The Bering Sea is already nearly ice-free, setting up more havoc for its ecosystem and residents

For the second year in a row, Bering Sea ice has undergone a dramatic mid-winter melt.

A year ago, a midwinter meltdown erased most of the ice in the Bering Sea, leaving vast stretches of open water and creating shocking conditions like storm surges in coastal villages normally protected by solid sea ice. The winter ice extent, when it hit its maximum last March, was the lowest, by far, in more than 150 years of records.

A similar scenario is unfolding this year.

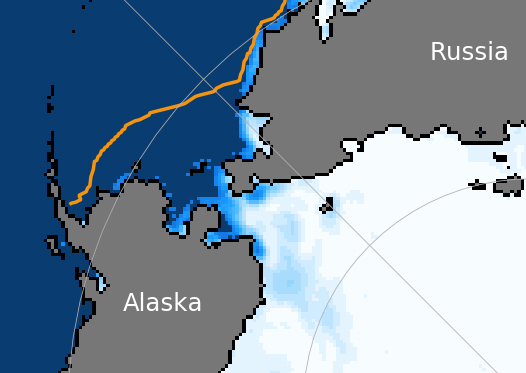

Since late January, the Bering Sea has lost two-thirds of its ice area, according to statistics from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Waters are open across the entire sea, including in the Bering Strait that separates Alaska and Russia. In the middle of that narrow strait, ice that normally links Alaska’s Little Diomede Island to Russia’s Big Diomede Island through May was gone by the end of February. “As of yesterday, between the islands there was no more ice at all,” Robert Soolook, a Diomede tribal leader, said on Friday.

Suomi NPP image courtesy @uafgina early Thursday afternoon, February 28. The loss of #seaice in the Bering and southern Chukchi Seas is beyond belief. The impacts to western Alaskan communities immense. #akwx #Arctic @Climatologist49 @IARC_Alaska @SNAPandACCAP @amy_holman @ZLabe pic.twitter.com/72DK19eLs2

— Rick Thoman (@AlaskaWx) February 28, 2019

As happened last winter, wind-driven waves have crashed onto beaches in places like St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Strait and in Kotlik, a mainland village of about 600 people that was flooded in mid-February. The open-water conditions extended north of the Bering Strait into the southern Chukchi Sea, off Shishmaref and Kotzebue. And at the start of March, the region’s ice area and extent was expected to keep dwindling, as unusually warm weather was forecast for the coming week.

With only about three weeks until the spring equinox, it appears that this winter’s Bering Sea ice maximum was set and passed in late January — an uncommonly early time for peak ice — and will be the region’s second-lowest maximum extent on record.

“For the raw extent, it’s not as bad as last year, but it’s worse than every other year,” said Rick Thoman, climate specialist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

That means a continuation of the warm-water effects that have scrambled the Bering Sea marine ecosystem, Thoman said. “With this very low ice, this guarantees a warm Bering Sea this summer,” he said. “The sea looks like a classic positive feedback.”

Among the effects was the lack of a “cold pool” of water, defined as colder than 2 degrees Celsius, that normally develops deep in the Bering Sea as top-layer water freezes and drops off salt. The cold pool separates northern and southern Bering Sea species and was considered a biological fixture until last year, when it failed to develop.

Was the ice that formed up earlier this winter but quickly melted enough to regenerate the cold pool in 2019? “I wouldn’t think so, but we’ll have to find out,” Thoman said. “I think this summer is really going to be a big eye-opener.”

Austin Ahmasuk, marine advocate for the Nome-based nonprofit Kawerak Inc., is also trying to figure out what this winter’s low ice — on top of last winter’s low ice — means for the future. “I think this is the beginning of the transition of the northern Bering Sea,” he said.

For now, the open-water conditions are creating some dicey conditions for people carrying out their day-to-day activities in the region.

In Nome, residents are able to use a limited mantle of shorefast ice to support their winter ice fishing, but “it is dramatically reduced,” Ahmasuk said.

In Wales, the mainland village closest to the Russian mainland, there was also enough shorefast ice to support some ice fishing, but that ice is vulnerable, said resident Robert Tokeinna. Winds and waves earlier in the week battered the shore, “So a lot of the ice just crumbled up and broke,” he said. Ice travelers need to be careful, he said. “You could probably go out with a snowmachine. But I wouldn’t put a truck on it,” he said.

Even the famous Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race is adjusting its operations because of the lack of sea ice.

The race, which has a ceremonial start on Saturday in Anchorage, has rerouted a portion of trail that normally crosses frozen Norton Sound on the approach to the Nome. Instead of mushing across the ice, teams will stick to land and go around the sound.

“It may be a little longer. It may be a little hillier,” said four-time champion Martin Buser.