Alaska’s North Slope has plenty of undeveloped oil left, a new estimate finds

Even with new discoveries, there's still a lot of oil in Alaska's biggest oil province, the U.S. Geological Survey says.

Four decades after oil began flowing from Alaska’s North Slope, a new resource assessment says there is plenty more oil yet to be discovered.

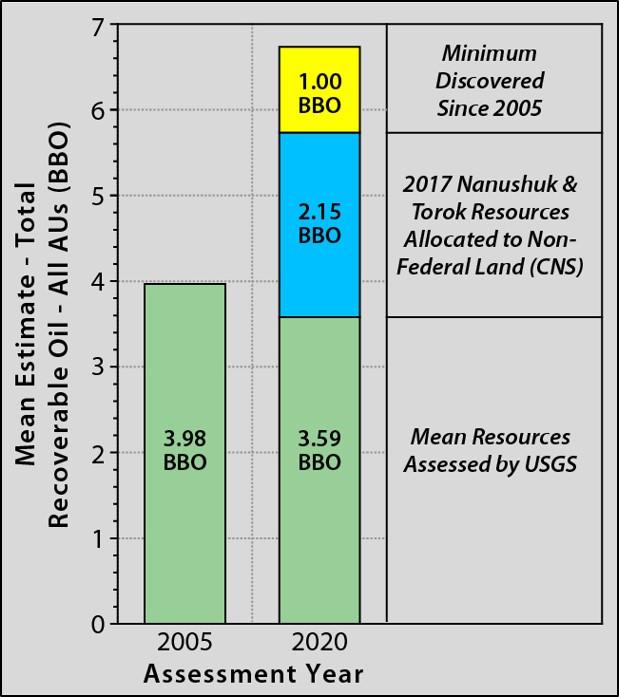

The Central North Slope — the state-owned territory that is the core area of existing development — holds another 3.59 billion barrels of yet-to-be-discovered but recoverable oil, according to a mean estimate calculated by the U.S. Geological Survey in its newest resource assessment.

The UGSG resource estimate, released on Jan. 23, shows that much life remains for the oil-producing region, the agency’s leader said in a statement.

“Alaska is synonymous with energy, and this assessment just reinforces that,” USGS Director Jim Reilly, said in the statement. “The State of Alaska and its industry partners have responsibly produced billions of barrels of oil from Prudhoe Bay, and we think there are still billions more in this region that can be produced.”

Nominally, the estimate of undiscovered Central North Slope reserves is lower than the estimate released by the USGS in 2005. Then, the mean estimate of yet-to-be-discovered oil in the Central North Slope was 3.98 billion barrels.

But since 2005, there have been important changes, said Dave Houseknecht, a senior USGS research geologist and the lead author of the new resource assessment.

About 1 billion new barrels have been discovered in the central North Slope since 2005, he noted.

More significantly, the USGS has separated out the Nanuskuk and Torok geologic formations, which are mostly on the western part of the North Slope, from its Central North Slope analysis, Houseknecht said.

A USGS resource assessment of those formations led by Houseknecht and released in 2017 had mean estimates for undiscovered but recoverable reserves totaling 8.8 billion barrels of oil, 39.27 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 489,000 barrels of natural gas liquids.

Those formations, particularly the Nanushuk, are the base for multiple recent discoveries and a flurry of North Slope exploration and development.

They are largely within federal territory, the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska west of state land, though they do extend eastward into state and federal land. Within the totals in the 2017 assessment, about 2.15 billion barrels of the undiscovered recoverable reserves in the Nanushuk and Torok formations are believed to fall within the geographic boundaries of what is considered the Central North Slope, Houseknecht said.

The new resource estimate for the Central North Slope does not include that Nanushuk-Torok complex, he said.

“Geologists like to assess by geologic borders rather than by land-ownership borders,” Houseknecht said. “The fact that they cross political borders for us, as geologists, is kind of irrelevant.”

In all, the Central North Slope has 3.59 billion barrels left to discover in non-Nanushuk and non-Torok formations, 2.15 billion that is within Torok formations, according to the mean estimates, along with the additional 1 billion that has been discovered since 2005.

Estimates of undiscovered North Slope reserves evolve as new information comes in. Updated information available through 3-D seismic surveys proved valuable in the new Central North Slope assessment, Houseknecht said. And as more exploration is conducted on the western side of the North Slope, additional information comes in from the companies’ work, he said.

For example, just days before the release of the new resource assessment, Australian company Oil Search Ltd. announced it struck oil at an exploratory well drilled at the Pikka prospect, which targets the Nanushuk formation.

There has been a flurry of such discoveries, Houseknecht said. “They keep rolling in,” he said.

If the new Central North Slope assessment provides a rosy outlook for more oil to be found, the case is different for natural gas.

The new mean estimate for undiscovered natural gas resources in the region declined to 8.9 trillion cubic feet, significantly less than the 2005 mean estimate of 37.5 trillion cubic feet estimated in 2005.

Even if the Nanushuk-Torok formation analysis is added in, the new natural gas estimate for the Central North Slope is lower now than in 2005, Houseknecht said. Under the 2017 assessment, the Nanushuk and Torok extensions into the Central North Slope geographic region had a mean estimate of 4.7 trillion cubic feet of undiscovered natural gas, he said.

The reduction in estimated Central North Slope natural gas reserves is due largely to a better understanding of natural gas formations in the Brooks Range foothills area, Houseknecht said. “They’re much more complex and much more broken up than was appreciated in 2005,” he said.

The North Slope already has about 35 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves, most of that in the Prudhoe Bay field. Those reserves are considered stranded. Despite decades of efforts and numerous plans that have been proposed over the years, there is not yet any market for that natural gas and no means of shipping it off the North Slope. The newest plan, reminiscent of Russia’s development of Yamal Peninsula gas fields, proposes liquefying the gas at a site just offshore of the coast and shipping it directly to markets in icebreaking vessels, skipping the expensive step of building an 800-mile pipeline to tidewater in southern Alaska.