How a legal dispute over coat could be a turning point for Arctic Indigenous peoples’ intellectual property rights

The lawsuit might be the first to make an infringement claim based on a traditional Indigenous design.

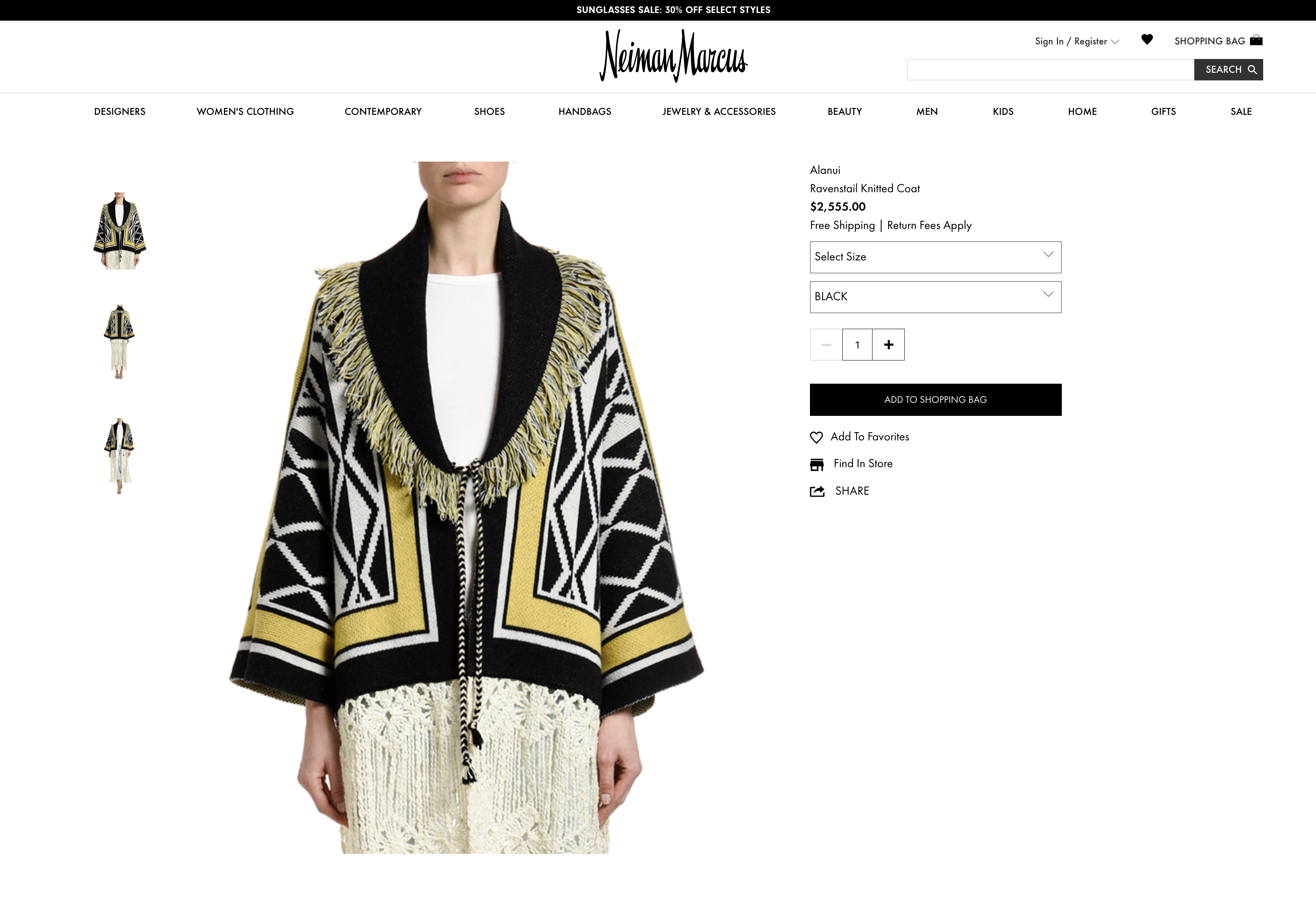

A $2,555 knitted coat sold by Neiman-Marcus has sparked a copyright lawsuit that might set a new standard for Indigenous intellectual property.

The retailer’s “Ravenstail” coat appropriates both the name and the design type that are part of Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian culture, according to a federal lawsuit filed by the Juneau-based Sealaska Heritage Institute.

The coat itself is a near copy of a specific Ravenstail robe created in 1996 by the late Clarissa Rizal, a Tlingit artist who was named a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment of the Arts, says the lawsuit, filed on April 20 in U.S. District Court in Juneau. Rizal’s heirs now hold the copyright to the robe, titled “Discovering the Angles of an Electrified Heart,” and they have licensed it to the Sealaska Heritage Institute.

“In our opinion, this retail garment looks like a Ravenstail robe, and it features a replica of a design that is protected by copyright. It’s one of the most blatant examples of cultural appropriation and copyright infringement that I’ve ever seen,” Rosita Worl, president of the institute, said in a statement.

The lawsuit appears to be the first to make a claim based on a traditional Indigenous design, said Jacob Adams, one of the attorneys representing the Sealaska Heritage Institute in the case. The lawsuit alleges violations of copyright law and violations of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

Other complaints filed in the past that used the Indian Arts and Crafts Act were generally focused on Native names, including actual tribal names, Adams said. The part of the lawsuit that cites the use of the Ravenstail name does, in some ways, parallel past cases concerning Native arts, he said. But what is new are the copyright claims about the traditional Ravenstail weaving pattern, he said.

Neiman Marcus failed to respond to complaints sent from Alaskans in customer comments, according to the lawsuit, and neither Neiman Marcus nor its affiliated online retailer, My Theresa, have pulled the item from sale.

As of April 28, Neiman Marcus had not responded in court to the Sealaska Heritage Institute’s lawsuit or responded to inquiries from ArcticToday.

The dispute over the Ravenstail coat is a recent example of a problem that has persisted for generations, Adams said. “Rights of Indigenous groups to their cultural resources are often ignored,” he said. “These rights are there. We just have to have more recognition of them.”

Efforts to combat violations also go back generations.

The United States is fortunate to have a longstanding law on the matter that has some teeth, Adams said. The original version of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act was enacted in the 1930s, though no one sued under it prior to the 1990s, he said. Even in the 1920s, when the law was first being discussed, concerns about protecting Native artists were similar to what they are now.

The law also protects non-Native consumers, he said. In the Neiman Marcus case, the coat’s name, design and steep price tag could give the erroneous impression that it’s an authentic — and therefore valuable — piece of Alaska Native art, Adams said.

“If you sell a ‘Ravenstail’ coat, it calls up in the mind of the consumer, for us, that that is genuine, just as much as if you were to say it’s a Tlingit coast or a Haida coat,” he said.

In Canada, Indigenous groups have called for a national law similar to that in the U.S.

Inuit artists in Canada are protected by a trademark “Igloo” tag created in 1958 to protect indigenous artists from counterfeiting. The Inuit Art Foundation took ownership of that Igloo tag in 2017, giving it standing to sue over violations.

The idea of protecting Arctic indigenous intellectual property is getting more attention as the world focuses on ways to respond to the rapid warming of the Arctic environment. In one recent study, scholars from the University of Iceland and Elizabethtown College said the Arctic Council and other organizations should consider intellectual property as a parallel to the traditional knowledge that is important to understanding ecological systems.

“In that way, Arctic Indigenous peoples may help the emerging global society to place the same emphasis on maintaining cultural variability in the north that has already been emphasized for biological diversity,” said their paper, published in the 2017 Arctic Yearbook.

The World Intellectual Property Organization, a United Nations organization, has also been examining ways to better protect Arctic Indigenous culture from improper use.

For now, however, the legal protections amount to a patchwork, varying by location, Adams said.

Sometimes, issues have been addressed outside of courts.

After Walt Disney Studios upset Fennoscandia’s indigenous Sami community with what some considered an inaccurate and disrespectful portrayal of their culture in the animated 2013 movie “Frozen,” the studio worked with Sámi consultants to make improvements in the 2019 sequel. That was the result of an agreement between the studio and the Sámi Parliaments and the Saami Council. Adams, who spent about a decade working in Scandinavia, was helped negotiate the agreement.

In another recent case, Inuit artist and activist Tanya Tagaq won some concessions from a U.S. choir that used throat singing in one of its songs. The choir agreed to credit the Inuit culture and any other traditions with styles or techniques used in songs.