A stringent isolation strategy has kept Greenland mostly safe from the COVID-19 pandemic

Greenlanders head to the polls next week to choose a new parliament in a country that feels almost back to normal, thanks to strict policies aimed at stopping coronavirus at the border.

NUUK — Last month, a 73-year-old woman was found dead in Sisimiut on Greenland’s west coast. The police suspected homicide. A forensic specialist from Denmark was summoned to assist the investigation — but what about the risk that he might bring coronavirus to Greenland with him?

All travelers to Greenland must test negative for the virus that causes COVID-19, remain in quarantine for at least five days after entering the country, and then submit to re-testing, before they are allowed to walk freely (I have just been through this routine myself).

And as anyone who has read a crime novel will know, a murder investigation cannot wait five days.

A solution was found, of course. Many months ago Greenland’s health authorities had placed advanced testing equipment, bought in the U.S., in most larger towns. A coronavirus test can be done and analyzed in less than two hours if absolutely necessary.

The traveling forensic specialist could go right ahead with the autopsy, illustrating in this somewhat macabre way how Greenland’s strategy to fight the COVID-19 pandemic differs radically from that of most other countries.

In the U.S., Canada, Denmark and most of the rest of the world, government authorities are ready to tolerate some level of infection (if preferably a low one) as long as healthcare systems are not overwhelmed.

Not so in Greenland.

The health care authorities here aim to detect, catch and stamp out every single case of infection, before the infection spreads. Since the pandemic began in early 2020, 31 cases have been detected, pursued and isolated in Greenland; all 31 men and women are now well. As I write this, no one has been hospitalized in Greenland and all potential chains of infection have been broken and closed. The health authorities pursue a strategy of zero tolerance with broad political and public support.

Greenland closed off

To sustain this approach, the world’s largest island has been almost shut off from the rest of the world. Since December, only strictly necessary and formally approved travels to Greenland are allowed. No international air travel to Greenland is permitted, save a few carefully controlled flights from Copenhagen by Air Greenland, the publicly owned airline. Doctors and nurses, essential travels by government officials, next-of-kin attending funerals and a few journalists are given approval, but only very few others.

Furthermore, travelers to East Greenland and large portions of the north and south of the island have to spend at least five days in quarantine elsewhere in Greenland before heading to their final destination. That’s because Greenland’s chief medical officer Henrik L. Hansen, head of the National Board of Health, has deemed it next to impossible to combat any spread of the coronavirus in the more remote regions.

I find Hansen at his office in an old brown wooden house, which once served as the first ever U.S. consulate in Greenland during World War II. The low structure is close to Nuuk’s historic harbor, which is normally popular with the tourists but now deserted.

“In the beginning of the pandemic, I didn’t expect that we could avoid the spread of corona we saw elsewhere. But against my expectations we were able to contain it. We had a unique chance, since we live on an island, and when we succeeded in the first instant, it seemed logical to continue. When the time comes to evaluate, I think that we will find that those nations who have tried to keep the infection completely contained, did best,” he says, pointing at other island nations with related zero tolerance strategies like New Zealand, Taiwan and Isle of Man.

Complex logistics

The core of the challenge in Greenland is the scarce resources of the public health care system; there are no private hospitals or other health care facilities in Greenland.

“If we suddenly get a lot of ill people, our capacity to deal with them is very, very small. We can only treat seriously ill people in the small intensive care unit at the hospital here in Nuuk,” Hansen tells me.

Queen Ingrid’s Hospital has a total of four intensive care beds and any larger number of patients, even if they do not need intensive care, might soon exhaust ressources. Hansen fears in particular that not enough nurses and doctors will be at hand.

About a third of Greenland’s 57,000 citizens live in Nuuk, the remainder in some 70 towns and hamlets on the enormous island, and not two of these settlements are connected by roads or rails. If a coronavirus patient gets seriously ill anywhere but Nuuk, he or she will have to be flown to Nuuk. But such transport will demand extraordinary efforts. Any risks of infection among the flight crew, the airport personnel and the accompanying health professionals will have to be stringently dealt with. And if the weather turns ugly, any flying might be impossible for days on end.

“It will be extremely complicated. For the sake of the patient it has to happen very quickly, but everything takes time in Greenland,” Hansen tells me.

Elections takes place in Greenland next week for Inatsisartut, the parliament, as well as for Greenland’s five municipal councils and for ward councils. A large number of candidates have been campaigning basically unhindered by the pandemic, and not one of them has made the coronavirus strategy a theme for debate. Since Hansen’s zero tolerance approach gradually turned into Greenland’s politically adopted strategy last year, there has been virtually no discussion of its merits.

I track down Inga Dora Markussen, one of the two deputy chairpersons of Siumut, Greenland’s largest political party, and a former secretary general of the West Nordic Council. She has a firm idea why the zero tolerance approach seems to square with public sentiments:

“We are all aware of the limited capacity of our health care system,” she says. “But also, we are very closely tied to each other. In our small communities where everybody knows each other, everyone is hurt when somebody loses a relative. It just seems very natural to us to do whatever it takes to avoid infection.”

Others talk about the long history of deadly epidemics in Greenland. In the 19th century, large portions of the population were killed by pandemics brought by colonialists from Europe. Later, epidemics of the flu, smallpox and tuberculosis took heavy tolls.

No lockdown

Compared to the lockdowns in the U.S. and elsewhere, Greenland’s civil life is surprisingly undisturbed by the pandemic. Most here carry on with their daily routines as if there was no pandemic.

Early on in the pandemic, Greenland fought back with lockdowns, closed schools, bans on travel between towns and on the sale of alcohol. Hansen, who is Danish and served formerly as the chief medical officer of the Faroe Islands, worked hand in hand with Greenland’s political leaders to contain the disease. For a time in 2020, Nuuk was completely cut off from the rest of the world. But gradually most restrictions have been lifted.

The authorities still recommend keeping a distance of two meters between people, and there are warning signs and alcohol for disinfection of one’s hands in most shops. Indoor gatherings of more than 50 people need official approval and community halls, sports facilities and the like may hold only half the number of people they are designed for. But I shop and eat at restaurants without a care; not a face mask in sight. Greenland’s main annual sled dog race was successfully completed a few days ago. Hairdressers are busy, fitness centers are crowded and the kids go to school as usual. Most businesses continue with little disturbance. Perhaps most importantly, Greenland’s fishing industry, provider of more than 90 percent of Greenland’s export revenue and the main source of income for thousands of families continues apace.

Trawler crews flown in from abroad must spend five days in quarantine; this is cumbersome, but far from destructive for business. In construction, workers who fly in from abroad must work, sleep and eat on their own for five days; frustrating, but not a real obstacle.

Greenland’s tourism is hurting badly, but is not all gone. Like other people, Greenlanders are learning to make holidays in their own country, and in the broader context, tourism has not yet become significantly important to Greenland’s economy. Many tourist businesses suffer, but the tourism sector as such still supports the zero tolerance approach, even if it has a repeated request:

“We support the strategy, but the tourism sector needs a plan for the reopening of Greenland, so we know what to expect. Our international partners need to know, when they can count on us again. The guests are ready — also to quarantine in the wild,” says Mads Skifte, deputy head of Visit Greenland, the tourist council.

Hansen’s strategy has little opposition: “Broadly speaking all agree that a lockdown of our society like in Denmark would be more expensive for businesses and for our society at large,” he says.

Where coronavirus is hurting Greenland’s economy, it is not because of the internal restrictions, but because exports of fish and other seafood do not bring the same revenue as before. China has imposed wide-ranging restrictions on all imports of fish and seafood; that hurts, as China has become the largest single buyer of Greenlands fish and shrimp. After Brexit, Great Britain has imposed new tariffs on fish from Greenland and prices in the rest of the world are plummeting.

Exit strategy

Like in other countries, a public program of vaccination is underway in Greenland, even if it is delayed due to the doubts about the AstraZeneca vaccine that are troubling much of Europe. Greenland’s vaccine program aims first to reach the most vulnerable and then everyone beyond the age of 65. The campaign, however, takes shape according to local conditions: In the far-flung hamlets, for example, everyone is vaccinated at once, because it is too costly and cumbersome to travel more than strictly necessary.

“35 percent live in regions where we still have not vaccinated anyone,” says Hansen.

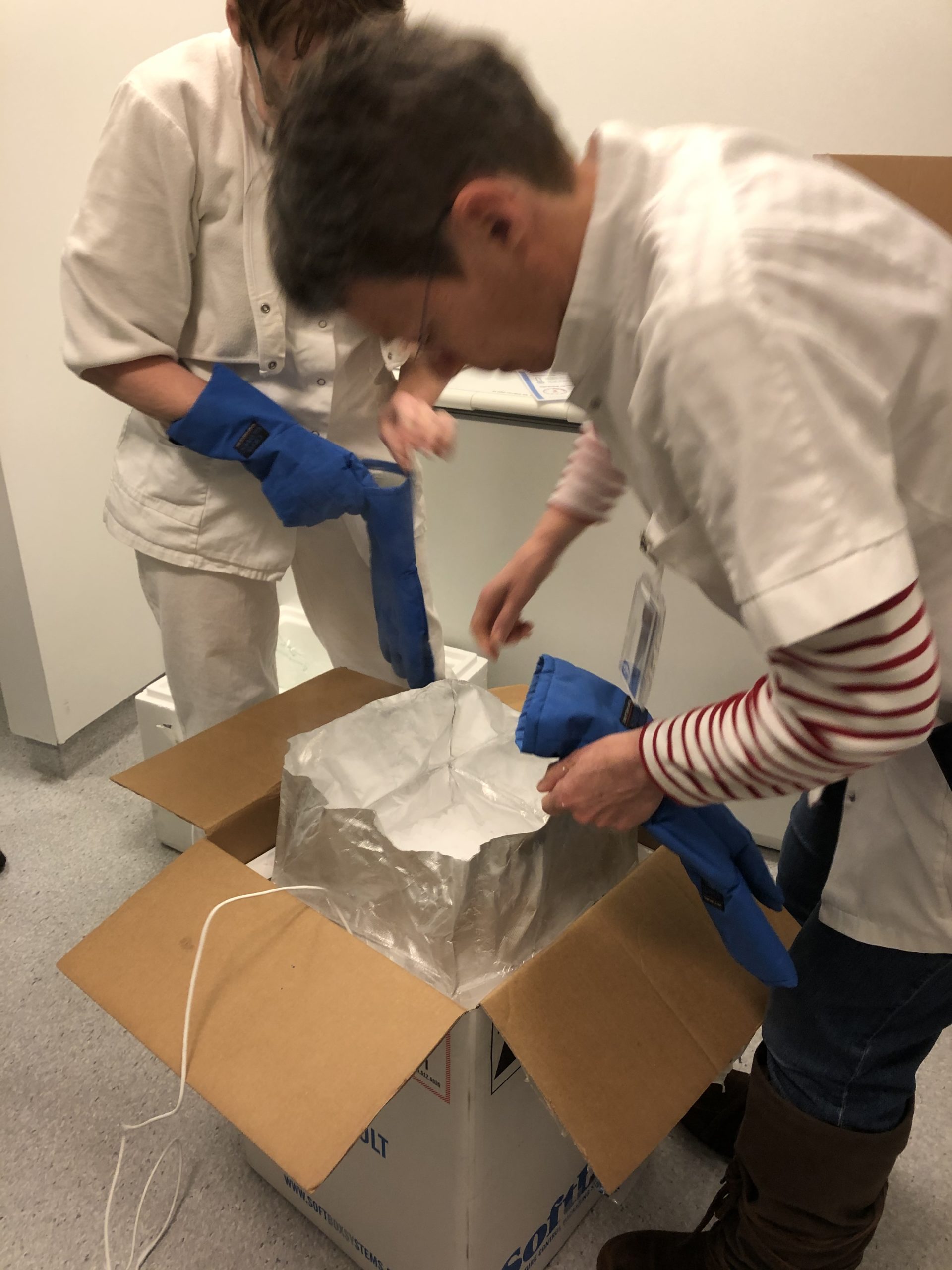

Vaccines arrive by plane from Denmark, which still holds sovereignty over Greenland. Since 1953, Greenlanders have been citizens of the Danish Kingdom with the same basic rights to health care — including vaccines against coronavirus — as Danes.

Some months ago, Kim Kielsen, Greenland’s premier, asked Denmark to provide a larger batch of vaccines up front. The plan was to make special efforts to vaccinate in Greenland’s more remote regions. But that request was turned down. Greenland will have to wait in line like everybody else.

Most vaccines are flown by air from Nuuk to their final destination in Greenland, but some are distributed by the naval vessels of Denmark’s Arctic Command in Nuuk. The grey warships have done so far two trips with vaccines and health care personnel; an extended operation in the south of Greenland is planned for April. A freezer to keep the vaccines at minus 80 degrees Celsius is on loan from the University of Greenland, and the operation has been politically approved. No one seems bothered that Denmark’s armed forces are once again involved in solving a serious problem in Greenland and the signals this might send about Greenland’s continued dependence on the old colonial masters.

And how then will the coronavirus situation look in Greenland a year from now?

Hansen is optimistic. Statistically, the restrictions on travels to Greenland, the quarantine and the re-testing will catch at least 80 percent of those who bring virus into the country, he says. So far, this has been sufficient to avoid uncontrolled spread of the infection and the vaccination program will further reduce the danger.

In the midst of the election campaign, the restrictions on travel were extended to May 2; zero tolerance will remain the backbone of Greenland’s corona efforts. Hansen and the rest of Greenland’s coronavirus task force is working on recommendations for the next phase. Eventually the winners of next week’s election will decide how precisely Greenland is to proceed.