Across Arctic North America, solar energy is gaining a foothold

The high costs of fossil fuels helps make solar energy attractive, despite some unique challenges.

Arctic renewable energy has the potential for a global impact, but stories of energy transformation in the region are often overshadowed. For the month of September, ArcticToday is launching a special focus on renewable energy in the Arctic and this piece is part of that coverage. Find the full series here, or subscribe to our daily newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter to be the first to read new installments.

Turning to the sun for power is environmentally responsible, helping to reduce fossil fuel emission and slow the rate of climate change that transformed the Arctic.

But in the northwestern Alaska community of Kotzebue, where Alaska’s second-largest solar array was just put into service in late June, there is an even more immediate concern: cost.

Because of geographical isolation and the need to import diesel fuel used in power systems, electricity is extremely expensive. That creates a powerful incentive to shift to renewable energy, said officials with Kotzebue Electric Association, the cooperative that just installed the solar array.

“Everybody wants to save the environment,” said Martin Shroyer, KEA’s general manager. Still, the driver is “probably economic first and environment second,” he said. And the biggest annual cost is diesel fuel, he said.

The new 576-kilowatt solar project, with its 1,440 solar panels, has already started reducing that cost, said Shroyer and Matt Bergan, a KEA engineer and manager of the solar project.

“So we’re burning less fuel as we speak,” Bergan told ArcticToday.

Solar energy might seem counterintuitive in a part of the world where the sun rises above the horizon for only briefly — or not at all — for long stretches of the year. But that cuts both ways. Extended summer daylight and sunlight reflecting off snow in late winter and spring help make solar energy successful in the far north, as a project in Old Crow, Yukon discovered.

And technological innovations, such as bifacial panels — some of which are installed in Kotzebue — can take extra advantage of the long Arctic summer days.

Solar arrays still need to be paired with energy storage or other forms of generation — such as wind and diesel in Kotzebue — but they can contribute a significant amount of energy in the Arctic.

With the addition of solar energy into the system, for example, KEA should consistently have at least 25 percent of its power fueled by renewables, Shroyer and Bergan said. The goal is to get to 50 percent, but hitting that rate will require more solar panels, more storage capacity and more work, Bergan said.

“I would say it’s several years down the road to achieve that 50 percent,” he said.

Kotzebue’s new solar array is the second-biggest in Alaska after the Willow Solar Farm in the Matanuska-Susitna Borough north of Anchorage. It is the largest in rural Alaska and the most notable in the Arctic region. It was made possible by grants from NANA Corp. (the regional Alaska Native corporation established under the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act), and the Northwest Arctic Borough, as well as some savings within the Kotzebue Electric Association.

KEA was an early convert to renewable energy. In the 1990s, it installed three wind turbines, devices that have helped reduce diesel use and costs over the years. But those turbines are now aged and getting close to being obsolete, a situation that was a factor in the decision to launch the solar project, Shroyer and Bergan said.

Wind energy is a good option in a lot of Alaska communities, a useful source of renewable energy, said Edwin Bifelt, the founder and chief executive of Alaska Native Renewable Industries, the contractor on the Kotzebue solar project.

Compared to solar, however, wind can have some disadvantages, said Bifelt, who is based in the Athabascan community of Huslia in interior Alaska.

“You have these huge, giant towers that you have to install and you have the constant cost of maintaining them,” he said.

A solar array, in contrast, is fixed in place and can provide energy for several decades, he said. And putting one up is “not super complex. It’s just a lot of labor,” he said. “There’s a lot of advantages to solar power in Alaska.”

Still, there are some complications to manage for when erecting solar arrays in Arctic sites like Kotzebue. Permafrost is one source of potential problems; solar arrays must be raised above the tundra surface to prevent thermal disturbances, while in the Lower 48, installers can simply place gravel pads right on the ground, he said. Depending on remoteness of locations, there can be high costs for bringing in materials, possibly by barge or air, he said.

This year in Kotzeubue, there was an additional complication: the coronavirus pandemic. There was regular and frequent testing of the crew, and that and other precautions created new tasks that taxed the work schedule.

While the Kotzebue array is now one of the biggest in the state, it’s just one among many sites where Alaskans are collecting energy from the sun to cut down on use of costly fossil fuels. Solar panels can be found around Arctic Alaska, though many are small systems serving individual homes or buildings.

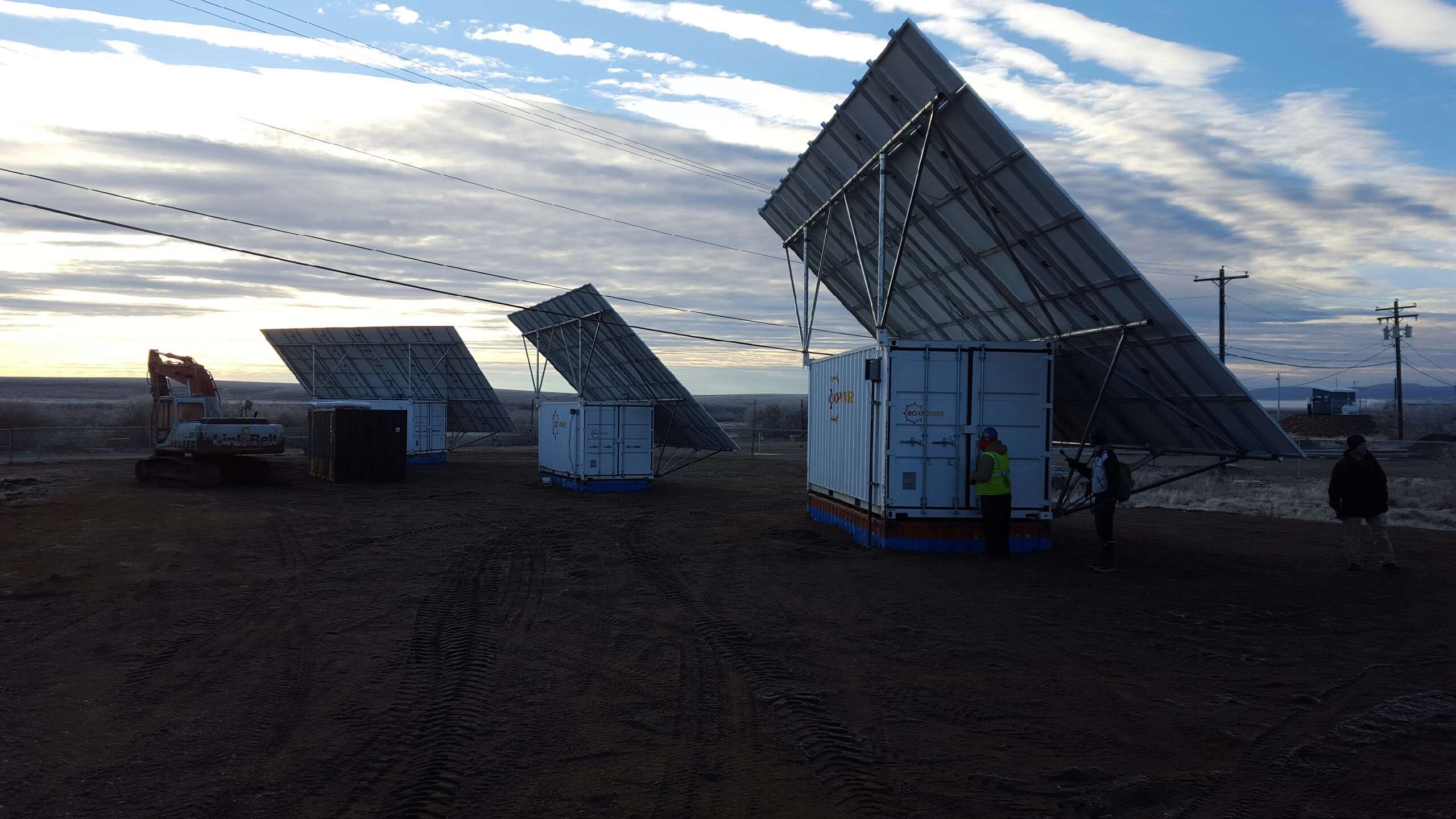

Another site now using solar energy is Buckland, an Inupiat community of about 500 in the Kotzebue region. The village began tapping into solar energy in 2018, thanks to a modular array created by the California company BoxPower. The project was funded by NANA and the U.S. Department of Energy as part of a larger program to bring solar energy to the region’s smaller communities.

Rural Alaska is plagued by extremely high energy costs — for electricity, heating and transportation. The need to ship in liquid fuels is a major driver of those high costs, according to an analysis by the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute for Social and Economic Research. The Alaska Village Electric Cooperative, which serves 58 communities spanning a region from the Chukchi Sea coast to the Kodiak Island Archipelago in the Gulf of Alaska, has quantified that cost driver, estimating that it amounts to about half of the price that customers pay for electricity.

The end result is a customer price in much of rural Alaska that is 40 cents a kilowatt-hour and can soar much higher. “People can’t pay that or continue to pay that,” Bifelt said.

Political forces are adding to the incentive to switch from imported diesel to locally generated renewable energy, he said. The state maintains a Power Cost Equalization fund to prevent rural energy costs from skyrocketing even higher than they are, but that fund is now vulnerable, he believes.

Last year, Gov. Mike Dunleavy struck down the legislature’s entire annual PCE funding, part of a series of sweeping budget vetoes. A few months later, after a special legislative session and much public outcry, the PCE funding was restored, but there are concerns in rural Alaska that the reprieve is only temporary.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty about it,” Bifelt said. “It’s at the whim of the legislature, so who knows how much longer that program could last?”

PCE has been an important cost buffer for rural Alaskans. In Kotzebue, for example, the current customer cost of electricity is 22.77 cents per kilowatt-hour with PCE funding; without it, it is 43.46 cents per kilowatt-hour, according to KEA’s current breakdown. The national average is about 13 cents per kilowatt-hour, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

For rural Alaska, there is a cost of fossil-fuel reliance that goes beyond electricity rates: environmental hazards. One example occurred recently in the northwestern Alaska village of Shungnak, where a delivery mistake caused about 15,000 gallons of heating oil to overflow a tank. The spilled fuel threatened the Kobuk River, which supplies the fish that make up much of the local residents’ diet.

Shungnak, home to about 275 people, is one of the next villages in line for a solar energy system, and Bifelt intends to submit a bid on that project.

There is a push for solar energy in the Canadian Arctic, too.

Shroyer and Bergan said KEA took lessons from Canadian experiences with solar energy. They pointed to systems such as those in Old Crow, the northernmost Yukon Territory community, and Colville Lake in the Northwest Territories.

In Yukon, the Vuntut Gwitchin Government views the solar project as part of a broader plan that might include wind and biomass energy.

Last year, three months after declaring a climate emergency, the First Nations government set an ambitious goal. In an August 2019 resolution, the government declared that it intends to make Old Crow carbon-neutral by 2030. The solar project now in place “demonstrates the positive economic, environmental and social benefits of community-owned clean energy generation” and helps point the way to that goal, the resolution said.