In Iceland, a disagreement over how best to protect a natural treasure

Even proponents of a long-discussed proposal to create Europe’s largest national park in admit it may need to be created in phases.

Iceland’s highlands, according to a website promoting creation of national park there, is one of that country’s greatest treasures. It’s a statement few would disagree with.

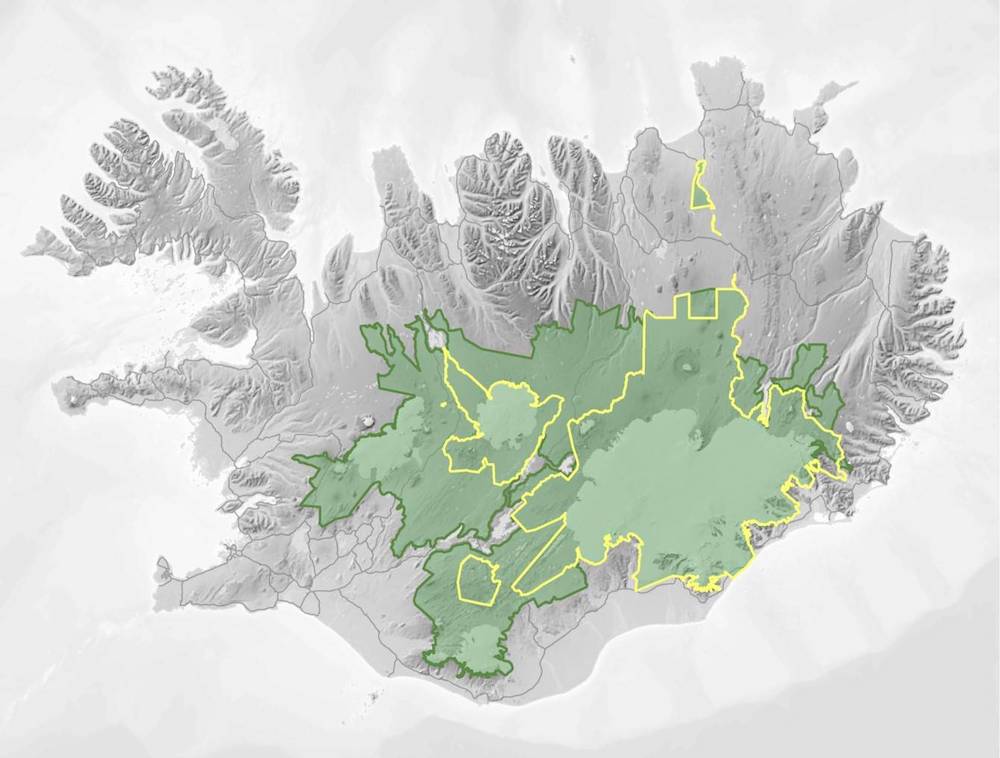

Repeated polls have shown there is widespread support for establishment of Hálendið, which would encompass about a third of the country’s entire area and be Europe’s largest national park. Academic research conducted by Michaël Bishop as part of a University of Iceland master’s thesis published this summer, found that just 10 percent of residents are opposed to the idea.

Those who do not support creation of a national park say it is not a matter of not wanting to protect the vast tract, which includes glaciers, volcanoes, waterfalls and much else that Iceland is renowned for. Instead, says Tryggvi Felixson, the chair of Landvernd, one of the environmental groups working to establish the park, they feel that the treasure is one that should be there for the using: all of the land it would encompass is already public land that for ages has been used for sheep grazing; more recently it has become a popular destination for visitors, many of whom pay to be taken there. A redesignation would probably place limits on both types of activities.

Despite the success of Iceland’s three existing national parks, support for the types of regulations that would be needed to create Hálendið generally does not go down well with Icelanders.

Access rights, according to Bishop’s work, are believed to contribute to the quality of life of residents and are linked to the culture and identity of the population.

“Therefore,” he says, “access management in protected areas is not well accepted, as it is perceived to be incompatible with this public right.”

Perhaps, then, that is partly why lawmakers have expressed reservations about passing a bill that was introduced in Alþingi, the national assembly, earlier this month. The project, which has been in the works since 2015, is a key goal for the government of Katrín Jakobsdóttir.

[In Iceland, a canyon’s closure provides calm after storm of unexpected fame]

But even though a pledge to establish a national park is written into the 2017 manifesto agreed on by the three-party coalition, two of the parties expressed reservations about establishing the park as it was presented, arguing that it runs roughshod over the rights of local governments to decide over how the land is used, which, in addition to limiting things like grazing and tourism, would probably also put hydroelectric power generation there out of the question.

Critics of their argument note, however, that only 3 percent of Iceland’s population live in municipalities that would have land inside the national park. Allowing their arguments to hold up establishment of something most people want, is unfair, they say.

Besides, they point out, the proposal calls for the creation of a body that would include representation from groups that currently use the land and would make decisions about what activities are permitted and where.

[Iceland unveils a memorial plaque for the first glacier it has lost]

Felixson is uncertain that, even if some sort of compromise can be found, a piece of land the size of Hálendið can be made into a national park all at once.

“Maybe this is just too big for Iceland to swallow,” he says.

Size, though, need not be a barrier. One of the country’s other national parks, encompassing the Vatnajökull glacier, was formed in 2008 when two existing national parks were merged and new land was added. Since then, its boundaries have expanded further. Applying a similar strategy to Hálendið may allow national lawmakers to acknowledge local opposition without having to drop the effort entirely, he reckons.

The 28 or so groups that are officially pushing for the establishment of Hálendið include tourism groups. Supporters are primarily interested in conservation and managing tourism.

The concerns expressed by the opposition revolve around the reduction of opportunities for outdoor recreation, the operational cost of the park and governance issues.

“Securing a broader support for its establishment relies on the ability to meet expectations of supporters while addressing concerns of the opposition,” Bishop says.

Felixson expects that changes to the park as pitched earlier this month will probably be necessary. He says he is willing to compromise, particularly if the alternative is scrapping the plan entirely.

“We are mostly likely not going to get this national park,” he says, “but the whole idea of a natural park is to protect nature and make it accessible. The worst outcome for everyone would be no decision at all.”

Correction: This article originally stated that 86 percent of the land making up the proposed Hálendið national park is existing public lands. We are appreciative to Michaël Bishop for making us aware of the changes to the legislation, as well for providing us with a map of the park’s boundaries, which replaces a map we included showing the extent of public lands in the Icelandic highlands.

Additional grammatical changes have been made to delineate better between the results of Bishop’s research and the input we received from other sources.