A convoy of private planes is making a friendship flight to link Alaska and Russia

Eleven pilots and passengers in six planes will fly a rarely used route between Nome, Alaska and Provideniya, Chukotka in hopes of keeping strong cross-border connections.

Three decades after the melting of the “Ice Curtain” that separated Alaska and Russia during the Cold War, a group of Alaska aviators is trying to shore up relationships across the Bering Strait.

A convoy of six private airplanes with 11 pilots and passengers was gathered in Nome for a brief trip to Provideniya in Russia’s Chukotka region.

The idea is to revive a transportation route that allows regular general aviation travel between Alaska and the bordering region of Russia, said Tandy Wallack, president of Anchorage-based Circumpolar Expeditions and one of the organizers.

“This is an effort to maintain the air route and to make sure it’s operational and keep it open,” Wallack said in an interview before the trip, which was scheduled to start June 23 but was on a weather hold as of Monday.

The less the route is traveled, the more difficult each trip becomes, she said. When there are only occasional flights, each requires loads of regulatory permission and paperwork — but that burden is lightened as the volume of traffic increases.

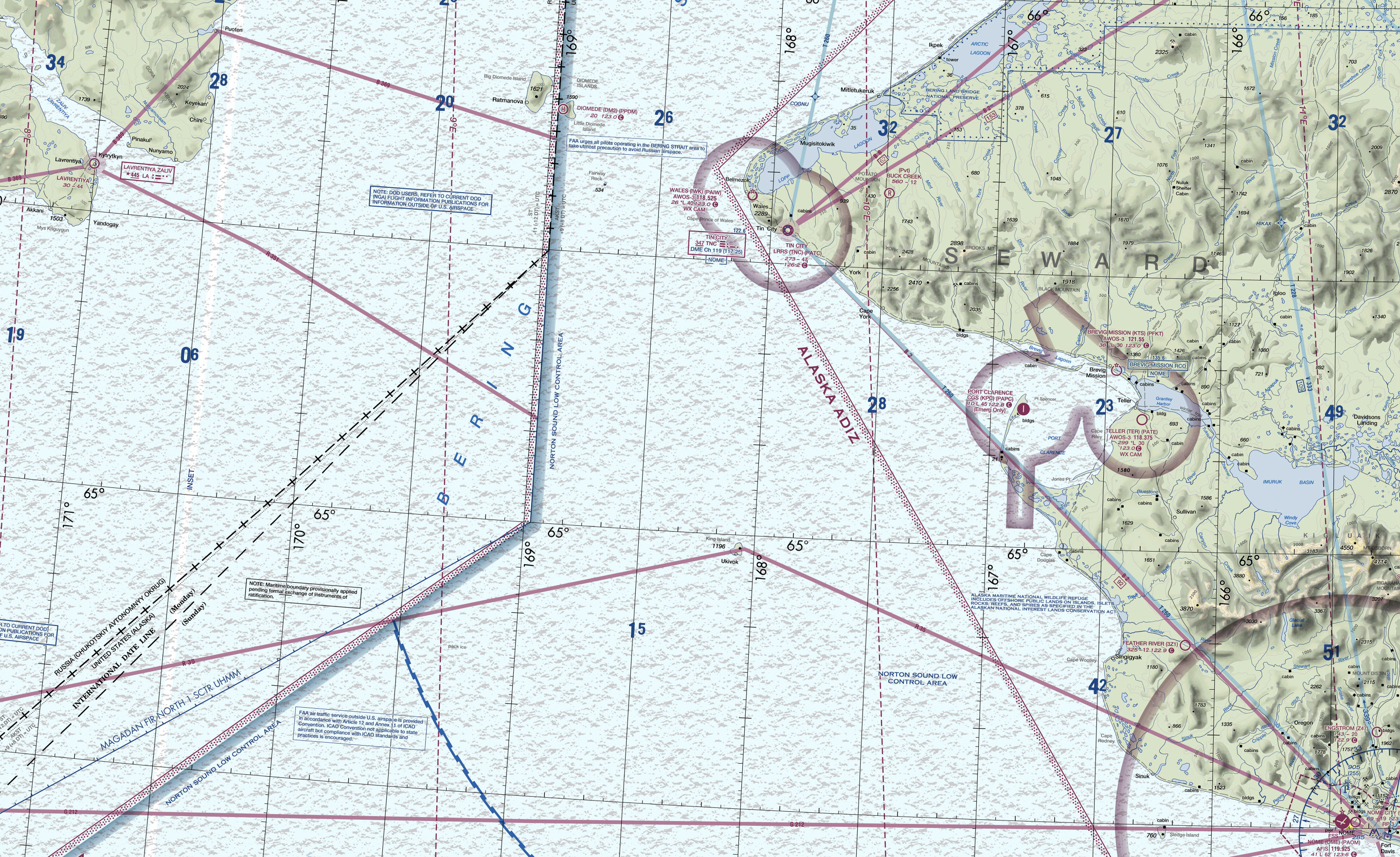

The 270 nautical miles between Nome and Provideniya, a distance that takes a mere 50 minutes to fly, has a special designation from the Federal Aviation Administration: B-369. There are several rules for use of the route.

During the Cold War, that short trip was considered a no-pass zone. But the route was opened in the era of glasnost, thanks to efforts of regional governments and citizens on both sides of the Bering Strait.

An inaugural jet trip, the 1988 Friendship Flight, took a large Alaska delegation to Provideniya. Aboard the special Alaska Airlines flight were then-Gov. Steve Cowper, business leaders and Alaska Natives who were reuniting with Siberian Yupik relatives on the other side of the international border.

The Friendship Flight was a breakthrough in international relations, and its significance is examined in a book, Melting the Ice Curtain, by David Ramseur, who was Cowper’s press secretary and a member of the delegation.

For a while, the route across the Bering Strait was buzzing with activity.

In the early 2000s, there were numerous economic trips, tourist expeditions, cultural exchanges and personal flights, Wallack said. But as U.S.-Russia relations cooled, so did the flight traffic.

Now private pilots are in a situation when they have to use the route or lose it, she said, “If you don’t keep using it, then it’s not operational anymore,” she said.

The current six-plane flight is something of a revived version of the 1988 Friendship Flight, she said.

Concerns about the Nome-to-Provideniya route falling into disuse have been mounting in past years. Two of the organizers of the current expedition, Dan Billiman and Marshall Severson, made a similar flight in 2017 with the same goal, but with just a single plane.

Wallack has a lot of experience traveling the Russian Far East. Her company has been ferrying tourist groups to the region, and it has done much more than mere sightseeing. With help from the U.S. Agency for International Development and the National Park Service, Wallack was able to conduct a training program that taught local Chukotka people to work in various aspects of the tourism business. Now when she brings groups to the region, the Chukotka locals provide apartment space for lodging and serve meals at school with a culinary program. Young Chukotka people also take part in the tours by working as guides, a gig that allows them to practice English.

Such activities are important to ensure that relations across the Bering Strait remain friendly, whatever problems may be happening at the higher levels of government, Wallack said.

“That’s the kind of connection we need to maintain. It’s people-to-people,” she said.

Wallack has ambitions beyond strengthening of Nome-to-Provideniya travel. She wants to extend the route to Anadyr, a bigger city than Provideniya and the administrative seat of the Chukotka region. She also wants to travel to Big Diomede, the Russian island in the middle of the Bering Strait that is only about 2.5 miles from Alaska’s Little Diomede. She would like to see the Russian government establish in the Chukotka region the same kind of 72-hour visa-free travel that is allowed for people coming from Helsinki to St. Petersburg.

There is a lot of desire for travel from Alaska to these areas in Russia, Wallack said. “I like to tell people that the Arctic is hot right now,” she said.