Climate change is driving the North Water Polynya toward collapse, study finds

A new study finds the critically important area of open water between Greenland and Canada — known to Inuit as Pikialasorsuaq — is changing with "unprecedented speed."

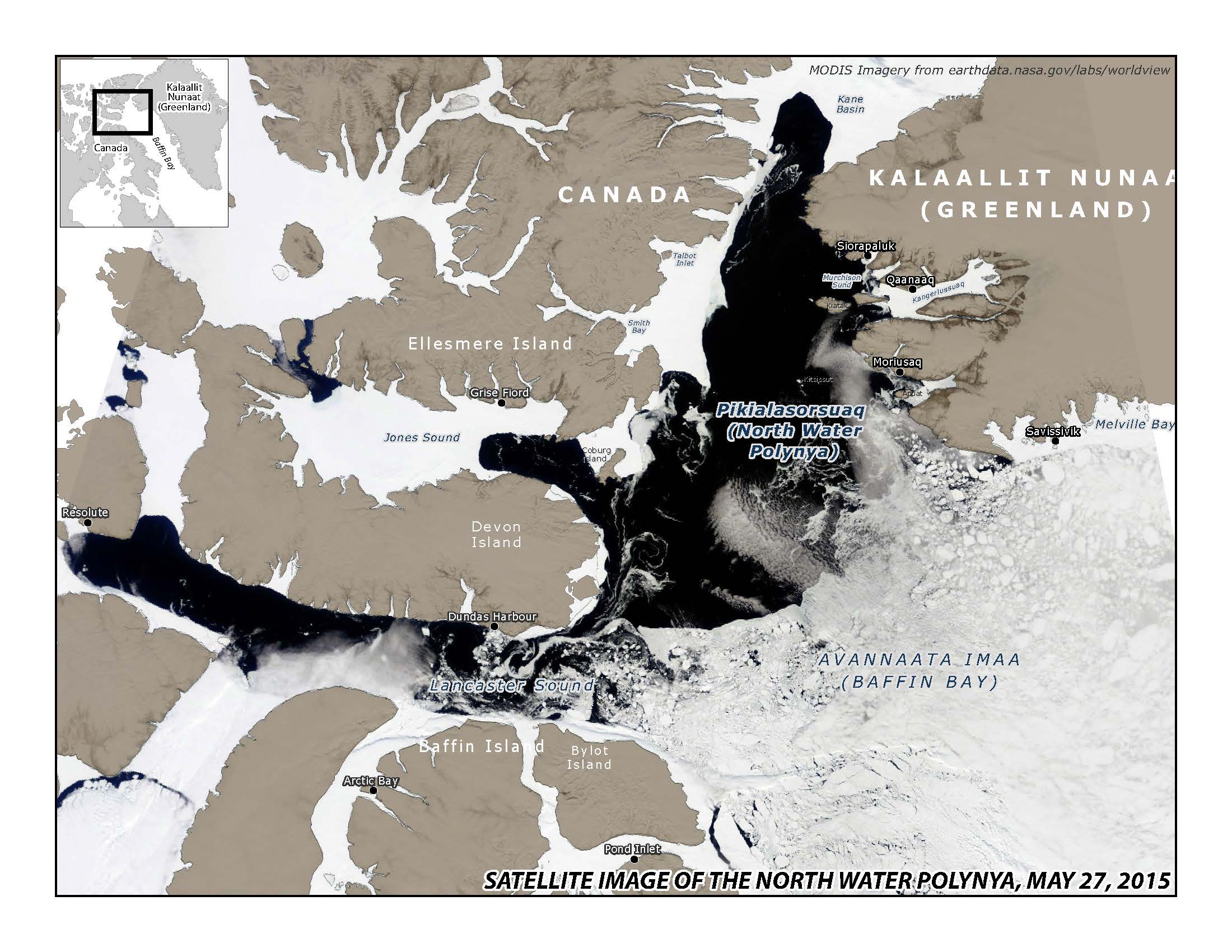

The North Water Polynya, known to Inuit as Pikialasorsuaq, is an area of year-round open water wedged between Greenland and Canada’s Ellesmere and Devon islands, and it’s a hotspot of biological productivity.

About 2,000 years ago, the polynya collapsed when a period of warming sent chunks of pack ice into it during spring and summer, filling it with ice and disrupting the patterns that make it so important to people and wildlife.

Now the polynya is heading toward another collapse — this time driven by human-caused climate warming, concludes a new study published in Nature Communications.

The “unprecedented speed” of changes, the study warns, poses serious threats to Indigenous people who depend on wild food harvested from the North Water Polynya, (abbreviated by scientists as “NOW”).

[The plug keeping the Arctic’s oldest ice in place is getting leaky]

“On our present climate trajectory, the NOW will likely cease to exist as a globally unique ice-bounded open-water ecosystem, and a winter refuge for keystone High Arctic species,” the study says. “The vulnerability of the NOW is a clear example of the emerging climate change risk associated with changing sea ice conditions on the productivity of indigenously harvested resources.”

The polynya holds a blend of warm water from the Atlantic, cold Pacific water transported through the Northwest Passage and ice and glacier melt, all of it moved by currents and winds. A solid ice bridge is what has kept it protected from ice chunks that might float down from higher Arctic waters. An upwelling of warm water is what keeps it open and helps make it one of the world’s most biologically productive regions above the Arctic Circle. Indeed, the Inuit name Pikialasorsuaq means “great upwelling.”

The Nature Communications study, by an international team of scientists, traces the polynya’s past ups and downs through the diatoms and chemical fingerprints in the region’s marine and lake sediments. One bird species, the little auk, is used as a marker of polynya health.

Little auks now number about 33 million in the North Water Polynya area and are considered critical to the ecosystem there. But the species declined dramatically starting about 2,700 years ago and virtually disappeared about 2,200 years ago, the study found through its sediment analysis. That corresponds with human abandonment of the area. There was “a long-term void in the human prehistory of Greenland,” overlapping a time of climate instability, which veered from the Roman Warm Period to the Dark Ages Cold Period, the study notes. The little auk population recovered about 800 years ago, the study found.

Before the collapse of the polynya, the area was inhabited by pre-Inuit groups, and after the gap that is marked by the absence of little auks, Greenland was settled by the Thule Inuit, said Sofia Ribeiro of the Geological Survey of Greenland and Denmark.

[Why the lingering dispute between Denmark and Canada over a high Arctic island is so important]

The imminent new threat to the icy habitat that surrounds the polynya has been clearly documented, Ribeiro said by email.

Two signs of instability can be readily witnessed through satellite observations, she said. “One is that the ice arches are breaking up earlier than they used to, due to sea ice being thinner and warming temperatures, and the other is that they are failing to form at all some years. This was first observed in 2007 and has occurred several times since, indicating that it will become the ‘new normal,’” she said by email.

Though an expanded area of open water might bring more biological productivity through more widespread phytoplankton blooms, it would also negate the physical characteristics that make the polynya such a special biological oasis, Ribeiro said.

A key to the polynya’s productivity is the “active mixing of deep waters that are rich in nutrients with the surface waters,” she said. “This happens due to active sea ice formation and winds. If the surrounding sea ice goes away, we get less mixing and the surface waters become fresher and poor in nutrients, so less productive.”

The Pikialasorsuaq Commission, a joint Greenlandic-Canadian Indigenous organization, was created in 2016 to study ways to better protect the polynya.