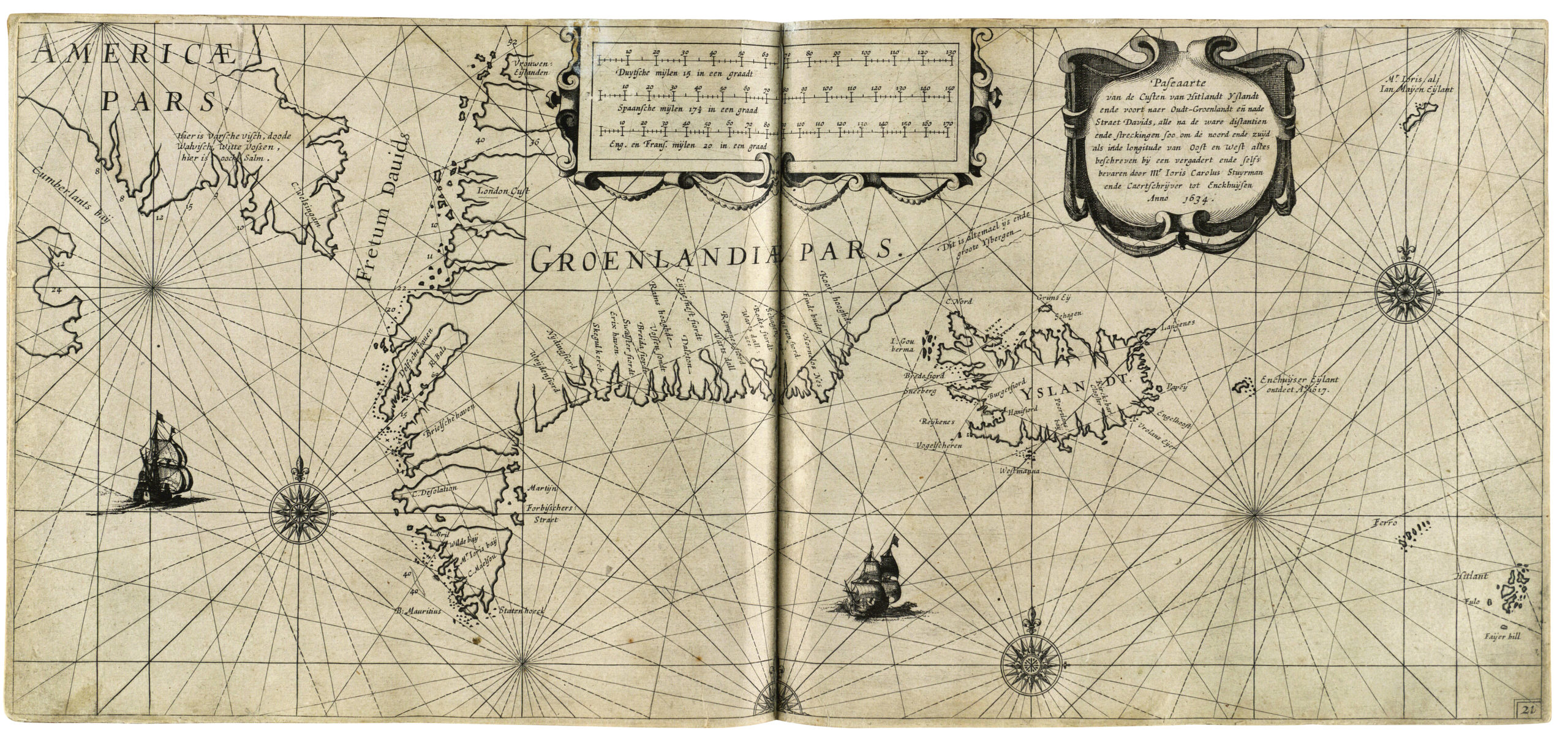

“The navigators of the Dutch whalers were particularly competent cartographers. They dominated cartography all the way up to the days of Hans Egede (the first Danish missionary to settle in Greenland, ed.) in the 18th century. The geometry and trigonometry of modern surveying surfaced in the Netherlands, and the Dutch were able to map large areas with relatively few measurements,” Dupont told me.

Portuguese and British explorers drew the first sketchy maps of Greenland’s western coastline during their unsuccessful quests for a northern passage to Asia, while Dutch whalers made maps for a profitable industry. Whale blubber was melted and used in street lamps as well as in homes in Europe. The maps of Greenland served mercantile goals, not military, as in most other corners of the world.

In his book, Dupont explains how one of the best Dutch cartographers of the time, Joris Carolus, served as navigator on several hunts along Greenland’s west coast. His “Pilot Book” from 1634 became “dominating for the mapping of Greenland throughout the rest of the 17th century,” as Dupont writes.

Greenland, the greater polar regions and the North Pole became objects of intellectual interest as a new world view took hold in Europe. The cartographers were the first to embrace a view of the known world that took its point of departure from above the globe, looking down on Earth — and preferably from a center point above the North Pole. As British scholar Michael Bravo, head of Circumpolar History and Public Policy research at Scott Polar Research Institute explains in his pivotal “North Pole – Nature and Culture” the new perspective aided the development of new tools for navigation that helped expand European empires, trading companies and other components of what we know today as globalization.

The reading of shadows

Greenland’s own inhabitants hunted on and explored most of their immense island long before the first Europeans passed by. The first wave of Greenlanders wandered from North America across the narrow ice-covered strait to the very north of the island. They traveled along Greenland’s coast line both eastwards and southwards. They left no known maps, but they mastered, as none before them had, the art of traveling across Greenland’s vast tracts of land and ice.

“I am deeply fascinated by the geographical knowledge that must have been present in Greenland during the 3-4,000 years before the Europeans arrived. The mapping in their minds must have been extraordinary. They were not dependent on any maps on paper on their sledges or kayaks,” Dupont said.

The first visiting Europeans were greatly aided by this Indigenous knowledge. Dupont assumes that Greenlanders aided even the earliest Portuguese sailors as they drew their sketches, and in 1884, as First Lieutenant Gustav Holm became the first Dane to reach the remote Ammassalik settlement on Greenland’s East Coast, local experts assisted his mapping by carving in wood precise profiles of the regional coastline. These are now treasured items at Greenland’s National Museum.

“They read the seasons of the year, the constellations of the stars, the tides of the sea, the ocean currents, the position of the Sun and the Moon. The shadows of the mountains helped them understand what lay behind the next outcropping or reef,” Dupont told me.

Cosmic architecture

Despite the local assistance, European mapping of Greenland battled for long with conflicting conceptions of the end of the world, its inhabitants and its relation with the divine.

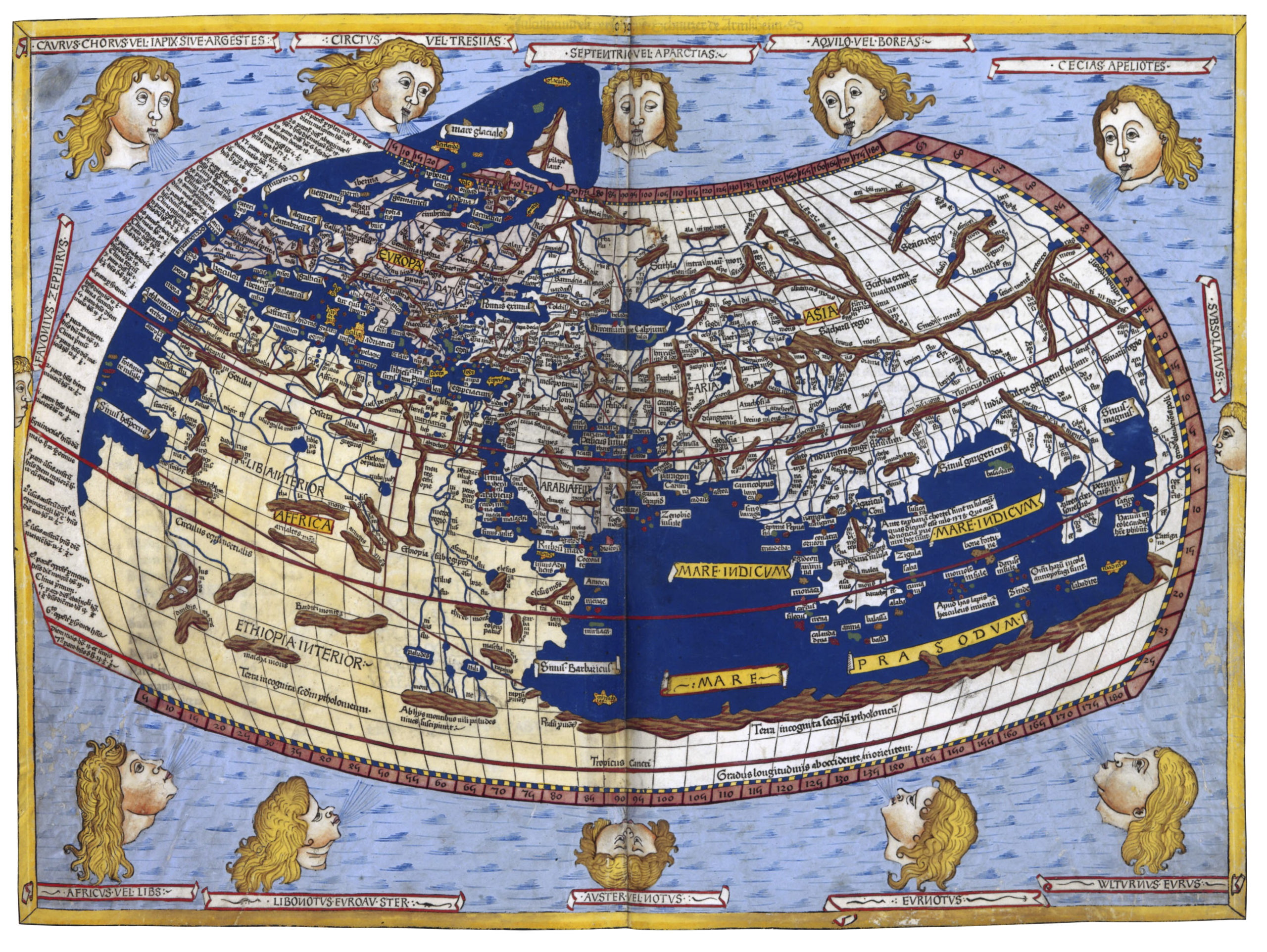

To the Greek and Arab astronomers the poles were, as Michael Bravo writes, “at the heart of the architecture of the entire cosmos.” But on the first maps of the world from approximately year 125 by Ptolemy, the Greek leader of the famous library in Alexandria in Egypt, the polar regions still appeared as “pure fantasy-regions that were, according to legend, inhabited only by strange creatures,” as Dupont writes in his new book.

In 1595 the Dutch cartographer Gerhard Mercator drew a famous map of the Arctic with the North Pole starring as a magnificent mountain of iron, ringed by four continents and four oceans that flowed towards the center of the Earth through an entrance at the foot of the pole mountain.

Greenland’s debut

Meanwhile, in 1427, Greenland had had its debut as a named entity on a European map. It happened on an updated version of a map of Ptolemy’s that itself was reportedly made on the basis of a separate map by Claudius Clavus. Claudius Clavus was Danish, born in Denmark in 1388, a theologian who for years lived in Rome where he shared his knowledge of Scandinavia, Iceland and Greenland.

In 1482, on another Clavus-inspired update to Ptolemy’s maps, Greenland appeared for the first time as a place inhabited by humans. Clavus’ knowledge of the Greenlanders had inspired a whole new understanding in Europe of the boundaries of human life: The polar regions were no longer portrayed as uninhabitable.

Clavus probably also drew maps himself, but if so, they have never been found — a fact that still has political implications. Legend has it that it was perhaps King Erik VII of Denmark that ordered Claudius Clavus’ mappings; Erik was a foster son of Queen Margrethe I, who ruled over all of Scandinavia for a long time.

If King Erik’s direct involvement was to be proven, it could support the idea that Danish kings eagerly embraced Greenland as part of their kingdom and as an integral part of the Danish domain earlier that previously believed. To some in Denmark, this interpretation of Denmark’s long-standing connection to the North Atlantic indicates that Denmark is still entitled to a degree of belonging in Greenland. That’s a reading of history that is, of course, disputed by many in Greenland.

Dupont has not been able to solve the riddle of Claudius Clavus:

“We still don’t know if Erik was involved. We only know that it was most likely Clavus — a Dane — who made the first map where Greenland is mentioned by name,” he told me.

Sovereignty

Later Danish mapping in Greenland has often been inspired by Denmark’s quest for sovereignty over Greenland. Jeppe Strandsbjerg, a Ph.D. lecturer who works at the University of Greenland and the Royal Danish Defense College, recently described this connection in Kortlægning og suverænitet i Grønland (“Mapping and Sovereignty in Greenland”, the Danish Institute for International Affairs) and Strandsberg draws support for his findings from Dupont’s collection of Greenland maps.

In his report he explains how the emphasis on sovereignty and military aims by those mapping Greenland “dates all the way back to 1605 when the first small topographic maps of Greenland served to signal Denmark’s sovereignty. Later, during the Second World War, the U.S. began mapping in order to make Greenland usable as a strategic military resource. As Greenland began to take responsibility for Greenland’s own development and asked for better maps, Denmark’s mapping came to a halt.”

In the 1930’s the political nature of mapping in Greenland became particularly apparent when Norway claimed parts of East Greenland. This led to a dispute between Denmark and Norway so deep that a resolution was only arrived upon through the The Permanent Court of International Justice in the Netherlands.

To convince the court, the Danish government dug into the archives to find proof of Denmark’s endeavors to defend, explore and map Greenland.

“They found an incredible lot of stuff. Mapping is used to cement how far your power extends and what you own,” Dupont told me.

At court, Norway emphasized that the Danish kings for centuries were unaware of Greenland’s precise contours, since Greenland, Svalbard and North America were most often amalgamated into misty and amorphous unknowns. No early maps gave any real sense of Greenland’s outer reaches.

For their part, the Danish authorities hunted in particular for one specific map. They believed that a map had been drawn in 1761 by the Danish whaler Volquard Boon of Scoresbysund, a widespread system of fjords in Northeastern Greenland. This was precisely the region that Norway now claimed. If found, the map would prove Denmark’s case and repel Norway’s.

“They tried really hard to find Boon’s map of Scoresbysund. They wrote some 50 letters to institutions and private individuals, but they never found it,” Dupont said.

Denmark convinced the court anyhow. In 1933 Denmark was accorded full sovereignty over all of Greenland, supported not the least by records of mapping and discovery.

The race to map

No maps by the first Scandinavian settlers in Greenland have been found, but there were plenty of later Danish contributions. In 1605, King Christian the 4th sent an expedition to Greenland, where its British navigator James Hall drew maps of the coastline about where the towns of Sisimiut and Nuuk, the capital, are now situated.

In 1629 Jens Munk, a Danish sea-captain, drew a map of South Greenland as he endeavored to find a sea passage to Asia. His attempt ended in near disaster, almost all members of his crew perished, but Munk returned to Copenhagen with his map. His king, Christian IV, also hired Joris Carolus, the Dutch cartographer, to teach aspiring Danish navigators.

In the 18th century, Hans Egede, the first missionary to settle in Greenland, and his sons, drew maps along Greenland’s west coast, and in the 19th century Danish mapping became more systematic in the hands of the expanding Danish colonial administration.

The Danes, however, were not alone. The U.S., Great Britain, Norway, Germany and others invested in Greenland’s exploration and mapping. All across the Arctic, national borders were blurry and important questions of sovereignty remained unanswered. Numerous islands, straits and lands in Greenland were named by foreign expeditions and in the middle of the 19th century, the U.S. Secretary of State William Seward suggested that Washington should buy Greenland from the Danish King.

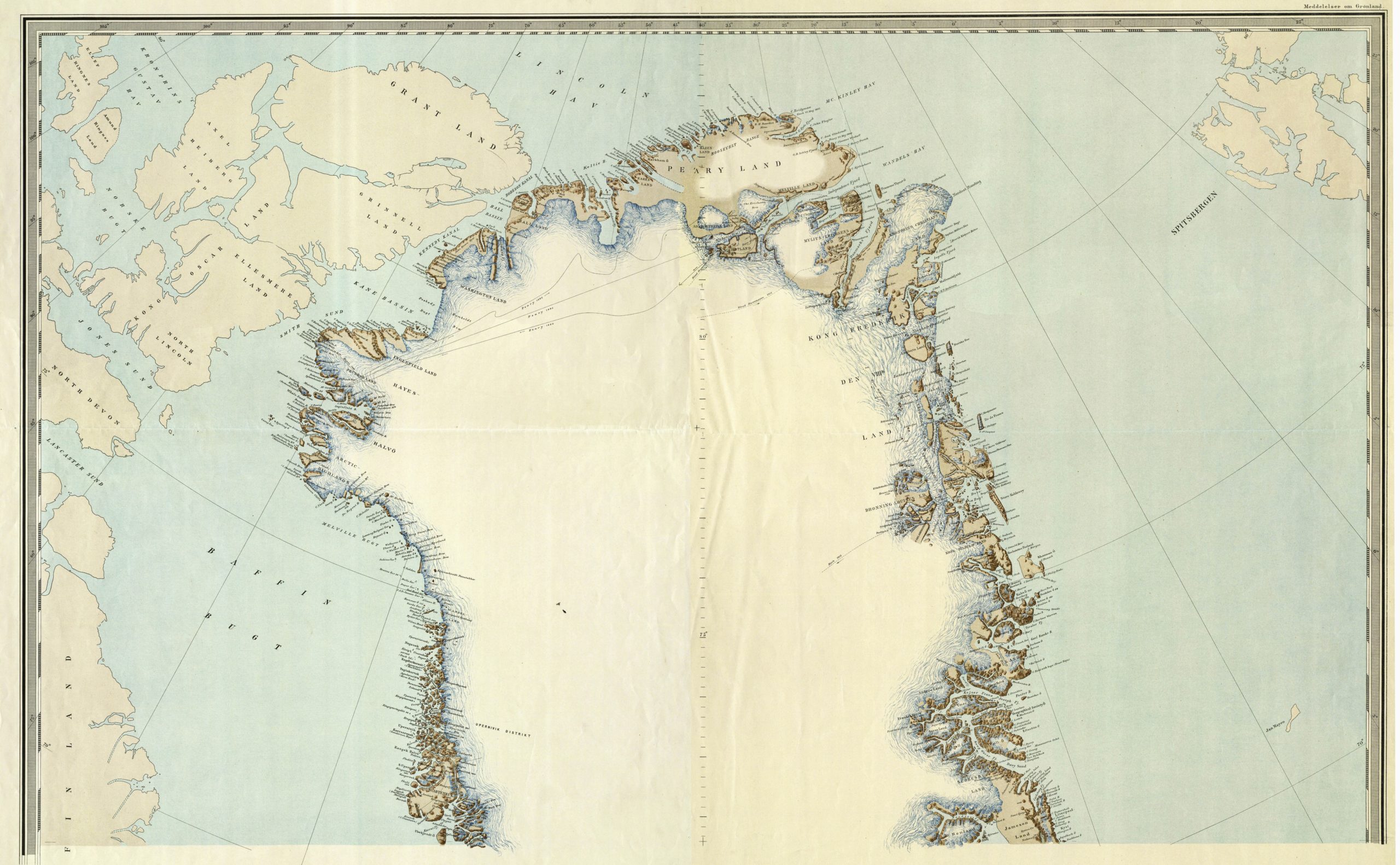

The need for more precise demarcations was pressing and in 1921 the Danish government declared that all of Greenland was now under Danish sovereignty. A series of expeditions by Danish explorer Knud Rasmussens had strong royal support and a large Danish expedition to North East Greenland from 1906 to 1908 resulted in maps of the last, uncharted sections of Greenland’s coastline. Three men lost their lives, but their mapping lived on.

U.S. explorer Robert Peary had long claimed that Peary Land, a large part of Northeast Greenland, was an island and potentially American property, but his claim was now solidly reputed. The maps from “The Denmark Expedition” clearly showed that Peary Land is an integral part of Greenland.

Secret maps

During World War II the Americans came back. Dupont believes that the U.S. defense forces drew maps of much of Greenland, but on this score his research hit a wall.

“We know that the Americans did aerial photography of all ice free areas of Greenland, but many of the maps are still classified and not available,” he told me.

After the war renewed Danish mapping supported civilian urban developments and explorations for minerals in several parts of Greenland. From the 1970s, however, as the Greenlanders took over still more political control of their own affairs, Danish mapping came to a halt, even if the need for maps was pressing. Greenland’s own surveying agency, Asiaq, began producing the most urgently needed maps of towns and settlements, but the main bulk of the open land was only subjected to very limited mapping.

Danish mapping only took speed again after 2012, a process that coincided with negotiations between Nuuk and South Korea about possible Korean help in the mapping of Greenland. The unusual contacts with South Korea — a far-away foreign power — never led to actual mapping, but, as Jeppe Strandsberg explains in his report, they underscored Greenland’s impatience.

Today, Denmark, Greenland and the U.S. all contribute to different parts of what is so far the most ambitious effort to create maps of all of Greenland’s ice free areas, a total of 450,000 square kilometers. This modern mapping of Greenland has been under planning and implementation in Denmark for more than a decade.

Once again, Greenland is of great strategic importance for the defense of the U.S. and large quantities of U.S. satellite photography are used for new military electronic and zoomable maps of Greenland. This part of the project is initiated and led by the Danish defense and draws on well-established international collaborations with the U.S. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency at its core. The U.S. provides satellite photography for the military maps of Greenland but is not otherwise involved in the mapping.

Aided by the military mapping, the Danish civilian authorities produce a range of electronic civilian maps in close collaboration with the authorities in Nuuk, Asiaq Greenland Survey included, thus meeting a dire need for updated and detailed maps of Greenland’s vast open lands.

More mapping is most certainly to come, but for now Dupont’s book beautifully summarizes it all from past to present. The maps of old reflected the ambitions and alliances of their time and — as Dupont aptly describes — so do the new.

This article has been fact-checked by Arctic Today and Polar Research and Policy Initiative, with the support of the EMIF managed by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Disclaimer: The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the author(s) and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.