A joint US-Russia aerial survey yields a new, large-scale picture of Chukchi polar bears

The project used coordinated aerial surveys and modeling to give scientists a much better understanding of the region's polar bear population.

Polar bears blend easily into their white ice-and-snow habitat, they move frequently in and out of the water and they can travel vast distances over remote and forbidding territory, blithely ignoring national borders. All that makes it difficult to count them.

But now sophisticated aerial surveys conducted jointly by scientists in Alaska and Russia has produced what is believed to be the best available estimate of the Chukchi Sea polar bear population, one of 19 in the Arctic.

Results from the survey project, published in the journal PLOS ONE, show the Chukchi population to be more robust than earlier estimated, ranging from 3,435 to 5,444 animals.

The estimate is derived from aerial surveys conducted from Alaska and Russia in 2016, part of a program initiated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. That compares to an earlier estimate of just under 3,000 bears, though that estimate came with wide margins above and below.

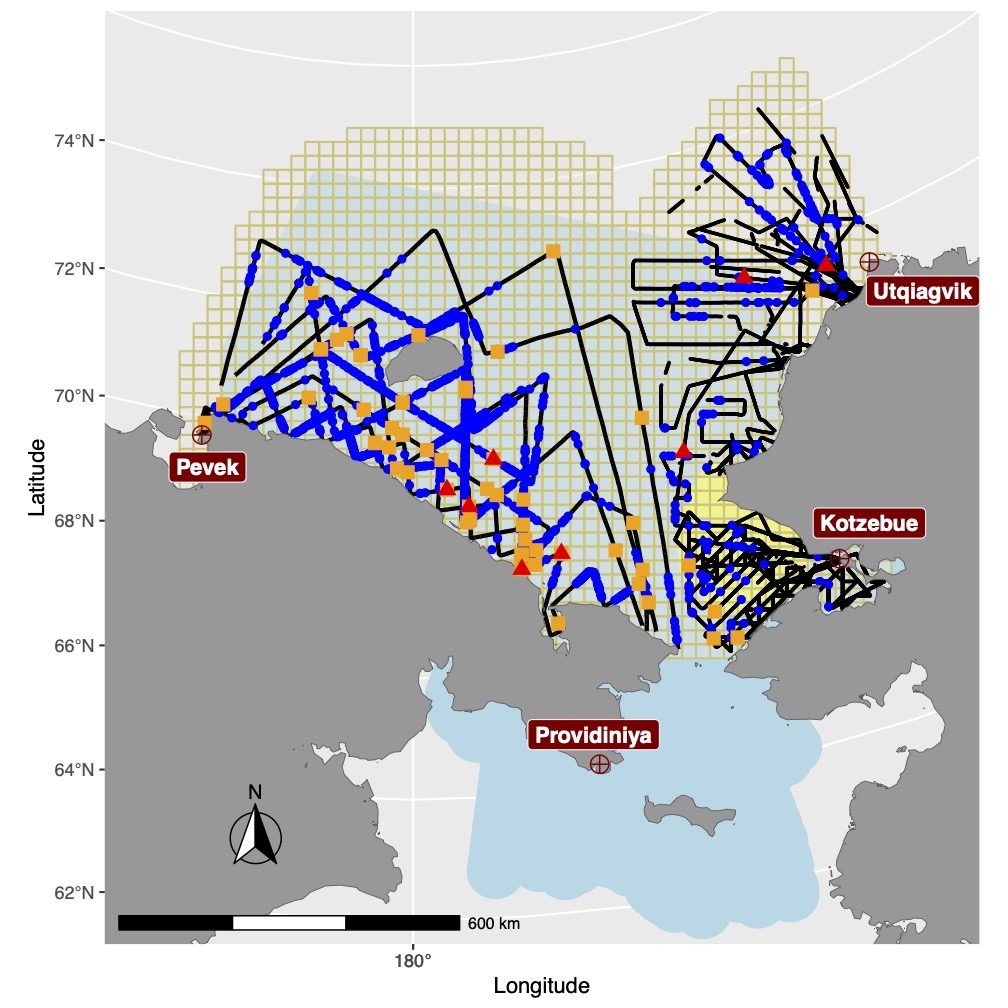

Previous aerial surveys of Chukchi polar bears had been limited to the U.S. side of the icy sea. This project, which was a cooperative effort by NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, some Russian organizations and an independent Russia-born consulting scientist based in Seattle, covered much more territory. The U.S. flights were conducted from Kotzebue and Utqiagvik in Alaska and Russian flights were conducted out of Pevek and Provideniya in Russia.

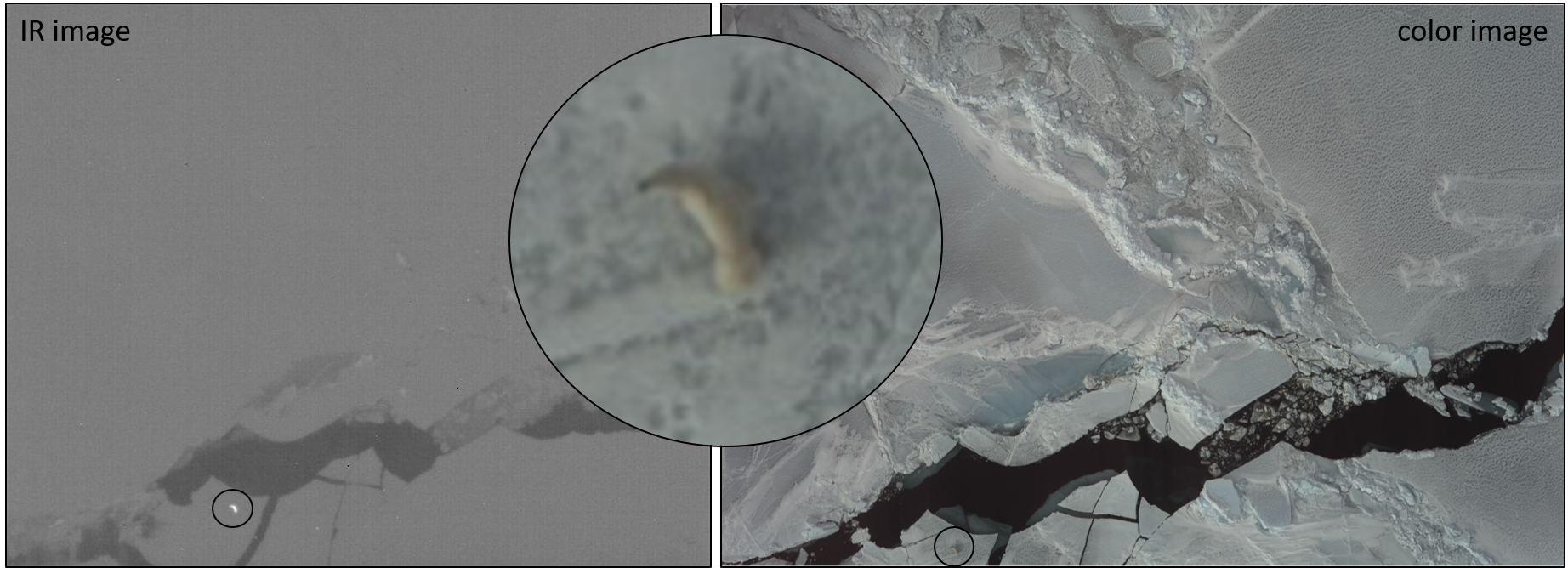

The project used infrared technology, aerial photography and modeling to estimate population and range for polar bears and for the ice seals that are their prey.

The study leader, NOAA’s Paul Conn, had high praise for the Russian scientists who worked on the project.

“They are very dedicated scientists trying to get a lot of things done with minimal funding,” said Conn, a research statistician at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “They’re great people. It’s one of those things: Governments disagree, but people get along, he said.

The international nature of the work did slow some of the analysis, however.

“They’re not really allowed to just hand us a hard drive of data. We kind of had to wait until their results were published in a Russian journal,” he said. That partly accounts for the long wait from 2016 until now for the release of the population information, he said.

Another glitch came in the form of technical difficulties with the thermal detectors used in the Russian flights, which meant some extrapolation and modeling, Conn said.

A far-ranging aerial survey project may be appropriate for polar bears, animals legendary for their long-distance travel. A bear in the Southern Beaufort Sea population, for example, was found to have traveled all the way from northern Alaska, where it was collared in 1992, to Greenland. That bear traveled 5,256 kilometers in the first year after she was collared, according to the data.

The Chukchi bears are no exception to the traveling behavior.

Several of the maternal bears that were captured and collared off Kotzebue spend their summers on Russia’s Wrangel Island, said Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Ryan Wilson, a co-author of the paper. Maternal Chukchi bears that the Fish and Wildlife Service has found off northwestern Alaska are likely to have denned on Wrangel Island

The aerial surveys do not provide the detailed information about body condition and other important factors that scientists get when they do live captures, sampling and collaring, he said. But they do provide other valuable information over wider scales.

“It gives you kind of a snapshot in time,” he said.

Avoiding the need for scientists to be on the ground is an important plus. Poor ice conditions in recent years have made it largely impossible for Fish and Wildlife Service biologists, who generally work out of the Kotzebue region, to do the live captures and sampling that was common in past years, Wilson said.

“We haven’t been able to go out and do captures since 2017,” he said. And that spring, very rapid ice melt created a precarious situation. In a single day, the ice edge retreated 30 miles, causing the team to lose some of its supplies.

The project is an outgrowth of U.S.-Russian collaboration in 2012 and 2013 that surveyed Bering Sea seals, Conn said. Polar bears wound up as an add-on, he said.

Simultaneously surveying for ice seals and for polar bears was key to the project. At times, the thermal devices were not able to detect polar bears, Conn said, but they provided guidance to the bears’ locations by finding the seals that the bears were hunting, he said.

The relatively healthy seal populations in the Chukchi appear to be important to the polar bears’ ability to thrive despite declines in sea ice, according to recent research led by Karyn Rode of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Other polar bear populations are not faring as well as the Chukchi population. The Southern Beaufort Sea provides a striking contrast; both the total number of bears in the population and the body condition of those bears have declined significantly since the early 2000s, according to USGS research.

Some striking differences in habitat likely explain the divergence between Chukchi and Southern Beaufort Sea population conditions, Wilson said.

The Beaufort Sea has a narrow continental shelf that drops off into deep water where polar bears are unlikely to find food after the ice has retreated. But the Chukchi has a highly productive marine ecosystem almost entirely underlain by the continental shelf, giving seals and the polar bears that hunt them better opportunities to find food even when ice is diminished, he said.

That Chukchi advantage is expected to lessen over time as sea ice continues to diminish, Wilson said.

“I think everybody is pretty much in agreement that this can’t go on forever,” he said. “Eventually there has to be a tipping point.”

The U.S. and Russian agencies are not the only entities developing new technologies for monitoring polar bears from a distance.

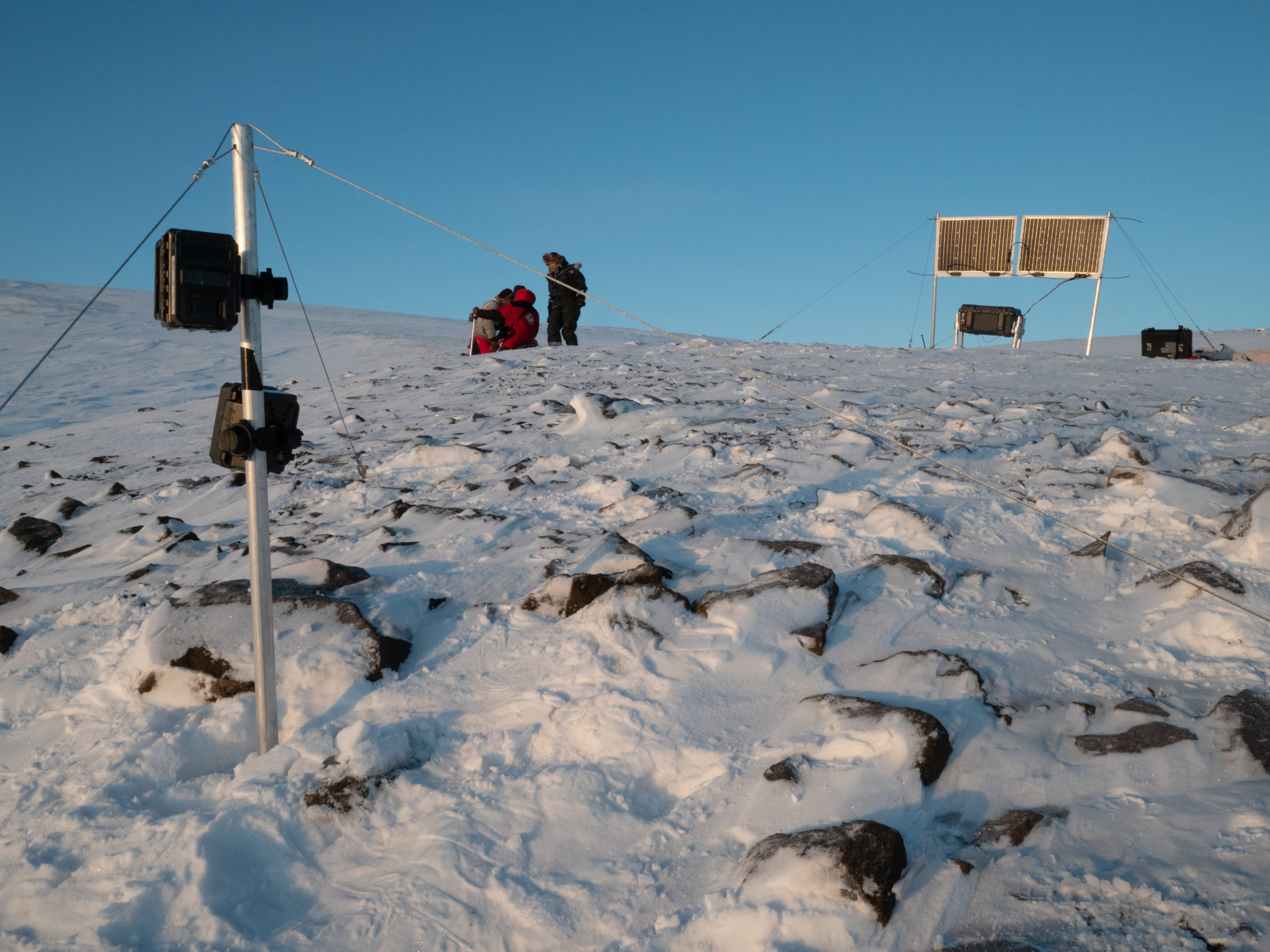

The nonprofit organization Polar Bears International is developing a system of solar-powered remote cameras to capture images of bears around dens. The system, with lightweight, energy-efficient computers and software being designed by the San Diego Zoo, is intended as a big improvement over remote cameras that require battery changes every few days.

Polar Bears International researchers were able to set up its solar-powered cameras last year in Svalbard just before the coronavirus pandemic shut down field research. The trial run did capture images of a maternal polar bear emerging from a den, said B.J. Kirschhoffer, the organization’s director of field operations.

That was a significant success for a field program that had to be conducted quickly and, ultimately, largely without the presence of scientists nearby, Kirschhoffer said.

“Of course, finding polar bear dens is extremely difficult, even if you know where their habitat is,” he said.

The project, a cooperative effort of Polar Bears International, the Norwegian Polar Institute and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, seeks to make use of solar energy when it is available and record movements of bears around dens — without the need for people to be present to tend to the camera systems.

“Our hope is that it truly does become a very simple research tool to help us better understand the world around us,” Kirschhoffer said.